How to Pitch Faster: Using Rotational Lateral Bounds to Improve Pelvic Loading

The lateral bound, also called the lateral skater jump or lateral heiden (named after former Olympic speed skater Eric Heiden) is a fantastic frontal plane lower body exercise. It gets athletes out of constantly training in the sagittal plane, and has shown a high correlation to ball velocity when compared to other measures of lower body strength and power, such as medball scoop and squat tosses, unilateral and bilateral vertical jumps, single / triple broad jumps and 10 / 60 yd sprint times (Lehman et al., 2013).

However, we know that pitching is a motor pattern that relies on not just drive leg hip abduction, and hip/knee flexion/extension, but also a significant rotational component as well. The traditional lateral bound only trains the leg musculature in the sagittal and frontal planes, neglecting the transverse (rotational) component.

Furthermore, many young athletes have never fully understood what the pelvic loading/unloading process feels like when attempting to throw faster. Many mistakenly think that it is a purely frontal plane “push” when the reality is that high level throwers create torque via their hip rotator muscles, holding this tension as they drive towards the target, before releasing it into a late, smooth and powerful opening of the hips into landing.

Let’s take a look at the traditional lateral bound (pause the video and hold down on the video buffering bar to scroll frame by frame)

Here is the rotational lateral bound, which involves creating a torque at the hip joint (i.e. pelvic loading) followed by an explosive unloading of this tension (i.e. pelvic unloading). Whereas the countermovement in the lateral bound is a drop into knee/hip flexion and hip adduction (followed by the opposing movements – extension and abduction), the countermovement in this exercise is a combination of those same factors, but also adding in a stretch of the hip rotators, which drives the hip unloading process, crucial to converting linear back leg drive into usable rotational kinetic energy and for achieving a biomechanically efficient position at landing (front leg braced, hips open, back foot turned down and over).

And finally a standard throw with a Plyo Ball ® (note the similarities in the lower half, even at just a 30% throw)

For comparison, let’s check out a couple hard-throwing big leaguers….

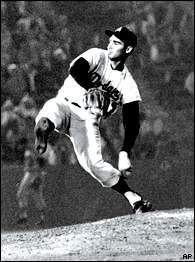

Notice how the back leg drives into aggressive hip abduction and hip extension, while HOLDING this hip internally rotated “knee pinched” position. An indication that this process is occurring properly is when the back foot begins to invert, with the majority of the pitcher’s bodyweight being held on the inside (medial) portion of the back foot. The center of mass begins to move directly towards the target while the upper body stays back and shoulders stay closed.

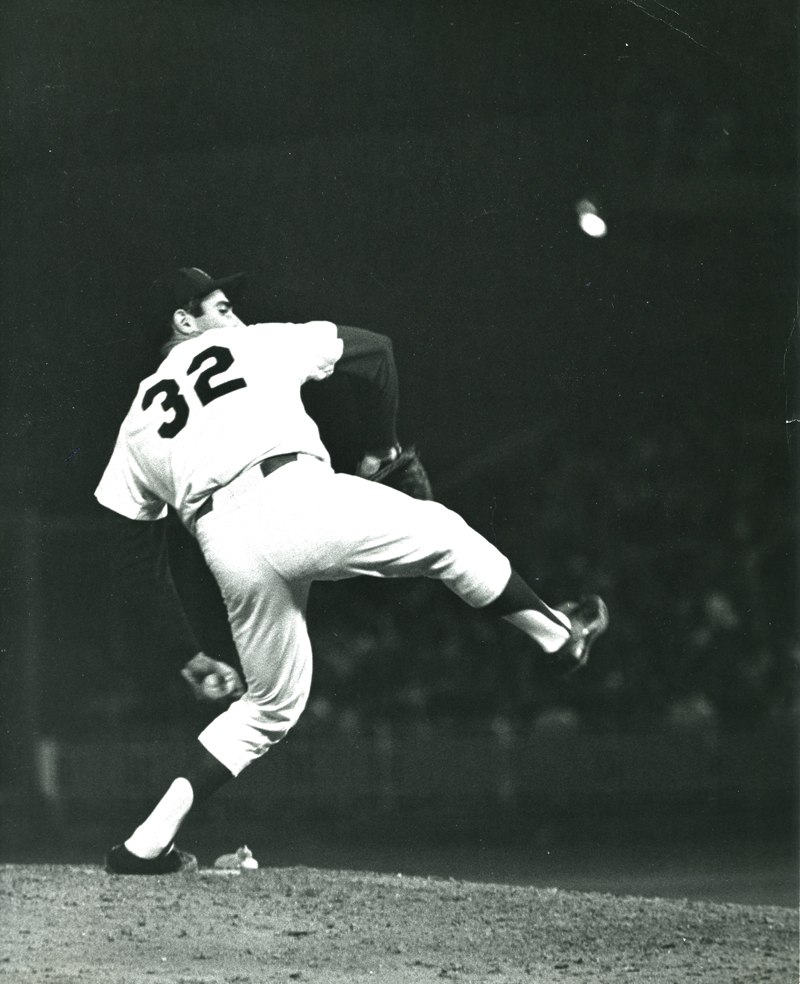

In addition to Aroldis Chapman, Sandy Koufax is one of the most obvious examples of this pelvic loading, holding a ton of internal rotation torque in his back hip joint as he drives his center of mass towards the plate (via hip abduction and extension), keeping his upper body back and shoulders closed. Watch 0:45 in the following clip to see what this looks like.

Sandy Koufax – creating an internal rotation torque at the back hip

Putting it all together

Maxing out the contribution of your lower half to your throwing motion is complex, but the fundamental principles are relatively simple – 1) learn to apply more force into the ground, 2) learn to apply that force in the right direction and 3) learn to sequence the segments properly and with good timing in order to facilitate maximum transfer of this energy into the later links of the kinetic chain.

Applying more force into the ground

- A balanced, periodized and individually designed strength and conditioning regimen that focuses on maximum eccentric, isometric and concentric force production, as well as rate of force production in the sagittal, frontal and transverse planes.

- Doing squats, cleans and deadlifts for 3×10 is simply inadequate to fulfill this need. For absolute novices, any strength work is going to work, but after a certain point the programming must shift to accommodate increased recovery demands, decreased rate of adaptation and lack of specificity (implementing triphasic and triplanar principles).

- For rotational lateral bounds, work them into your lower body training days, performing 3-6 sets of 3-5 reps on each leg prior to your main lifts of the day. It’s okay to continue rotating other xpxlyometricxx movements, but this is a good one to include in the mix.

Applying force in the right direction

- The pitching motion isn’t a vertical jump – it’s actually more of a lateral and rotational one. As such, we need to be able to produce large horizontal ground reaction forces while maintaining a rotational torque at the back hip joint during the driving phase to facilitate a fully rotational unloading of the hips into landing.

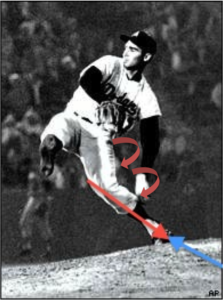

- The youth pitcher below applies force improperly into the ground. The red arrow is the direction of the force vector he is producing into the ground, while the blue arrow is the resulting ground reaction force of equal magnitude occurring in the opposite direction. The back foot is planted flat on the ground, there is no drive occurring through the center of mass and there is no rotational torque being applied in order to create usable rotational kinetic energy into landing.

- Sandy Koufax applies more horizontal force into the ground. In addition, he carries rotational torque in the hip joint, and actually unloads his hips into landing while propelling his center of mass explosively towards the target.

Learning to sequence the segments with good timing

- This is where repetition / deliberate practice comes in. You have to know what you’re trying to accomplish with every rep of every throw, whether it’s during long toss, flat grounds, bullpens, whatever. With time, you will learn what it feels like to be “connected” – certain throws will jump out of the hand with seemingly no effort in long toss or catch play. Chase that smooth, fluid, whip-like, connected feeling with every throw. Keep the arm rag loose from the elbow to fingertips. Experiment and see what cues produce the best results. Get to the point where your motion functions as one rotational, smooth and powerful unit. Repetition is the only way.

- Long toss is a great tool due to the immediate feedback – not just the distance of the throw, but the arc that the ball takes and the feeling of each throw out of the hand. Being able to see this immediate feedback is absolutely crucial to having productive throwing sessions – throwing into a net alone is generally not enough if major changes or refinements need to be made to a pitcher’s delivery.

You now have some tools and information at your disposal to start developing elite lower body mechanics. Keep in mind that effective lower body mechanics are just one piece of a well-synced throwing motion that produces high velocities safely. For more information on taking advantage of the kinetic chain, check out Driveline’s guide for developing high-velocity pitchers: Hacking The Kinetic Chain. For more information on the author, visit www.treadathletics.com

Want to learn more about strength training as it relates to being a better pitcher? Read all of our articles relating to strength here.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

JoeM -

What about the deceleration of the hips in the kinetic chain at impact? Isn’t that an important part of the transfer of energy to the torso and shoulders?

JoeM -

To clarify my question. As weight is transfered to the front foot, the linear velocity of the hips decelerates. Then then there is peaking of the hip rotational velocity, but this happens before ball release, or ball impact with a bat. The hips are decelerating as the shoulder rotation is increasing. Looking at the above videos the hip rotation almost comes to a complete stop at release, then the momentum of the shoulder and arm deceleration after ball release causes the hips to be dragged around for further rotation. The rotation of the hips is not a one continuous motion, but two separate ones.

JimC -

Kyle, what are your thoughts on Lanz Wheeler and the Core Velocity Belt? According to what I can understand from what I’ve read about this Core Velocity Belt “Teaches Pitchers & Hitters What It FEELS Like To Build An Explosive Lower Half & Takes

Maikel -

I’m confused. Are you saying that as you drive, your drive leg is supposed to be rotated IN as you are going to the plate? That’s what it looks like with the still photos of Bauer, Chapman, Kofax. Check this link. https://a.espncdn.com//photo/2015/0208/mlb_u_dunn_300x200.jpg It’s a photo of Mike Dunn of the Marlins. His back leg doesn’t seem rotated in at all. I’m confused which one is best? He throws exceptionally hard as well, mid to high 9’s.

Relationship Between Vertical Jump Force and Pitching Velocity - Driveline Baseball -

[…] Instead of training for a sport specific skill that isn’t used everyday, such as a vertical jump, your weight training program should be focused on covering all three planes of motion. And if your scratching your head for ideas on how to do so, you’re in luck. We’ve talked about ways that you can train in the frontal and transverse plane before. […]