Measuring Recovery of Baseball Pitchers Using Omegawave and HRV

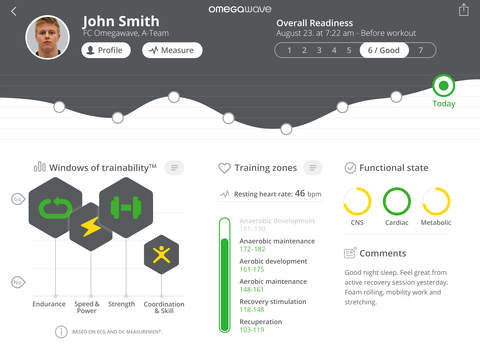

In an effort to improve our own programming, we tested our athletes using the Omegawave this summer. Omegawave is a device that, after a few minutes of measurement, gives you a number of metrics that help decide your readiness to work out.

At it’s core Omegawave focuses around measuring direct current potential of the brain and heart rate variability to create a daily profile on an athlete’s recovery status and workout readiness.

Beyond Training Periodization

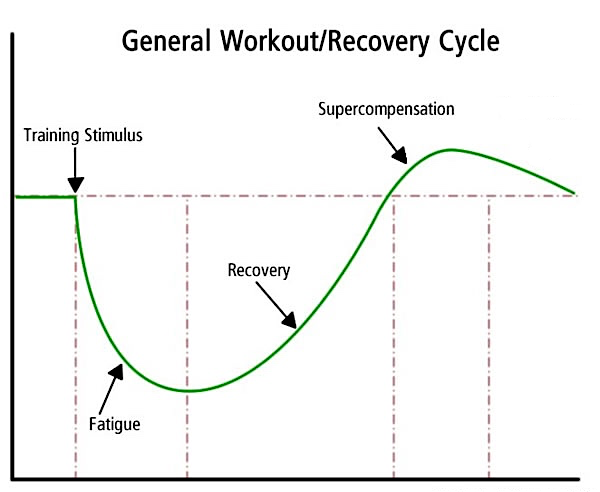

Ideally the Omegawave would help us expand on Selye’s general adaptation cycle and past block periodization scheduling, thus enabling us to create more individualized programs per athlete based how their body is reacting to training.

If they measured low/unready on a day they were scheduled to perform high intensity tasks like weighted baseball pulldowns or Plyo Ball ® velocity tests, then theoretically we could bump that to the next day in hopes of being better rested or just reduce the workload. Changing throwing schedules does already happen at Driveline through athlete and trainer communication, but the Omegawave could potentially give us a more steady, reliable, and regular measurement.

As mentioned in a previous blog post, Selye’s general adaptation cycle

We are aiming to get a reading on an athlete’s readiness beyond what we can measure in the gym. We can measure the number of throws, how hard they throw, and how much they’re throwing on one day or week, but this doesn’t cover everything that can affect performance.

There are a number of stressors that will affect their performance beside in gym workload: inadequate sleep, lack of proper nutrition, financial stress, social stress and other mental stress, all of which has research backing those stressors’ negative impact on training.

“This investigation demonstrates that chronic mental stress has a measurable impact on the rate of functional muscle recovery from strenuous resistance training over a 4-day period. Specifically, higher levels of stress resulted in lower recovery curves and, conversely, lower levels of stress were associated with superior levels of recovery.”

We used the Omegawave to test this idea because it it suppose to go a step beyond measuring just an athlete’s heart rate variability. Research has suggested that Heart Rate Variability (HRV) should give a glimpse into how an athlete is responding to training, but its actual implications for baseball training are as of yet unknown. Heart Rate variability gives us a picture of the status of an athlete’s autonomic nervous system (ANS) by measuring the time in between heartbeats. ANS contains both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system which help regulate the homeostatic functions of the body, which is useful because it is a simple and non-invasive form of measurement.

The following study proposed a hypothesis that Heart Rate Variability is a useful measure to include when trying to measure the workload and possible overtraining that an athlete may be experiencing.

Musculoskeletal overuse injuries and heart rate variability: Is there a link?

“Research findings indicated that HRV may provide a reflection of ANS homeostasis, or the body’s stress-recovery status. This noninvasive marker of the body’s primary driver of recovery has the potential to incorporate important and as yet unmonitored physiological mechanisms involved in overuse injury development.”

Given the evidence found in peer-reviewed research, we decided to run a trial with a handful of athletes at the beginning of the summer just measuring their high output days (weighted baseball pulldown and Plyo Ball ® velocity tests) to see if we could find a link between their scores on that day and their performance, looking to see if there was a correlation between the metrics and how many personal records they broke.

The link between readiness score and personal records wasn’t as clear as we hoped. We can also compare the number of PRs broken depending on the athlete’s overall readiness score and it seems almost even for both the high and middle readings. Though note the 6-7 range was strongly carried by one athlete; remove his readings and the 3-5 range becomes the winner.

The numbers ended up showing that the athlete had the possibility of breaking PRs as long as they didn’t measure on the lowest end of the scale. We didn’t see a relationship that showed the higher they measured the more likely they were to break a PR, though it was with a relatively small sample.

We can also look at the results and say athletes are good to train as long as they aren’t on the lowest end of the scale. The Omegawave does give us a great representation of how the body but that may not be entirely representative of how an athlete’s arm is feeling. Specific arm soreness may be a factor that doesn’t have a relationship with total body readiness, which could be a part of a possible explanation for why athletes had such a large range of readings in which they broke PRs.

This also goes back to our theme of how velocity development isn’t linear. It doesn’t mean that every time you feel good, you’re going to break records. You can take care of yourself for weeks and not break PRs every time, but that doesn’t mean that you aren’t getting a good training stimulus in – short-term results do not dictate training improvements.

Where we could do better

One important note is the Omegawave teams suggests testing yourself at the same time every day under the same circumstances for the best results – preferably in the morning 30+ minutes after waking but before food and coffee. Unfortunately, because of our athletes’ throwing schedules, we weren’t able to do that. When we move to measuring athletes everyday they often ended up coming in at different times of the day which affects where they are in their circadian rhythm, how much and what they’ve been eating, and caffeine or other stimulant intake.

It’s difficult to compare two athletes physiological readiness levels when one is throwing at 11 AM after a light breakfast and coffee while the other is throwing at 4 PM after breakfast, coffee, lunch, and a Red Bull or Spike.

The specific time that training occurs is important because our bodies have adapted to a 24 hour circadian rhythmic cycle, which helps regulate when we sleep among other physiological processes – meaning that your hormones are not always at the same levels but cycle up and down throughout the day.

Experiment part 2

Nearing the end of this experiment, we realized that we should look at the bigger picture of athletes training by measuring them everyday, and that coincided with the release of this study.

Resting Heart Rate Variability Among Professional Baseball Starting Pitchers.

Following 8 Single-A professional pitchers they measured each pitcher’s HRV every day for the whole season. They found that they day after a start resting HRV was significantly lower than all other rotation days.

Keeping the study design in mind, we chose a couple of pitchers to look at over a longer period of time – at least 5 days of training – to see how the results would look in comparison to the findings of the study. Would we see a difference?

A few pitchers did seem to see the expected reaction of a drop in readiness after a high output day – but not all.

We did see that each athlete had quite a different response to the training stimulus. So the data confirmed a previous hypothesis that different athletes are going to have different responses to the same or similar training programs.

What we learned

What we did take from this experiment is that we could better integrate athletes throwing and lifting programs. Athletes come in with different lifting and throwing abilities and train here for different lengths of time. We do the best we can in scheduling, but there’s always room for improvement. Using the Omegawave gave us a glimpse on how we could better integrate what athletes did on their lifting days with their throwing schedule.

Secondly, it reaffirmed the idea that athletes need some time to learn appropriate exertion levels for recovery, hybrid, and high output days. Even if athletes measured low on a high output day, that doesn’t mean that if they feel good on a recovery/hybrid day that they should try to blow up the radar gun – which is something that takes some time for the athletes to learn!

The majority of this article was written by Michael O’Connell, who is our first analyst in the Research and Development department of Driveline Baseball. He and Joseph Marsh (an intern in the R&D team) collected the data and designed the study. This article was edited and approved by Kyle Boddy, President/Founder of Driveline Baseball.

Want to learn more about strength training as it relates to being a better pitcher? Read all of our articles relating to strength here.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

STUFF PITCHERS SHOULD READ | Tom Oldham Baseball -

[…] Measuring Recovery of Baseball Pitchers Using Omegawave and HRV (by Michael O’Connell, Driveli… […]

Weighted Baseball Training - A Getting Started Guide -

[…] Driveline Baseball, we constantly test training and recovery implements for our pitchers. Most won’t surprise you – we use free weight training with barbells […]