Everything Push-Up: why you need it, how to teach it, ways to progress it – Part I

There are many different ways to select and utilize exercises in order to compose a successful strength-training program. Regardless of which variations you select, the staple movements of most complete programs include the following:

- Squat

- Hinge

- Lunge

- Pull

- Push/Reach

- Carry

- Rotation

In this series we will discuss an exercise that falls within the Push/Reach category – an exercise that reigns supreme in the world of baseball performance training: the Push-Up.

Today, in Part I of this two-part series we will touch on the significance of the Push-Up, as well as a means to teach it. In Part II we will go over a series of progressions and variations to ensure that you get the most out of the Push-Up during the year-round training plan.

WHY THE PUSH-UP?

It’s hard to quantify all of the reasons the push-up is such an essential exercise for the baseball player (and all athletes in general). Let’s look at a handful of them (in no particular order):

1.Improving true relative strength

Relative strength is defined as a ratio of strength to bodyweight. Although this can be used to measure an athlete’s strength in nearly any upper-body exercise relative to bodyweight (e.g. a 200 lbs athlete Bench Pressing 315 lbs) what strength is more relative than an athlete’s ability to move their own bodyweight through pulling and pushing? Thus, the Push-Up, Pull-Up, and Inverted Row are three great exercises for determining relative upper-body strength.

2. Postural Awareness

The “High Plank” (a traditional plank, except with elbows fully extended; in other words, holding the top of the Push-Up) is a tremendously simple yet effective exercise for teaching posture. From lumbopelvic control, to scapulothoracic positioning, the High Plank alone does a great job of putting an athlete in a position to learn and control for posture. The Push-Up, then, challenges that acquired awareness and control of posture by adding dynamic movement, and it does so in a way that the Bench Press and its variations simply can not.

3. Trunk Stability

Additionally, the High Plank is an effective exercise for building trunk stability and core strength. Being able to properly align the segments of the body, and subsequently control for this under movement and stress is the essence of trunk stability training. Just lowering one’s bodyweight into the bottom position of the Push-Up poses a challenge to postural integrity. Ascending back to the top can be even more difficult.

4. Scapular Positioning

When done correctly, the Push-Up performed through a full range of motion (more below) not only trains upper-body strength, it also develops strong positioning of the scapula on the thoracic spine and rib cage. For the baseball player, scapulothoracic positioning is vitally important in terms of shoulder health and performance, thus dysfunction in this area should always be addressed. Many of the possible dysfunctions in this region can be remedied by a proper Push-Up and its variations.

5. Freedom of the Scapula

Ultimately, the most significant difference between the Push-Up and other pressing exercises, such as the bench press, is the freedom of the scapula to move, and for actual glenohumeral rhythm to occur. The Closed Kinetic Chain (CKC) nature of the Push-Up allows the scapula to move freely throughout the movement (retraction as the athlete descends, protraction as they ascend). Whereas, with the Bench Press, the scapulae must stay locked down in retraction on the bench for the duration of the movement in order to ensure shoulder safety, and to minimize the amount of total work necessary to complete the lift.

Throwing a baseball requires the glenohumeral joint (in conjunction with all surrounding joints in the Kinetic Chain) move optimally and freely. The Push-Up not only matches this movement demand, but it also encourages the development of safe and strong shoulder function.

HOW TO TEACH IT

When teaching the Push-Up, the coach should avoid taking out the trunk stability components simply to make it easier. For example, we should not put our athletes on their knees to make the exercise easier on the upper-body. It is vital to progress and regress the entire movement as a whole system, rather than focusing only on upper-body strength. This is because enhancing upper-body strength alone will not concurrently develop trunk stability, postural awareness, etc.

Thus, we should select teaching regressions and progressions that not only adequately challenge the strength of the athlete, but also appropriately develop postural awareness, and bring along trunk stability as well. Additionally, appropriate regressions/progressions place the athlete in the best environment to learn new movements.

There are a couple of “check-points” that must be observed in each phase of the progression before moving on to the next variation. Personally, I like to see the following:

- Neutral lumbar spine

- Actively contracted Glute Max

- Hands in the same plane as the shoulders

- Hands slightly wider than shoulder-width

- Protraction of the Scapulae

- Elbows at 45* angle relative to the trunk

- Neutral neck

The athlete first must be able to attain this positioning in a static position before movement can be added, and then the athlete should maintain all of these “checkpoints” despite movement and fatigue. The Push-Up will not be progressed until these checkpoints are met and maintained under increasing stress and fatigue.

Above all else, these two themes are most emphasized early in the program:

- Scapular positioning

- Lumbopelvic positioning and control

In order to do this, we always start with the High Plank as our base regression for the Push-Up (as well as for Trunk Stability programs).

The most effective cues I have found have been the following:

“No soft shoulders. Push the floor away” for scapular protraction, and

“Belly button to spine” for lumbar positioning

Also, I will place them in a position to meet these two cues by starting them in a Quadruped position, and then taking them into the High Plank.

Upon showing proficiency in maintaining the proper High Plank for roughly 30 seconds, we then progress to Eccentric-Only Push-Ups on the floor, and Concentric Push-Ups from a regressed, hands-elevated position.

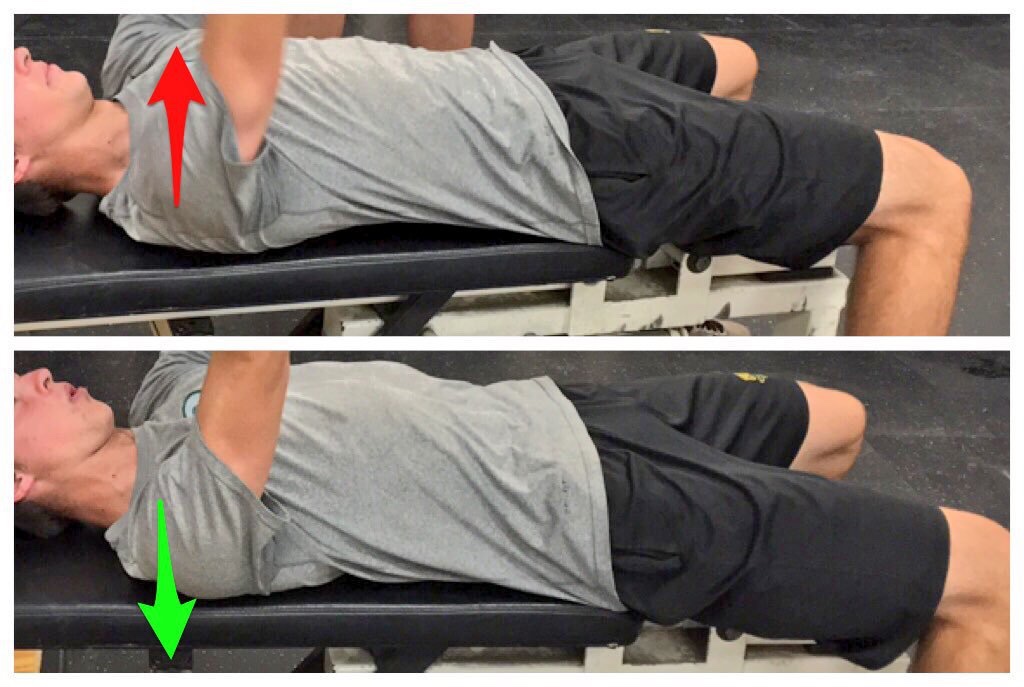

Eccentric-Only Push-Up

Once the athlete has shown proficiency in the static High Plank position, we begin to challenge it by adding dynamic movement. Most novice trainees experience the greatest difficulty maintaining posture during the ascension from the bottom back to the top of the Push-Up, thus we use the Eccentric-Only Push-Up to develop upper-body strength and incrementally challenge posture and stability without overloading it to a breaking point.

Additionally, because the athlete does not perform the concentric phase during the Eccentric-Only Push-Up, they must reset to their High Plank every single rep. Thus, 3×5 of the Eccentric-Only Push-Up forces the athlete to properly position and align themselves fifteen times, without having to explicitly dedicate time to working on the High Plank.

Generally, we will emphasize a 3s eccentric and a 3s isometric on each rep.

Concentric Push-Up from Hands-Elevated Position

Initially the Eccentric Push-Up is used individually and alone. But, as this becomes easier (which happens quickly as the athlete sees progress rapidly in the initial stages of training) we begin to pair it with full push-ups (Eccentric and Concentric) where the hands are elevated to the appropriate height. By elevating the hands, the upper-body strength required to complete the lift is lessened. But, unlike the push-up from knees, the hands-elevated position still challenges posture and stability, thus maintaining the bang-for-the-buck of the true Push-Up despite being regressed.

In general, this pairing of exercises may look something like:

1a. Eccentric-Only Push-Up from floor (3s eccentric + 3s isometric at bottom) – 3 x 5

1b. Concentric Push-Up from hands-elevated position (1s eccentric + 1s isometric + 1s concentric) – 3 x 8

Once the athlete shows an ability to proficiently stabilize the trunk and control posture thought the movement, while also exhibiting the strength to complete the desired repetitions, we can begin to progressively remove the Eccentric Push-Up volume, while simultaneously lowering the height at which our hands are elevated.

After a few weeks/months, most athletes (with reasonable body weight/composition and strength) tend to progress to the floor and use traditional Push-Ups.

In Part II of this series we will discuss ways in which to add variety and progression to the traditional Push-Up to ensure that it can be effectively used year-round with athletes of varying training capabilities.

Looking for a way to program push-ups into your pitching work? We use high planks and push-ups as foundational strength movements in our youth pitching program, Hacking the Kinetic Chain – Youth.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Everything Push-Up: why you need it, how to teach it, ways to progress it – Part II - Driveline Baseball -

[…] Part I of this series covered the basis of why the Push-Up is such a beneficial exercise for the developing baseball player – and really, any athlete in general. The benefits discussed ranged from teaching postural awareness to enhancing lumbopelvic control and trunk stability, from improving relative upper-body strength to incorporating proper scapulothoracic and glenohumeral movement. The Push-Up truly is an over-achiever in the “bang-for-your-buck” department. […]