Facts Behind Running Poles in Baseball For Pitchers

With each passing day I become more convinced that we live in a world hinged on overreaction and overcorrection, the pendulum of opinion swinging from one absolute to the next without ever allowing for a balance of ideas. Should we be running poles in baseball practice?

Baseball and performance training are no exception to the rule. One generation adamantly ran poles after every outing. The next generation had disdain for anything that didn’t involve sprinting.

We should all observe critical analysis of methods seeking to improve sport performance. But, exclusionary thinking is very different than critical analysis. Only believing what you want to believe, or what you have personally experienced is called bias, not critical thinking.

Thus, when looking at conditioning for pitchers, we can’t run poles (or any form of aerobic training for that matter) just because generations past ran poles, nor can we avoid poles like the plague just because a couple of people said they will make you “less explosive.”

We touched on these topics earlier. But we must dig deeper.

Do we want to be running poles for baseball?

What is the Role of Conditioning and Running Poles for Baseball?

Conditioning centers on training the body’s energy systems and for the bioenergetics of sport. Ask the sprint-only advocate and you will surely hear that much of the action in baseball is predominantly in the ATP-CP pathway, or the anaerobic power system that is for actions lasting 30s or less.

Ask the poles-only advocate and you may not hear any substantial science at all. Perhaps you will hear some erroneous claims about lactic acid and soreness. Regardless of the rejected science you may hear about aerobic training from incredible sources on physiology, this does not make sprints the absolute.

In fact, much of baseball revolves around the aerobic pathway. Between jogging from point to point and the occasional plays that take the pitcher away from the mound in a hurry, the aerobic energy system certainly plays a role.

But, we certainly can’t stretch this to say that aerobic capacity is a major factor in the baseball game itself for a pitcher – on the surface at least. But, if we dig deeper we might find a handful of greater reasons to include aerobic training for pitchers, as well as a couple of alternative methods to execute this training outside of jogging from foul pole to foul.

It’s true, the role of conditioning goes beyond in-game sport performance. Another role of conditioning – one that isn’t always thought of immediately, yet is incredibly important – is in the recovery process. And, no, this is not about lactic acid. Any running program for pitchers should consider this highly.

Conditioning for Recovery

The recovery process within a game and in between appearances is highly dependent on the aerobic pathway. There are three different ways in which the aerobic energy system can make an impact on recovery:

- Recovering from any Glycolytic activity

- Increased Heart Rate Efficiency

- Parasympathetic Response

Although glycolytic activity doesn’t occur often in baseball, especially for pitchers, it can in fact happen.

More common, though, would be a practice session that requires the pitcher to go through his pitching or fielding work faster than he would during the game itself.

Regardless of the situation, an adequately developed aerobic energy system can only help to facilitate the transition back out of the glycolytic energy system (the energy pathway which causes that burning sensation in your legs as high-intensity efforts become prolonged). This is vital, as it will help avoid (or help clear) the accumulation of the metabolic wastes that cause the feeling of fatigue, and interfere with muscle contraction.

Also, aerobic training can help increase the efficiency of each heart beat. Thus, the heart does not have to work as hard to pump oxygen and nutrient-carrying blood throughout the body, even at rest. In this way the body is less taxed in general – during games and practice, and away from the field.

This brings up another vital point. It is important to understand that conditioning isn’t just for game-time performance. In fact, it can be just as impactful, or even more so when it comes to practice. The ability to practice at a high level, day in and day out, can dictate how much a pitcher improves, and ultimately how well they perform.

Finally, aerobic training can help manipulate the Nervous System for enhanced inter-game recovery, which is a focal point of this discussion. Let’s discuss more:

Using Conditioning to Manipulate the Nervous System for Recovery

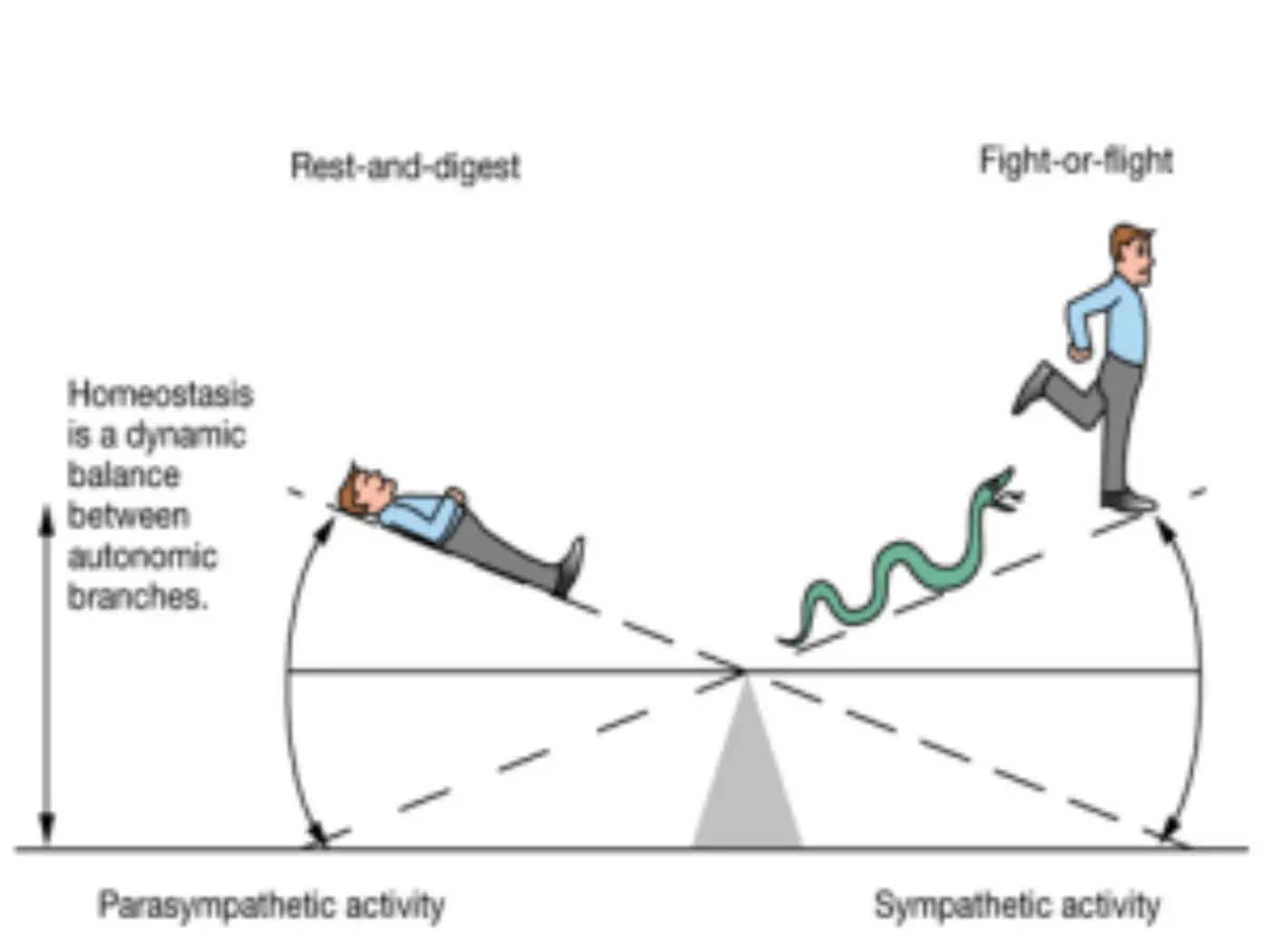

Recovery is also dependent on the nervous system’s ability to govern the body’s organs and their processes. The nervous system can be subdivided into Sympathetic (SNS) and Parasympathetic (PNS) divisions.

The SNS essentially elicits the “fight or flight” response. When the pressure is high (for example, when a pitcher first takes the mound in a big game) the body kicks into overdrive, prioritizing the systems that will best help it cope with stressful situations. It then inhibits those that are not needed.

For example, the hormone epinephrine is released to stimulate an adrenaline response. Meanwhile, the bladder is affected as well, as excreting waste is no longer a vital function for the current situation. How many times have you needed to urinate just minutes before the game, only to take the mound and forget all about it until the 3rd or 4th inning?

The PNS does the opposite by inhibiting the the SNS and its response. The PNS basically allows for optimal recovery, as everything from skeletal muscle tone to heart rate and sleep are all impacted in order to facilitate recovery.

Considering the pitcher gets major dosages of adrenaline two to three times per week in-season, not to mention strength training and practice sessions that generally trigger a sympathetic response, it is vital that the pitcher achieve optimal recovery in between appearances to allow for optimal tissue regeneration, adequate sleep, and ultimately peak performance in subsequent appearances.

Sprints, though, will not encourage a parasympathetic response – but aerobic training will. For this reason above all else I believe aerobic training should be included weekly on an in-season running program for pitchers.

Those that argue against aerobic training will cite the repetitive beating the joints already take when throwing a baseball hundreds of times each week as being more chronic stress that the body does not need.

I don’t disagree, which is why I advocate for other methods to facilitate recovery – methods that don’t include distance running or”running poles.”

Two Alternatives to Running Poles in Baseball Practice

Tempo Runs

One method that is incredibly easy to utilize in place of distance running or running poles for baseball as a means for aerobic training and recovery is the Tempo Run.

There are a handful of ways to do Tempo Runs, but I like to use them in the following manner:

- Establish a set distance in which to run. Normally, I use around 40-60 yards

- Take off from the starting point, gradually increasing speed until reaching approximately 70-80% of max speed

- This speed should be fast enough to create long strides, unlike that of a jog (i.e. short strides), but slow enough so it is not exhausting

- Once the distance is achieved, walk back to the starting position

- Continue for allotted time, usually 15-30 minutes

Using the Tempo Run will give the pitcher the same physiological feel as a distance run, without the monotony, repetitive pounding, and minimal effort strides. The elongated stride and arm action could also potentially aid in recovery via greater cyclical movement.

Recovery Circuit

How can we replace running poles for baseball without any running at all?

The second alternative method to replace distance running is a “Recovery Circuit” which can combine many recovery methods with an aerobic training component, making it a potent tool to recover after an outing.

The Recovery Circuit is composed of a handful of exercises that utilize movement to facilitate recovery, while also challenging the body just enough to mimic that of aerobic training, but not hard enough to challenge the body beyond that point.

Personally, I like to suggest stringing together a couple of mobility exercises for areas of need for pitchers (i.e. areas that normally lose range of motion over the course of a season, like scapular upward rotation), with an anti-rotation core exercise or two (in order to off-set all of the rotation experienced during the season), along with some SMR or passive stretches.

The SMR/passive stretches serve to not only facilitate enhanced tissue quality, but also to allow the heart rate to come back down, as not to raise up too high.

Also, if needed, a couple of “heart rate component” exercises can be used to bring the heart rate up if the circuit isn’t quite challenging enough. I almost always throw in a Kettlebell Swing and/or Squat to easily maintain that aerobic conditioning feel.

As for duration, I utilize the Recovery Circuit by continuously working for the allotted time – usually 15-30 minutes – without more than 10-20 seconds of rest at any one point. Again, this process should somewhat mirror a “distance run” in that we are sustaining a low-intensity effort with the aerobic energy system for a prolonged period of time.

Remember: the main goal of aerobic-based conditioning is to elicit a parasympathetic response from the Autonomic Nervous System, which can help enhance recovery. The Recovery Circuit is my favorite way to do this, as other modalities (such as active movement, mobility, and soft tissue work) can be included as well. There is a potential for a great return on investment with just 15-25 minutes of work.

***

When it comes to performance training, there are countless methods and protocols available for use. It is important to seek pertinent knowledge and to use critical analysis when interpreting this information, in order to find the optimal methods to enhance performance.

Conditioning has oftentimes been one of the most misunderstood aspects of performance training, especially in baseball. Thus, taking the time to evaluate the extent to which each energy system plays a role in practice and performance is crucial for the pitcher, as to not get caught up in the fallacies of misinformation. Running poles in baseball practice is likely not the best option.

My hope is that this discussion opens the pitcher and coach up to the idea that conditioning plays a much greater and varied role on performance and practice than what is seen on the surface. All it takes is a little bit of digging.

We’ve published other articles that are directed towards coaching, check them out here!

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Andrew Knutson -

Example of a recovery circuit you would use?

Ryan Faer -

Andrew,

Here’s one example:

20 Continuous Minutes of…

• Jump Rope x 50 (HR Component)

• Back to Wall Shoulder Flexion x 5 (Scap mobility)

• High Plank Shoulder Taps x 5 each (Trunk Stability)

• Kneeling T-Spine Rotation x 5 each (T-Spine Mobility)

• SMR Posterior Shoulder

• Goblet Squat x 10 (Heart Rate Component)

• Bretzel 2.0 x 3 each (Hip and T-Spine Mobility)

• Rotational Lunge x 5 each (Hip Mobility)

SMR Back

And here’s a blog post that I wrote on my own personal site discussing the Recovery Circuit in greater detail: https://ryanfaerblog.com/2016/07/07/pitchers-recovery-an-untraditional-approach-to-the-post-pitching-routine/

Keith Plemons -

What would you think about more aerobic conditioning for starters and less for relievers?

STUFF PITCHERS SHOULD READ | Tom Oldham Baseball -

[…] Facts Behind Pole Running For Pitchers – And Two Alternatives (by Kyle Boddy, Driveline Baseba… […]

Bullpen #3 and Post Activation Potentiation – The Minor League Offseason Camping Project -

[…] but I cannot stand distance running and it has been proven to be less than ideal for pitchers (SCIENCE HERE) so I probably won’t add it into my routine any time […]

Dave P -

As a track/wrestling/xc coach who has a boy in baseball, I appreciate much of the info you are providing others. I would have to agree with much of it, I think the number one component to keep in mind is that each athlete is their own and each individual has a method of training that best works their body. There are so many ways a body recovers and how your body responds to recovery. I chose to use many proven scientific research on athletes to dictate much of how I coach my athletes, but I know that every body responds differently. I’m not a pitching coach, and probably understand more about recovery than many coaches, because of those scientific principles. Just because you don’t like long runs doesn’t mean it isn’t useful. You have to more importantly know and understand the periodization of your training and implement a variety of spint and recovery training to address issues from muscle imbalances, biomechanics, as well as aerobic, anarobic, and anabolic muscle responses. Additionally, muscle maintenance cannot be ignored. Teaching the pitcher to be an athlete, not just a baseball player or pitcher should have a much greater focus in school aged kids. Teaching them to not specialize is equally important and can address many of these issues. I like this article because it can get the average person to begin an understanding of training is more than running or some workout to make you stronger, but to recover the body in a smarter efficient way. There are so many ways to recover the body you just have to care enough to learn cutting edge techniques and prepare for your season months before instead of in your way to practice as many coaches do. Thank you for reposting this article.