Building Your Team’s In-Season Training Plan – Part III

In the first piece of this three-part series we discussed the overall importance of in-season training for the high school baseball player, and how it fits, philosophically, within the context of the spring baseball season.

Part two covered the considerations that should be taken when planning out the in-season training program – laying out the game and practice schedule, having multiple training modes prepared, and maintaining flexibility in your programming.

In this discussion, our final installment, we will look at how to structure in-season training sessions in order to get the most bang for your buck, while also minimizing the amount of time spent in the weight room.

Identify the Non-Negotiable’s

Time spent in the weight room should be centered on two things:

1. The aspects of training that are most important to sport performance and that cannot go an entire season without being addressed

2. Aspects and modes of training that cannot be addressed on the field

With these two stipulations in mind, we can “trim the fat” of each training session in order to focus on the bulk of the meat.

Some non-negotiable’s of in-season training include total-body strength, power, and mobility. An entire in-season period of several months without these qualities being addressed would lead to decrements in strength that would ultimately see a reduction in power. It would also allow the insidious progression of musculoskeletal adaptations in response to throwing, such as augmented ranges of motion at the shoulder and hip.

Neither one of the above scenarios is ideal for a baseball player of anyone level. And, given the relatively less demanding schedule of high school baseball compared to higher levels of the sport, there is no reason strength, power, and mobility shouldn’t be addressed.

Trunk stability and “arm care” too are vital, especially in order to off-set all of the game and practice loads that the players experience in terms of rotational movement (i.e. throwing, swinging).

With these five “non-negotiable’s” in mind, let’s discuss some ways to maximize the exposure of our athletes to these qualities of training, while minimizing the amount of time and energy taken away from games and practices.

Address What You Can at Practice

Of the above non-negotiable’s, quite a few of them can be trained outside of the weight room. While strength, and oftentimes power need heavy loads of select equipment to best drive their adaptations, performance qualities such as tissue quality, joint mobility, and trunk stability need little by the way of equipment, space, or even time. Thus, there is a great potential to address these aspects of training on the field before, during, or after practice. And, because of this, not only does that eliminate the need for additional time-costly training sessions in the weight room, it also means that they can be addressed often, if not every single day.

For tissue quality and joint mobility, the greater the exposure, the more likely we are to see substantial changes, rather than transient ones. Thus, working soft-tissue modalities (such as foam rolling with a roller or baseball), or addressing mobility can be used daily in smaller, yet highly effective doses.

One of the easiest ways to work in mobility and tissue quality is to include them in the warm-up, as the warm-up is conveniently used every day. Rather than glazing over during a monotonous warm-up, treat it as a prep session that addresses the needs of the individual, or the overall needs of the team.

As for stability and “arm care”, these can be included in the warm-up as well, or around the various practice session stations. In fact, they can be a station all to themselves; they need not but 5 minutes or less if their is a focused plan and attitude. Regardless of how you integrate these aspects, their frequent inclusion will help the athlete become more cognizant of posture, while also helping to cement stability through strength.

This is not to say that any of these qualities can’t or shouldn’t be addressed in the training session as well, but the most prudent suggestion would be doing so only in order to emphasize what you feel needs additional focus, not just for the sake of including more work (and using more time).

Select a Focus for Your Training Sessions

When developing the training sessions themselves, you should always keep in focus the goal of the session. Remember, we are training for performance – we are not exercising.

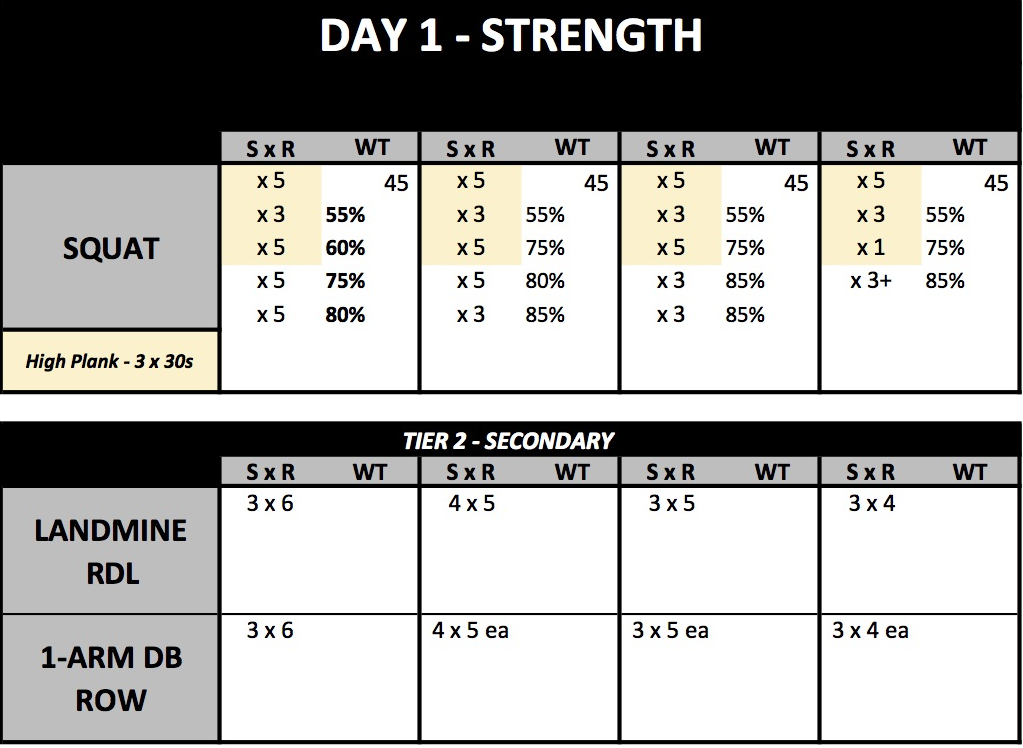

For example, if we are looking to maintain or gain strength, we should not be programming sets of 12 reps on the Squat. Rather, high intensity sets of 2-6 reps could be used to stimulate the muscles to produce great amounts of force to overcome the load. Likewise, with the goal of maintaining or gaining strength in mind, we should not rush our players to perform sets in 60-90 second intervals just for the sake of time or “hard work.” In order to produce maximal force from set to set, we must allow for adequate recovery times in between sets.

Power, too, should be similarly focused. Power production capabilities will taper off as muscular and neurological fatigue accumulates. Thus, high rep sets of box jumps, cleans, med ball work, etc. will eventually lead to sloppy, unfocused, and non-maximal effort work. Again, rest is vital as well.

Hopefully you are starting to realize a major theme to in-season training: volume is not the priority. Thus, we should focus our time and energy on what is most appropriate: strength, power, and any recovery that is necessary.

One way to ensure that the focus is always simple to understand and implement is to divide the training sessions, each with one narrow focus.

While we could spend a little time of power, and a little time of strength, and a little time of pre-hab, etc. each session and get away with it (young trainees get good results with “mixed training” as this would be called), it could be hard to explain at times, and tough to ensure that the focus remains intact during the in-season. It can also make flexible/adaptable training schedules harder.

Instead, you could spend one thirty-minute session on strength each week, one thirty-minute session on power/speed, and one session on recovery/mobility if a third day is allowed given the time constraints.

Moreover, a week can see any given combination of these sessions. If the team seems to be fatigued, a recovery/mobility session may be a better choice that day than say, a power session. Regardless of which sessions are selected each week, the focus of each session will remain constant to that day’s theme: if it is a power day, the athletes know they must move the weight fast, and if it is a strength day, they know they must exert some serious force.

Structuring The Training Session

It should be noted that there are many effective ways to structure a training session. Regardless of how you choose to do so, you should be mindful to keep the training goals in focus at all times, and also strive to minimize the time necessary to accomplish those training goals.

It may seem obvious to many, but the easiest way to maximize time efficiency is to actually eliminate training sessions. This means refraining from training splits that require more training sessions than necessary. By moving away from two upper-body and two lower-body sessions per week in order to use two to three total-body training sessions, we can eliminate hours of work and get the same goals accomplished.

Additionally, time can be best used within the session itself by utilizing active rest, whereby a rest period for the lower-body is occupied by an upper-body exercise or some other non-lower-body taxing exercise.

In our lifts, we may select an emphasis for the day, such as the Squat. This exercise will only have a trunk stability or a mobility exercise paired with it. In that way we are using our rest periods judiciously, yet not overtaxing the body – even an upper-body exercise during a rest period can make the Squat feel that much harder. Additionally, we may have mismatched sets for that emphasis. In other words, we may have 5 sets of Squats, but only 3 sets of a trunk stability exercise. The purpose of these mismatched sets is to ensure that the most physically demanding sets have zero interference from any other exercises during rest.

Beyond our “emphasis”, we might pair upper-body and lower-body exercises the rest of the way. For example:

Again, the overall idea is to maintain focus on very specific training goals during our sessions, while also minimizing the time needed during training to foster these adaptations.

***

When it comes to in-season performance training, a handful of very important themes must be held onto closely:

- The main goal of the season is to perform at a high level and ultimately to win games. We cannot lose sight of this.

- At the high school level, though, development must also be a priority. Proper in-season training can develop a young athlete, yet still allow them to compete at a high level and be put in the best position to win.

- The high school student-athlete is still maturing, not just physically, but mentally as well. Thus, we cannot just inundate them with practice, games, training, etc. on top of school, and everything else in there life. Rather, we must help them balance only what they are capable of handling. Training must be flexible and adaptable.

If the coach keeps these key concepts in mind, in-season training is sure to become a successful component of the competitive season at the high school level.

Comment section