Pulldowns: The What, Why, and When

Though controversial pulldowns are a staple of our off-season program, we see them as vital pieces to train athletes to handle the stresses of pitching. But, like everything, they can be misunderstood when not done in the proper context.

The What

Pulldowns, otherwise known as Running Throws, Crow Hop throws, or Run ‘n Guns, are max-effort throws with a running start thrown in the off-season.

At Driveline, we have athletes throw pulldowns once a week, in the offseason, in a standard progression using 3–7-oz weighted baseballs.

The history of pulldowns comes from long toss. As part of Alan Jaeger’s long-toss routine, athletes would throw extension throws out to a certain distance. Then, depending on the day and schedule, as the two players got closer to one another, they would pulldown, throwing max effort on-a-line.

So, on high-effort days, athletes would long-toss throwing light and high-arcing throws out (extension phase), followed by harder on-a-line throws when coming in.

We adapted this as a part of our program and simply added a radar gun, so we can track velocities. The correlation between velocities of the balls varies but they top out at an R^2 of .7 between a 5-oz running throw and max-effort pitching on a mound.

We know that correlation doesn’t equal causation, but athletes that throw faster pulldowns see higher mound velocities.

The Why

The reason comes down to two things: intent and stress.

We see the intent to throw hard as a key characteristic that athletes should try to develop in the off-season, because it is often overlooked.

We know that intent can mean a variety of things, but in regards to pulldowns, we are looking for the intent to throw hard. Pitchers are often coached in a manner that involves being overwhelmed with cues and trying to think of where their body is in space all while moving at incredibly fast speeds.

This is often not balanced by athletes’ focusing on throwing hard.

Focusing on throwing with intent can work wonders for some athletes, and you can look to Charlie Morton as a recent MLB example of having success after trying to throw harder. But even if throwing at max effort doesn’t yield in the best results, athletes will know they can do it, and it gives them a better filter for the effort they’re are throwing at.

Some athletes very well may sequence better while trying to throw at an 90 or 95 percentage effort, (a percentage that is uniquely individual to each pitcher) but how does a pitcher actually know what his 90-95 percentage effort is if he’s never thrown at 100% effort?

The other reason pulldowns are so important relates to stress levels, mainly the fact that we want to try and push athletes to meet or go slightly past their strength levels seen in games.

The good news is that there is both peer-reviewed (3rd party) and our own (1st party) research that supports the idea that pulldowns are equal to or less stressful than pitching.

ASMI found “statistically insignificant” differences between pitching a 5-oz ball and crow hopping a 5-oz ball. They also found that the heavier balls (6- and 7-oz) resulted in less elbow and shoulder torque when compared to a baseball.

We replicated the ASMI study by looking at 5-oz throws with the Motus sleeve and found similar results. We also looked at the stress of throwing 3-7 oz balls during pulldowns and found little no statistical difference between the balls.

So pulldowns do replicate or slightly exceed pitching stress, but why is that good?

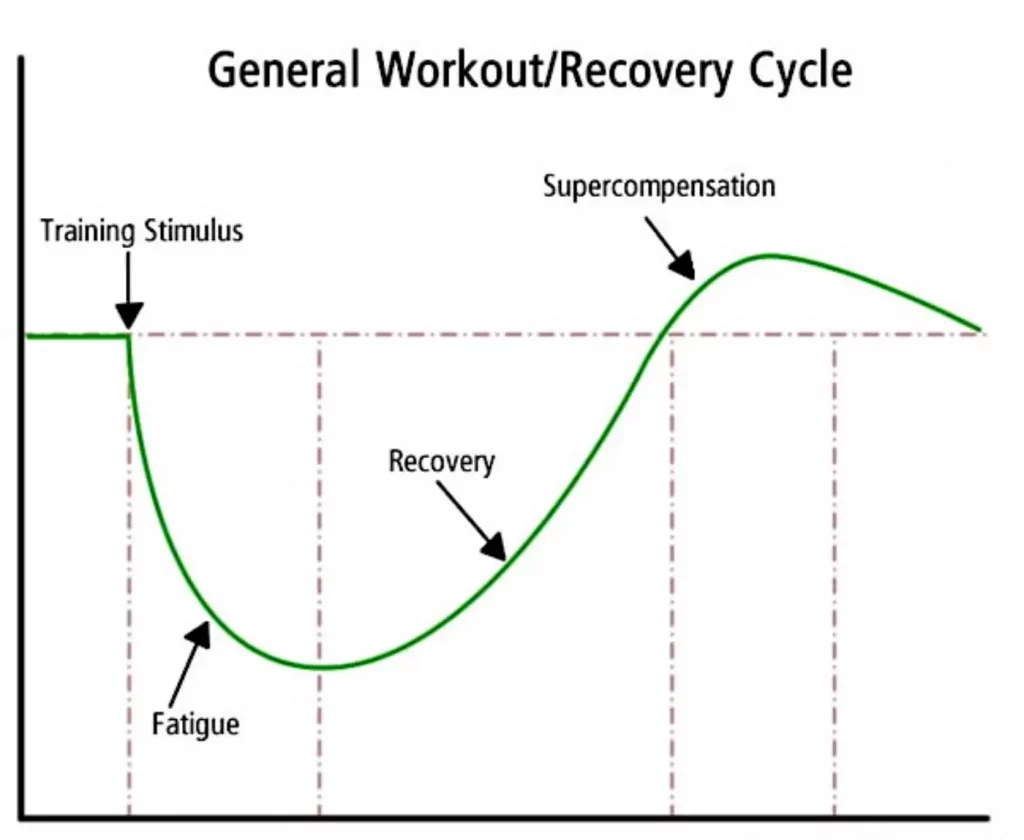

Think of the supercompensation effect from the body’s stress-response cycle.

You need a stimulus that will push the body to adapt to higher velocities. Many athletes do not receive this stimulus but still expect to throw harder.

Let’s use an example of an athlete and focus on the assumption that the harder an athlete throws, the more stress he is occuring on his arm. There, of course is nuance to this idea, but let’s still narrow in on that idea. A pitcher, when compared to himself, is going to be experiencing higher elbow stresses when his velocity increases.

So now let’s use an example of a college pitcher, say a junior at a D1 school. Throughout the year, this pitcher is going to throw a number of bullpens and live-simulated games in the fall and winter. Many of these, for a number of reasons, are not going to be tracked for velocity.

Let’s say this is a good starter who can top out at 90 mph on a good day, but usually sits between 86-89 mph.

All throughout fall and in scrimmages, this athlete is able to maintain his velocity in the 86-89 mph range. But come winter school, with unmeasured bullpens and other factors (school, sleep, etc.) contributing, he unknowingly finds himself throwing many of his bullpens (with a focus on command and offspeed pitches) somewhere between 82-86 mph. Remember, these bullpens aren’t tracked for velocity so neither the player nor coach knows this.

Because of this, this pitcher spends the next 2-3 months throwing bullpens between 82-86 mph. On bad days when he’s tired from school and up at 5 a.m. he’s even slower, while on days he’s feeling good, he’s closer to game speed.

All of a sudden spring is upon the team, and this player is ready to throw. He’s been told he is starting the second game of the year, is super amped up for the opportunity, the umpire says play ball, and his first pitch is 90 mph.

Now, understanding what we said earlier, that we’re making the assumption that stress is increasing with velocity, what about throwing offseason bullpens at 82-86 mph prepared this pitcher for his first outside pitch of the year at 90 mph?

Nothing really, which doesn’t do much for an athlete from a preparation view. If this pitcher sits at 86-90 mph for the entirely of the game, there is good chance that the majority of his pitches are being thrown at stress levels that he hasn’t experienced in months.

Alternatively when you see athletes lose velocity and there isn’t an injury, there is a decent chance that it’s because they’ve simply been training at lower intensities for longer periods of time. Though this can be unusual, we would see this as undertraining, which is why we want to schedule pulldowns at specific times to max or push past in-game stress levels.

Now, before you start worrying about training and feel like you need to get your athletes throwing at high intent all the time, understand then when using pulldowns, they should never occur outside of a detailed schedule to meet your goals. Pulldowns work because they are tracked for velocity and only thrown on a schedule.

The When

I’m going to repeat that last part again because of its importance:

Never throw pulldowns outside of a detailed training schedule designed to meet an athlete’s goals.

If you wouldn’t have pitchers throw a bullpen on a random day, then you shouldn’t have them pulldown on a random day. Everything else you do in your training needs to be in-line before doing high-intent work.

This is the big picture that leads to the largest misconceptions about pulldowns: that you can or should do then whenever you want.

Many don’t understand that the only way for pulldowns to be effective is when they are a piece of a detailed training program. One doesn’t (or shouldn’t) exist without the other.

We see pulldowns as a key component to building velocity and intent, but all athletes need to have their mobility, strength, and arm care work as a solid foundation first.

Discussions of scheduling are also linked to workload monitoring. We want to be able to increase an athlete’s workload and throwing tolerance to a level of max-intent throwing. We do not want to assume that since they’re taken time off, they are immediately ready to throw at high intent. This goes for both pulldowns and bullpens.

If a long time off from throwing is unavoidable, we recommend a longer on-ramp, such as our return-to-throwing program.

If you have athletes throwing a baseball regularly for a few weeks, you can slightly shorten the on-ramp phase, while doing PlyoCare ® throws for a few weeks to ramp up to high intensity throwing.

In either case, you need weeks of low-intent throwing to prepare yourself for high-intent work.

The best time for pulldowns is the fall or early winter, But it also depends on what the athlete’s goals are and his timetable.

When planning out a throwing schedule, take into account how much an athlete has thrown (and how much time off they’ve had) along with how much they are expected to throw in the next few months.

Regardless of the time of year, athletes need to take the time to work up to an intense workload.

Below is an example schedule of when athletes can expect to throw pulldowns.

Late Fall: Velocity building (pulldowns)

Winter: Velocity building (pulldowns/mound velos) / transition to mound work

Spring: Competitive season

Early Summer: Competitive season or training

Late Summer / Early Fall: Time off

You can also individualize programming depending on what your players needs are, by having athletes do velocity specific work for different periods of time.

Athletes need time to work up, and even though pulldowns can be fun, you need to take the time to properly on-ramp. Also, take into consideration the amount of throwing players have done in the last year to individualize training accordingly. Schedule backwards, start from game one of the season and work back.

Wrap Up

Pulldowns are a key piece of building intent, developing velocity, and helping pitchers become more athletic. But they are still just a piece, they aren’t the whole picture. It comes down to scheduling and looking at everything your athletes are doing to get better.

This article was written by Research Associate Michael O’Connell

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

dbiz4 -

Awesome stuff. I have my 15u pitchers doing plyo’s, bands, recovery (pretty much everything) and we have been killing it! Thank you guys for every thing y’all do and keep being dudes! -Drew