Hacking a Pitcher’s Arm Action: A hidden power of overload training

This article lays out the case disputing “weighted baseball training being more injurious to pitchers than regular baseball throwing”, and talks through one of the mechanisms that lessens a pitcher’s injury risk when training correctly with weighted balls, and increasingly more efficient set of pitching mechanics.

Weighted baseballs can be controversial. I get it. If throwing a regulation 5oz ball leads to insane injury rates amongst pitchers, even at the highest levels of the game, the thinking goes, then, that heavier balls must equal more stress, stress is BAD, and injury rates would be higher. Furthermore, there is a fear that weighted implements might actually screw up a pitcher’s arm action, since they have become accustomed to throwing a regulation ball their whole life. Unfortunately, these interpretations fail to understand both the basic mechanism of adaptation to stressors and the actual biomechanical outcome of throwing weighted implements.

The misinterpretation of stress as being bad: a failure to understand how velocity is increased

To increase pitching velocity, we need progressively increased but intelligently managed stress over time to drive our bodies to continue adapting and strengthening. This is called the SAID principle in exercise physiology, which stands for Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands.

Your body will adapt to the specific stressors / stimuli being applied to it – if a stressor stays exactly the same, week after week, month after month, adaptation comes to a halt. This intuitively makes sense – you wouldn’t lift the same weight every week and expect to keep getting stronger without needing to add weight or reps.

We Already Applied Stress Adaptation Training in Baseball

We also acknowledge this fact when it comes to throwing regulation baseballs – progressively trying to long toss further (increase intensity) or gradually do more daily throws in bullpens, games, etc (increase volume). Most coaches accept the fact that we need more stress to build arm strength. Arms take time to “get into shape” and we are okay with overloading the tissues progressively via increased intent and/or volume.

Increasing the load, however, is just another way of varying the stress on the body to achieve the desired outcome, which, presumably, includes increasing throwing velocity. Nobody is saying to go long toss with 10lb balls, just as nobody would advise throwing 200 pitch bullpens every day of the week.

There are safe and progressive methods for incorporating overload principles into an athlete’s throwing without compromising recovery ability.

Yes, but wouldn’t weighted balls “screw up” a pitcher’s mechanics and mess with their command?

Efficient arm action and refined command are not 100% linked. From a purely biomechanical perspective, I define an efficient arm action as one that allows for maximum application and transfer of kinetic energy into the ball. A efficient arm action, first and foremost, is one that helps you throw hard. Weighted implements are therefore tools to create better efficiency.

However, command is complex. It is a product of a high number of repetitions and deliberate practice with a refined motor pattern. There is also a large mental component. Of course, more efficient and well-coordinated mechanical movement patterns should help improve command once the athlete has had enough repetition to internalize that pattern.

For a lower velocity pitcher who has adjusted to and even mastered sub-optimal mechanical patterns after tens of thousands of repetitions, re-mapping his arm action will likely cause an initial decrease in ability to locate pitches, but it is a one step back, two steps forward scenario. Suddenly his ceiling is 88mph instead of 82 mph, for example, and he now begins learning to harness a newer, more biomechanically efficient movement pattern.

Is taking a small step “back” to re-map an athlete’s arm action worth it?

That’s up to the athlete or coach to decide. There will be a learning curve and adjustment period to any mechanical change. Barry Zito, in his prime, was dealing at the major league level throwing mid to upper 80s – only a fool would have told him at that time that he needed to re-work his arm action to get to a 95 mph ceiling.

But let’s consider a high school pitcher throwing 81 mph or a collegiate pitcher throwing 87 mph – is the goal to just have a successful senior year and then hang up the cleats? Or is the goal to get your foot in the door at the next level? Why spend effort refining an inefficient movement pattern if you are trying to further your career at the next level? I constantly fought advice at every level of my career to “just throw strikes” because I kept the bigger picture in mind. I could have refined my 84-87 mph sophomore delivery, probably played more and put up better college stats that year, but I chose the path that would give me a shot at reaching the next level.

Unless you are already at the professional level, velocity is what matters for continuing your career. Even at the pro level, the finesse pitchers are given less opportunities and generally face a much harder uphill battle to progress through minor league systems. Not because they aren’t good enough, but because who is going to give an 84 mph crafty lefty a shot when there are dozens of 95 mph arms around him – he has to flat out dominate to claw his way to each successive level of the minor leagues while the 97 mph pitchers get promoted with ERAs of 7.00.

The point being that making any kind of change to a pitcher’s mechanics might mess with their command, initially. However, rather than “screw up” a pitcher’s arm action, weighted balls continually appear to show this “re-mapping” effect where they create more biomechanically efficient movement patterns (increased efficiency of force transfer).

Need a Program to Help Get you to the Next Level?

We have a training option that is right for you.

What does this arm action “re-mapping” look like?

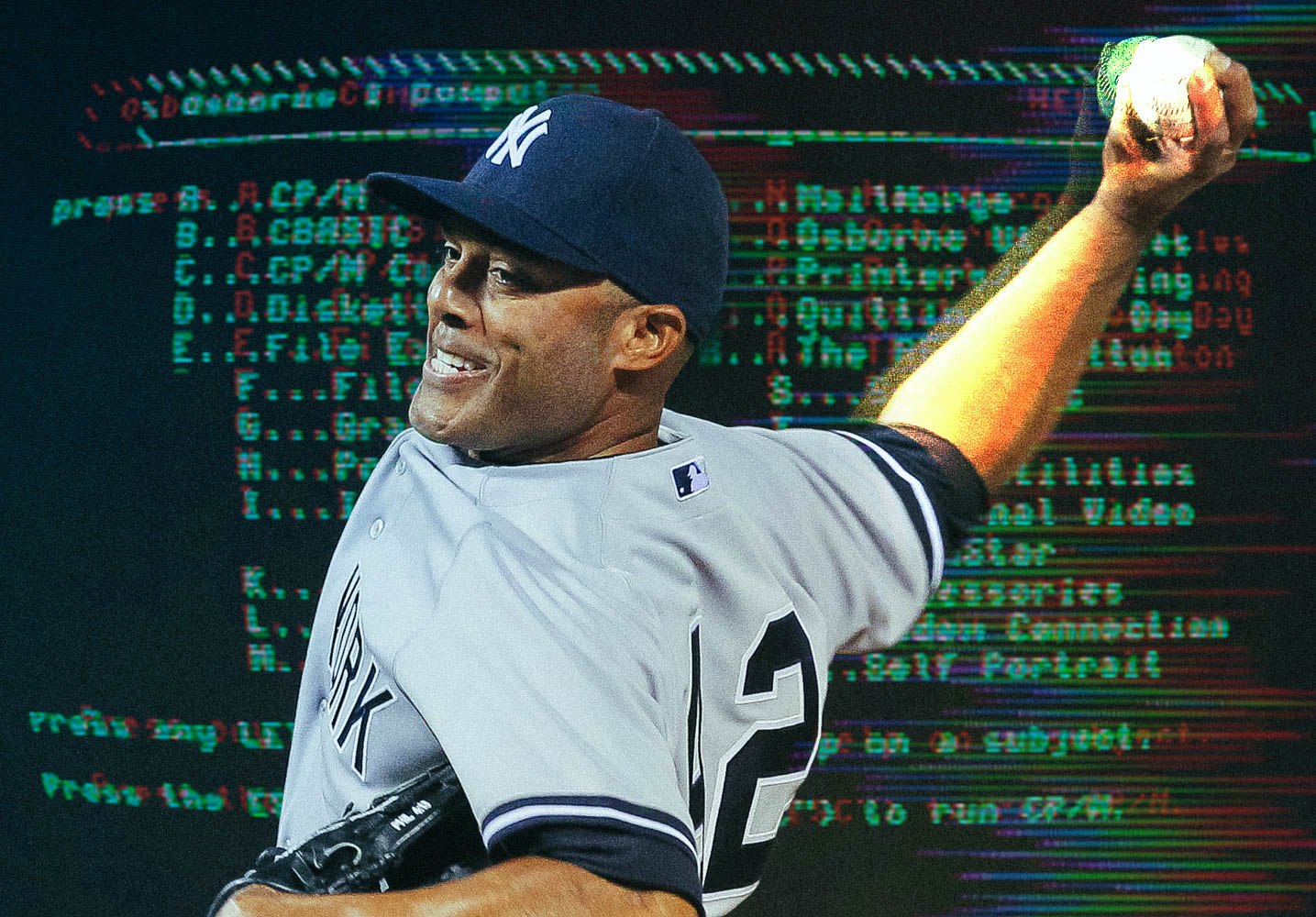

Here is Brady, a college sophomore. He had been stuck at 82 mph for 2 years when he visited us. Intent was not his problem (he throws the crap out of the ball), neither was strength (all his numbers are in the 95th+ percentile for his age), or mobility (ankle, hip, thoracic, gleno-humeral, scapulo-thoracic all good). What he had was an inefficient arm action.

With some instruction on what exactly his mechanical deficiencies were, and an idea of what he was trying to achieve and feel with the weighted ball drills, he threw 86 mph several days later even after just learning the new movement and after the high volume of resistance training and throwing he had been doing that week.

Experience tells us that once he fully internalizes and masters the new movement pattern (synchronizes his hips, torso, etc. as he continues strengthening those new neural pathways), more velocity is up for grabs.

Of course this was not the only way for him to have learned a cleaner arm action. But the weighted balls allowed him to “feel” it and speed up the coaching/instruction process tenfold.

What does throwing weighted balls feel like?

It might be hard to picture what weighted ball training is like if you have never done it. First, consider that the weight of a baseball is somewhat arbitrary. Footballs are 14-15 oz, tennis rackets weigh anywhere from 8 to 12 oz and softballs are roughly 6.5 oz. There is nothing inherently special about 5 ounces besides the fact that it is the weight you used since you were in little league (when, by the way, that 5 ounces was far heavier relative to your body mass, hand size, arm length, tissue strength, etc.). For an 8 year old weighing 70lbs, that 5oz baseball was big and HEAVY. For a strong 25 year old at 6’5” 230 lbs, that thing is like a golf ball. It’s totally arbitrary.

Throwing a significantly heavier ball (1-2lb+) should feel “connected,” “fluid,’ and “whippy.” It’s like the ball is telling your arm where to go. This is not a scientific description, but it’s unanimously what the collegiate and professional players training at Driveline Baseball describe as the feeling.

Overload Training and Improving the Kinetic Chain

With a heavier ball, there’s more resistance for your arm and body to use as a guide through space and time. You must conserve the momentum of the ball on the arm’s downswing, and efficiently transition and transfer force throughout the arm path to execute the throw with any sort of intent or fluidity.

If you have an egregious timing issue or hitch in your arm path, the heavier the weighted ball, the harder it will be to get away with flaws. The more efficient your arm will have to become in order to propel the object with any meaningful amount of force.

For example, try throwing a football with a long arm swing behind your body or with an inverted-L position at landing – it just won’t happen. Your arm is guided by the constraints of the task (the shape, weight of the object, the target, etc.). In this case, the heavier weight is a very loud and constant feedback loop that makes it incredibly difficult and awkward to have massive arm action inefficiencies.

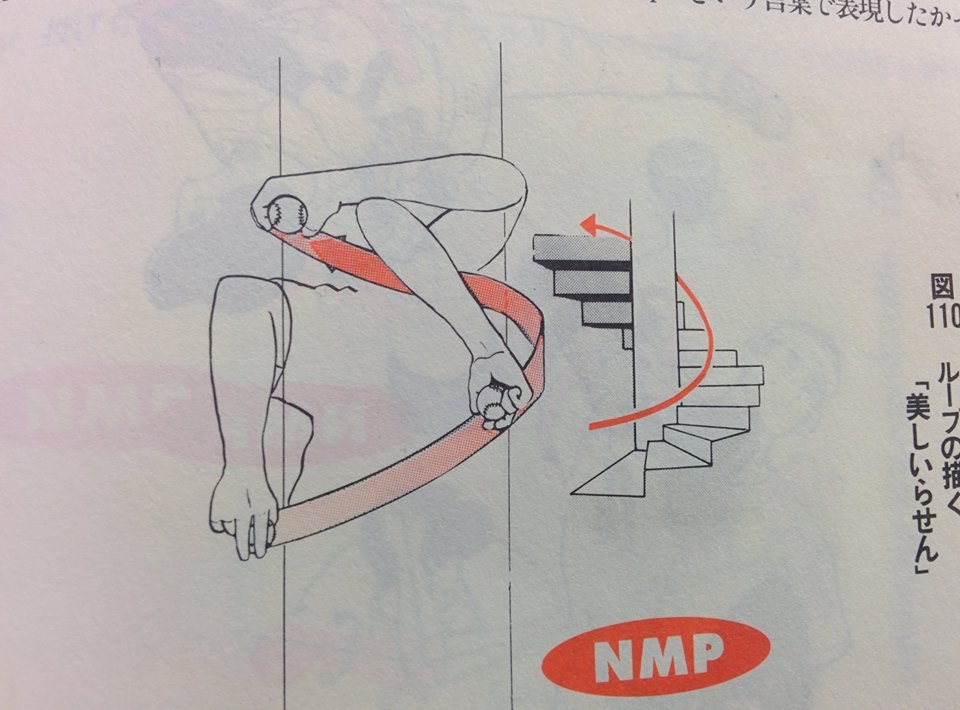

This is not to say that just picking up a heavier ball will give you a perfect arm action. Slight arm action inefficiencies may still be present, in which case the weighted balls will still speed up the coaching process by allowing the athlete to instantly feel to a much greater extent whatever arm action tweaks the coach is attempting to make. Pushing a 2 lb ball feels labored and awkward, but feeling a connected arm spiral “up the staircase” is a breeze.

More tips on throwing weighted balls, and throwing hard in general.

- Let the throw loosely unfold, pulling down aggressively as the ball begins to accelerate.

- Don’t “muscle” the throw from the first movement of the hands separating, this has a tendency to screw up proper sequencing and ruin the smooth flow of energy.

- Think about how you crack a whip or a wet towel. There is looseness to the wrist, fingers and elbow until the final CRACK. It’s the same “wave” of energy that you should feel in your arm action. Sure, there is a small amount of muscular activity being used to initiate your arm action, just as there would be to initiate the countermovement of a whip strike, but it’s a loose, fluid and connected “wave” of energy until the final CRACK (the “pulldown” phase) once your front leg has braced, hips have opened and now all this potential energy and proper sequencing can be unleashed via active intense muscular contraction. You see the same phenomenon with boxers or martial artists, who rely exclusively on the kinetic chain to sequence complex movements and generate power – throwing a powerful punch is loose and connected, driven from the hips up the torso until the final POP just prior to impact.

- This video shows the whip-crack mechanism in slow motion. Pay attention at the 0:25 mark. The “spiraling of the staircase” is this loop or “wave” that we are creating in our arm action. This is the effect we are after in the throwing motion as well.

Weighted Baseballs are a Training Tool: Some Perspective

Weighted balls are just another training tool to use, just like long toss. There are hall-of-fame pitchers that loved long toss, just as there are hall of fame pitchers that never threw a ball over 60 feet in catch play. It’s about what training tools and techniques produce the desired level of performance.

For those of us who can’t just roll out of bed and chuck a ball 90 miles-per-hour, it’s always worth keeping an open but critical mind of whatever possible tools may best help you achieve your end goal. Don’t blindly accept that weighted balls are good because I said so (they probably aren’t optimal for every pitcher in every single case) – think critically about the ideas presented and make an informed decision about which training tools you want to use.

About the author

Ben Brewster is a professional pitcher in the Chicago

Want to learn more about what we know about gaining fastball velocity? Check out the wide array of blog articles we have relating to velocity building here.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

John -

Great write up Ben.

I really like the comparison to a boxer throwing a punch. A lot of people think a boxers power is about having big arms or being strong….that may help a bit, but it is really about generating a quick motion starting with the feet and hips. I like the idea of doing some heavy bag work to help teach the feeling of that whip effect working its way up the chain.

4-Ways To Improve Your External Rotation | TreadAthletics | Remote Training for Baseball Pitchers -

[…] is where constraint drills using overweight implements like Plyocare balls and wrist weights really shine. From my 2014 […]

3 New Ways to Use J-Bands for Arm Health and Velocity -

[…] balls have their place, as I’ve written about in the past, but you’ll know you’re going too heavy once a cleaner arm path starts to […]