Case Study: The Importance of In-Season Training

Written by Brice Crider

As college athletes return from their seasons to train for the summer, the importance of in-season strength training is often made incredibly apparent. Many athletes work diligently all offseason, then stop or significantly scale back on strength training during the season, and then find themselves detrained and back to square one after the season is over.

One athlete that returned to Driveline after his college season is a perfect example of this. This athlete came to us in late August of 2020 and averaged 85.9 mph during his first motion capture assessment.

We identified a few inefficiencies in his initial assessment, with a lack of scapular retraction on the throwing arm being one of the most glaring (it was 34 degrees below average when compared to our normative data on elite-level throwers). We spent the next three months aiming to improve throwing velocity with an emphasis on improving scap retraction during the throw.

During his last in-gym retest in December 2020, this same athlete averaged 90.3 mph and had gained nearly 20 degrees of scap retraction (up to 53 degrees). After his 2021 college season, this athlete came back and went through another motion capture report. Despite no significant changes in kinematic positioning from his previous motion capture report in December (he still had 53 degrees of scap retraction), this athlete’s kinematic velocities were down in every metric, and he only averaged 85.03 mph.

The lack of significant changes in the mocap report tells us that the main reasons for the decrease in velocity are likely due to factors other than changes in throwing mechanics.

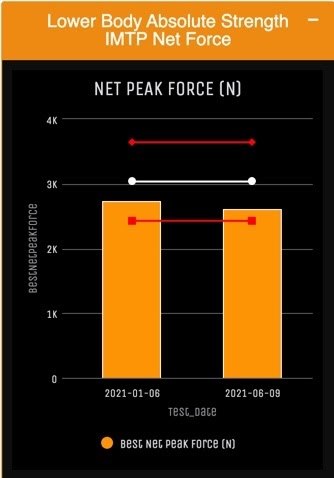

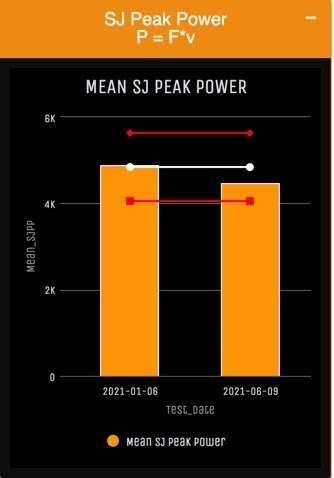

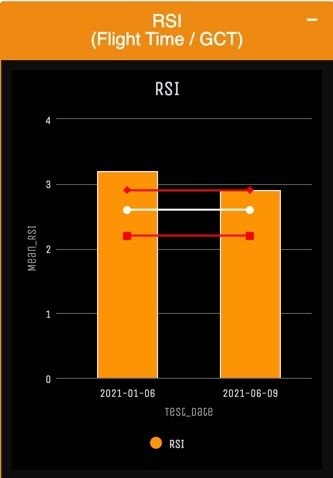

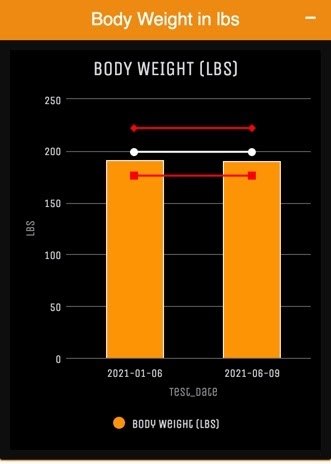

When this athlete had his strength retest, his numbers were significantly down in strength, power, and reactive strength compared to his previous retest in December, while his body weight was the same.

During his post-retest meeting to go over his mocap and strength retest results, he told us that at college he was only allowed to strength train one day per week, and that day was only one lower body strength exercise followed by mobility exercises, with a good bit of aerobic conditioning as well.

This led us to suspect that detraining during the season could be a reason for his significant losses in strength, power, and reactive strength and decreased performance on the mound.

Although some detraining and loss of off-season gains in general physical qualities may be inevitable for higher level athletes, getting significantly worse during the season is unacceptable from a high performance standpoint.

This massive detraining can leave an athlete unprepared in the playoffs when performance matters most—and completely back to the spot they previously were when they begin the offseason.

Insights for Training In-Season

When programming athletes in-season, the goal is to mitigate fatigue and prepare the athlete for competition, which means lowering volume while still giving them a healthy balance of training general adaptations.

In-season training can often be as simple as this: Give the athlete what they’re not getting on the field or in practice. Baseball players will likely be getting plenty of rotational volume and sprint volume in both practice and in the game, meaning they’ll need less of it in their training, but still need strength and power work to maintain performance.

This in-season training stimulus can vary based on the athlete’s current level; an 18-year-old high school senior should be looking to progress speed, strength, and power in-season, whereas a 25-year-old minor leaguer is unlikely to get significantly stronger or more powerful in-season because he is closer to his genetic ceiling and more stimulus would be required to reach further adaptations.

Although more adapted individuals are likely to detrain slower than their less adapted counterparts, the rule still applies: If you don’t use it, you lose it.

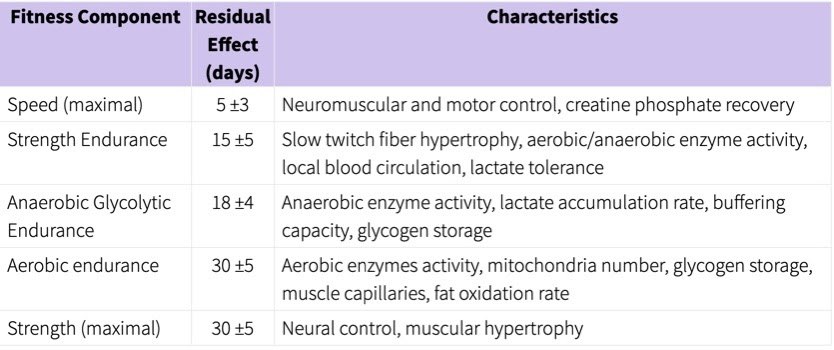

The table below provides the typical durations for the residual effects of different fitness components.

It is important to keep in mind these are general guidelines and not hard and fast rules as each athlete is an individual. Train in-season accordingly, adjusting volume based on the qualities that are likely to detrain the fastest.

Comment section