Hip Hinge, Hip Shoulder Separation, and Maintaining Spine Angle in Baseball

Because our trainers love providing both athletes and coaches access to the best resources and information, athlete education has become a priority at Driveline. Three of the concepts that we cover with all of our trainers are hip hinge in the baseball swing, hip shoulder separation, and maintaining spine angle.

Our athlete education initiatives range from classroom sessions, blog posts, and videos, to after-hours talks geared towards achieving the best results for our in-gym athletes.

In the hitting department specifically, trainers have given various talks on subjects they are passionate about. For me, I wanted to make sure that hitters had a deeper understanding of how to practice when they leave Driveline and no longer have access to the technology and coaching resources. This meant education on concepts like the intention-action model, constraints-led approach, internal vs. external focus, and practice design. Max Gordon gave presentations on hitter physical screens, interpreting kinematic sequence graphs and proper warm-up and recovery techniques.

Foundations of Hitting

30 modules teaching you everything we know about hitting and hitting mechanics.

The one thing that we did not emphasize is the thing that everyone has an interest in: visualizing important concepts in the swing!

Today, I want to introduce three S&C and biomechanical concepts that play a large role in a mechanically sound baseball swing. I am not a strength coach or a biomechanist, but learning basic movement patterns has provided me a great deal of context when working with such specialists to teach the swing. If the hitter has a basic understanding of these concepts, then they too will have more deliberate practice in the cage and the weight room. Ultimately, this will allow them to make quick adjustments in practice and when digging into the box during a live game.

The tendency is to shy away from explaining the swing in terms of basic S&C and biomechanics concepts, as the focus for the hitter shifts from external to internal, and the hitter begins thinking about the action rather than the outcome of that action. This has shown to be an ineffective mindset for performance (Wulf, Su), but there is some evidence for the benefit of setting aside time to think internally in order to learn a new move (Castaneda, Gray). From my perspective, context and information is power, and the athletes who pursue context and information in regards to their daily practice habits improve and perform better than those who do not.

A better way to put it is this: if hitters love to think about the internal mechanics of the swing and will do so regardless of what a trainer recommends, let’s at least provide them with accurate and actionable information so that they can make adjustments based on a sound understanding of those movements. This article is geared towards providing the athlete with some context for certain movements that are vital to efficient rotation and specific to the baseball swing.

The concepts we will explore are hip hinge in the baseball swing, hip shoulder separation, and maintaining spine angle. Specifically, we will discuss the how and why behind the proper execution of these moves. The goal is to educate the hitter on these concepts in order to help them train more deliberately and make adjustments at a faster rate. An external focus is key in performance, but if you don’t know what matters when you are swinging a bat and rotating, assessing yourself in real-time becomes difficult, and quality focus when it comes time for performance is fleeting.

Become the Hitter You Want To Be

Train at Driveline

Hip Hinge in the Baseball Swing

The hip hinge in the baseball swing is the same pattern found in a quality squat, deadlift, RDL, and countless other exercises. The most efficient way to execute a proper hinge is to sit back into your glutes and hamstrings and literally create a hinge separating your upper body from lower body. In a correct hinge, the pelvis is rotating rather than hinging at the lumbar spine. In other words, the glutes and hamstrings (posterior chain) are doing the work rather than the spinal erector muscles.

*This gif represents the first move of a squat. In one rep, the knees track over the toes and the movement begins from anterior chain muscles such as the quads. In the other rep, we see a well-executed hinge, as the movement begins from the pelvis and posterior chain muscles such as the hamstrings and glute maximus.

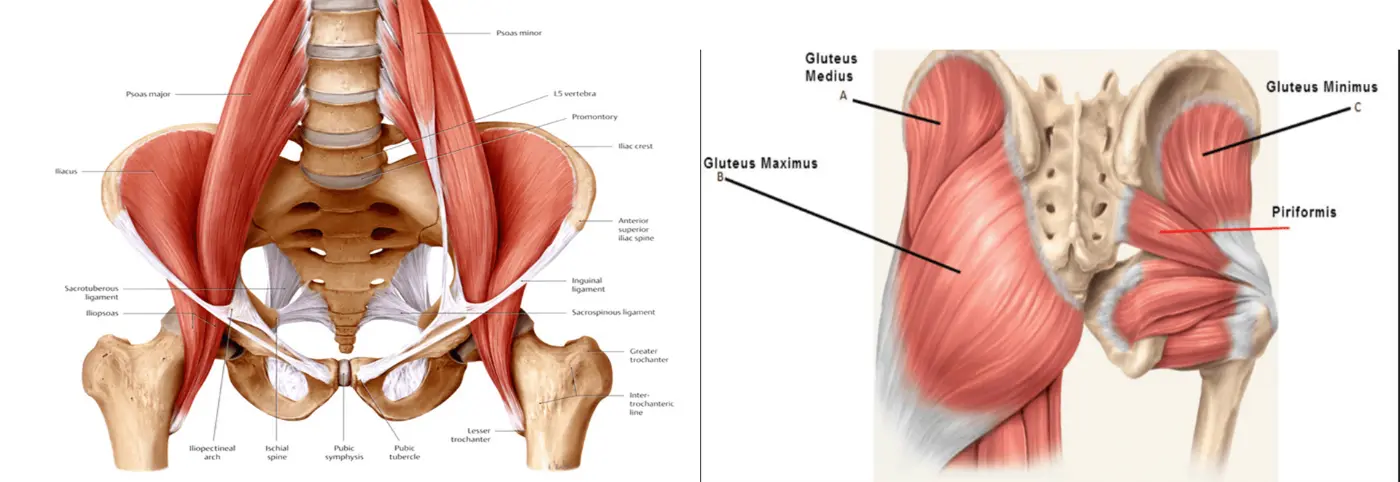

For clarity, the definition of the pelvis is the structure that connects the upper body and spine to the lower body and all of the muscles required for the motion of this structure. Described anatomically, it is the pelvic girdle and all the surrounding muscles, tendons and ligaments.

When we are describing the movement of the pelvis (flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and rotation), we are describing the movement of the pelvic girdle area.

*These images represent the basic anatomy of the pelvis. To the left is the anterior (front) and to the right is the posterior (back) view of the area.

Rotating the pelvis with a posterior dominant strategy (using glutes and hamstrings) sets the hitter in a position to transfer ground force into the bat through rotation more efficiently in comparison to extending the lumbar spine with an anterior strategy (quads). If the pelvis is not engaged with a proper hinge, the hitter will begin to shift laterally and engage the pelvis later in the swing, causing late rotation and a plethora of issues up the kinetic chain.

This pattern of posterior dominant rotation is vital to the swing, as executing it well means you have the strength to maintain posture and rotate around a stable base. This means you are engaging the muscles involved with rotation and are able to begin rotating the pelvis at the correct time. If you have an anterior dominant strategy, you lose out on the benefits of activating the posterior chain muscles and internal rotators of the pelvis such as the upper glute medius and minimus, TFL, and adductors.

Along with creating a proper hip hinge in the sagittal plane, there is an aspect of rotation that becomes relevant at this phase of the swing. The hitter will gradually gain counter-rotation up until it becomes time to make a forward move towards the ball. This counter-rotation also “loads” the pelvis and provides momentum and space for the pelvis to begin to accelerate at a faster rate than if the pelvis were minimally counter-rotated.

* This gif represents two different strategies for a hinge. In one of the swings, the knee tracks over the toes, signifying an anterior dominant strategy. The move that shows the internal rotation of the trail hip and the glutes tracking over the heels, signifies a posterior dominant hinge, which is what we are looking for in the swing.

Once the hip hinge is properly executed in the swing, the hitter is in a position to maintain the angle of the hinge and rotate around a stable base. Below are a few examples of the hip hinge and counter-rotation into the trail hip.

Hip Shoulder Separation: “X-Factor”

Once the hitter has completed the original hinge and set themselves in a good position to rotate the pelvis, pelvis rotation begins upon, or slightly before toe touch.

As the pelvis begins to rotate, a squat move creates hip flexion, seen as the hitter’s butt seems to get even more over the heels or away from the plate. This puts the hitter in a powerful position and is eccentrically loading the core muscles such as the obliques, while the torso gains a slight amount of counter-rotation (moving away from the pitcher).

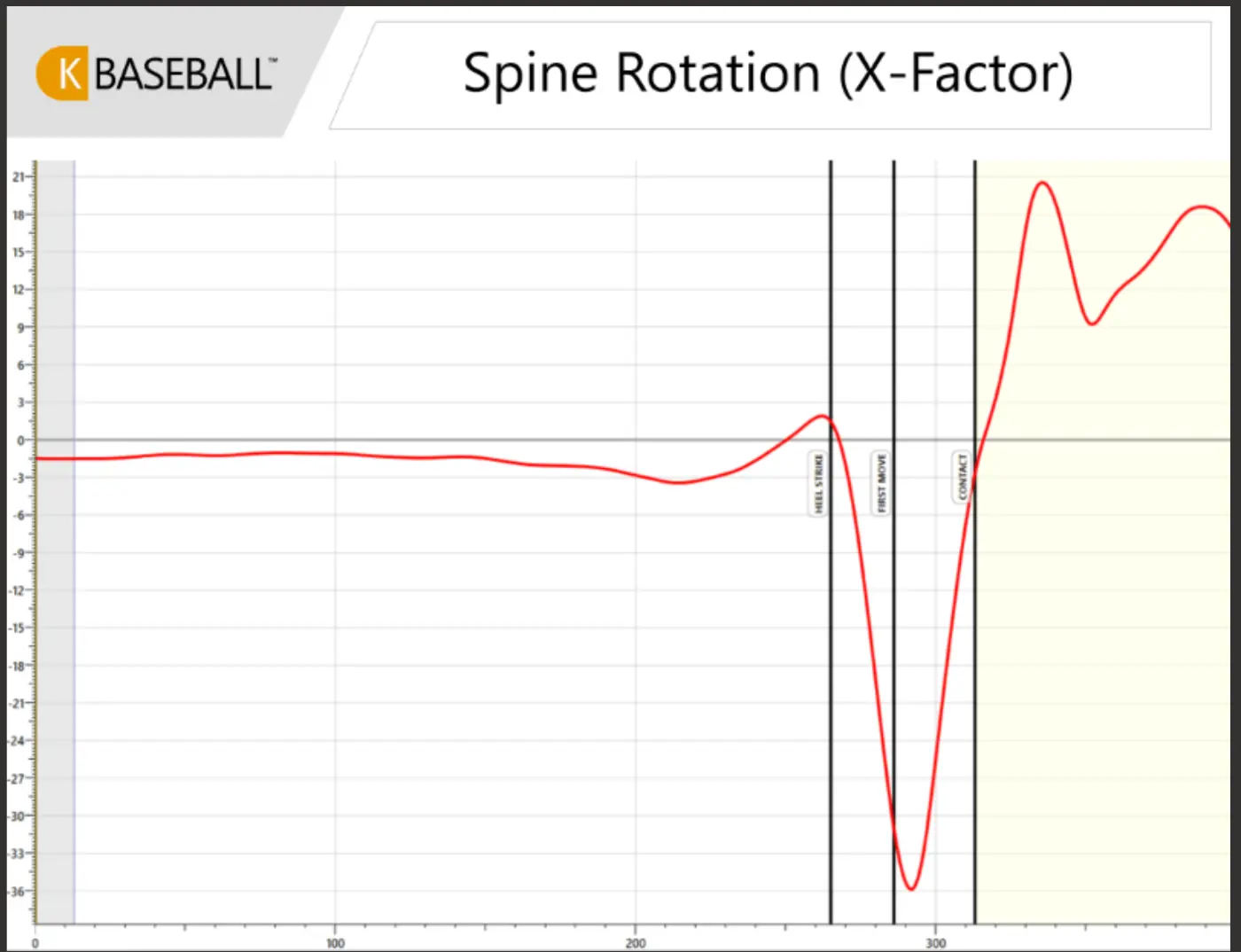

Hip shoulder separation happens in the swing when the hips begin rotating towards the pitcher while the torso gains counter-rotation. This move is extremely important in the swing and is an aspect of all mechanically efficient rotary movements such as throwing or striking. Max hip shoulder separation should occur after the first move and in alignment with the hitter’s max forward bend (see the below section on maintaining spine angle). After this point, the hips begin to decelerate and propel the torso into rotation.

*This graph from K-Vest represents hip/torso separation in the swing. The hitter reaches max separation right after first move, then the torso rapidly accelerates the torso back to neutral separation at contact.

The importance of this move lies in the loading of the core muscles. This eccentric load takes advantage of a concept called the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). In SSC, muscles eccentrically contract (stretch) and then rapidly concentrically contract (shorten) in order to produce force. This move is essential to transferring power, and the principle underlying the effect is one of Newton’s best-known laws: for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

When transferring energy through rotation, the stretching and contracting of the core muscles brings the upper body, from the rib cage up, into rotation with much more force than if the two segments (hips and torso) were to rotate at the same time and the hitter were not experiencing the “stretch” in the core. Executing hip shoulder separation correctly sets the hitter up to experience an efficient stretch shortening cycle from the torso to the shoulder, through the lead arm and eventually to the hands.

There are also intuitive hitting implications to hip shoulder separation. In order to sequence the body properly, the hips decelerate first, followed by the torso, the lead arm, and finally the hands. This means that the hands and bat are the last segments to accelerate into rotation and eventually decelerate. The hips must clear, while the torso lags behind in order to transfer energy efficiently and provide space for the hands and bat to work on plane with the pitch at the correct time.

The Baseball Swing While Maintaining Spine Angle

The hip hinge can be confusing at this point in the baseball swing, because the hitter wants to maintain the angle that the hinge creates, rather than the actual hip flexion that occurs during the hip hinge phase of the swing. This is often referred to as spine angle — or the angle of the spine in relation to the ground.

Once the hitter begins to make a forward move towards the ball and reaches max hip/torso separation a few frames after first move, the hitter then becomes “planted” and there will be no linear move with the upper or lower body until well after contact.

Generally, planted equates to the time that the hitter has reached max/hip torso separation when many hitters have most of their lead foot set on the ground. This is important to highlight for multiple reasons, with the first being hip action after pelvis rotation.

Once the pelvis begins rotating, the pelvis will also begin to extend, moving from the anterior tilt set by the original hip hinge to posterior tilt. This thrusting action is important for power (think of hip extension in a deadlift or squat), but this action alone is not enough to transfer energy to the upper body, as there are aspects of rotation and lateral flexion to consider in order to maintain spine angle.

Here is an easy way to think of this. If the first move the hitter makes is to extend with the hips and lose torso forward bend, it is equivalent to “buckling” on a good curveball, but for every pitch. In order to avoid the “buckle” and maintain posture, the hitter must couple hip extension with torso lateral flexion (side bend) and rotation. These two moves allow the hitter to maintain posture and turn through the ball with minimal loss of power when transferring energy throughout the kinetic chain.

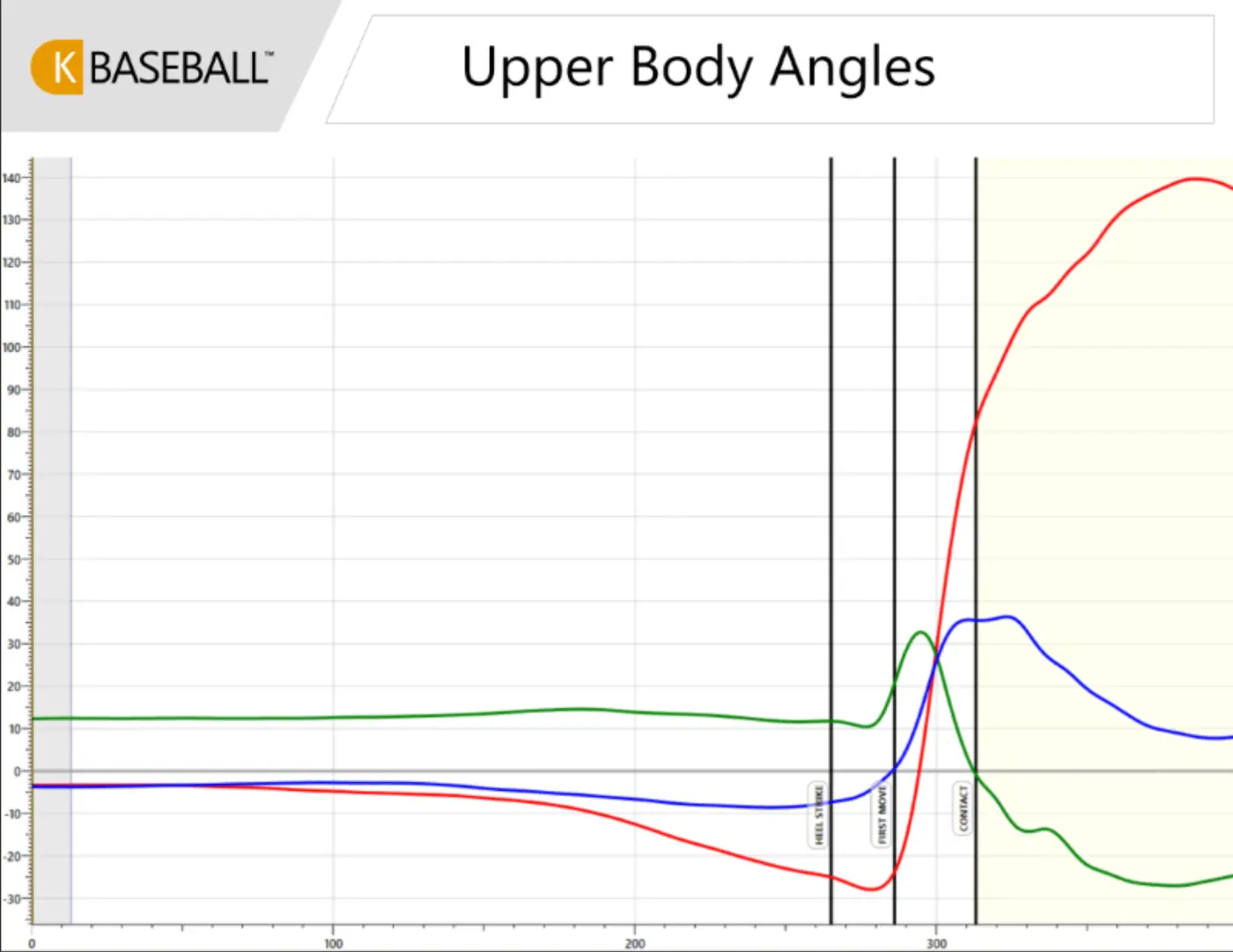

Hip Hinge in baseball can also be called “forward bend” in the swing, and this is how a K Motion graph refers to it (example above). The green line represents forward bend, the blue line represents side bend, and the red line represents rotation. In an ideal swing, forward bend, side bend and rotation will have the same value about halfway between first move (when the hands begin rotating forward) and contact.

As forward bend goes to zero (extending the hips and coming out of hinge), the hitter replaces the forward bend with torso side bend while rotating to deliver the barrel to the ball. This is what it means to maintain spine angle once the hitter’s original hinge is set.

When evaluating whether a hitter has maintained their baseball swing spine angle or not, it is important to note that this specific move should happen on most pitches in the strike zone and that many hitters will break posture to hit tough pitches. Even though this may be the case on occasion, maintaining spine angle remains an important aspect of a hitter’s approach. We often give hitters the instruction (especially with two strikes) to “not break posture” in order to assist in making quality swing decisions and take their “A” swing at pitches in the strike zone.

Top-Down Approach for Hitters

Now that we have a little more technical background on hip hinge, hip shoulder separation and maintaining spine angle as well as context for approach, let’s explore the “top-down” approach that can make maintaining spine angle immediately translate to the game.

In general, if a hitter is maintaining their baseball swing spine angle after the hip hinge phase of the swing, the value of side bend at contact will be greater than or equal to forward bend at first move (first move can also refer to when the hitter begins to extend or come out of hinge). If this is not the case, the hitter will lose posture by extending with the t-spine early. This can be signified by a head that comes up and out of the swing rather than remaining stable as the body rotates underneath.

At Driveline, we often use the “Top-Down” approach to replace forward bend with side bend.

In this approach, the hitter will set their sights on a pitch at the top of the strike zone that they can hit for an elevated line drive. This area at the top of the strike zone is the very last place in the zone that the hitter can drive the ball without losing forward bend early and have less side bend than forward bend at contact.

Here is Jason Ochart’s tweet demonstrating how we teach this approach.

At this point, the hitter will adjust to lower or more away locations by adding torso side bend and slightly more forward bend once they’ve recognized where the pitch will be. The hitter will set this angle and then begin to “rotate around the steel rod” to deliver the barrel to the ball.

It is more difficult to deliver the barrel by coming up with forward bend, lifting the head and adjusting the hands wildly to get to the ball. Which is why we coach “top-down”.

Instead, hitters can adjust to pitch type and location with larger, slowly moving segments that are easier to control, like the torso and pelvis.

Conclusion

Good hitters understand hip hinge in the baseball swing, X-Factor, and maintaining spine angle.

Another benefit to hitters and coaches of understanding these movements is that practice can become more deliberate, which in turn allows us to become more objective about how we evaluate performance for each rep, at bat or day at the plate.

A qualified strength coach can help teach these movements using basic lifts like the deadlift and squat. Hitters can internalize the movements relatively quickly—especially if they appreciate how doing so will benefit their swing.

This article introduced three high-leverage swing concepts and offered some ways to visualize them. Mastering the baseball swing includes the hip hinge in the baseball swing, correct timing of hip shoulder separation, and maintaining your spine angle are good goals for hitters to have. Understanding their importance can also allow a hitter to make adjustments more easily because that eliminates confusion as to what has physically gone wrong after a mishit.

There are few absolutes to hitting and more research needs to take place to better understand the kinematics of an elite swing. In the meantime, these three concepts can help any hitter or coach understand the essentials.

Train at Driveline

Interested in training with us? Both in-gym and remote options are available!

- Athlete Questionnaire: Fill out with this link

- Email: [email protected]

- Phone: 425-523-4030

Written by Hitting Coordinator Max Dutto

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Christopher Pringle -

That AMA from Jason was my question. I’m curious about this article and have through about and worked in these ideas for years now. What I get afraid of is teaching the same swing or comparing swings to others. I still think that hitting has so many variables that using things like k vest isn’t that simple. Pitchers easily look at rhapsido numbers and know what a pitch is doing and then manipulate themselves to be able to throw it over and over. They are the offense. Hitting is defensive where a hitter has to react to many pitches and locations and speeds. I have seen it come down to raw talent. At the highest level, you will be hard pressed to find hitters that are going to overhaul their swings. So do you assume that if a player has made it to the mlb, they check all these boxes? Or is it still random? I’m hitting I think we overlook the intangibles that are the things that matter (we overlook them because it’s near impossible to study). Timing. The eyes. The reaction time. Adjustability. I firmly believe that these are the traits that matter. Then we need to get the bat on the ball. But I think that putting movements in a box and telling players to do that will only make hitting harder. Overload/under, working out, hips and squats, plyo balls… all good stuff for hitters. Worrying about hip hinge and counter rotation, I think is hard to teach. But this week I started studying posture and how it relates to the swing. Not as a metric but as a swing cue. Look at golfers, the setup is the starting point. Hip, quads, core, back are all things discussed when you get to the basics. What if hitters did this? I rarely hear about hitters discussing engaging the core or being upright at your stance. If we can find ways to trick the mind into doing swing cues without making it confusing, we win. Sorry for the super long post and ongoing paragraph.

Driveline Baseball -

Thanks for posting your thoughts. You are spot on with hitters being on the defensive side while pitchers get to pick and choose their offensive strategy. Because of this, we have to train the whole hitter, who has solutions for all of these problems (pitch types, speeds, locations). We believe we can create better engines in our athletes, and from there we can start to work on adjustability. Variability is a high priority in all of our training. We are aslo currently investigating what hitters look at through gaze tracking. Hopefully this gives us a better idea of how to train the visual component of hitting. You also bring up a good point about setup. Check out this article that talks about posture in the swing.

Bill -

That was the best article on hitting I have ever read. I have been playing this dumb game for over 50 years. I’m a good athlete, so I never understood why my hitting was always so inconsistent. Band aid solutions would always work … until they didn’t.

I now realize my tendency is to hinge my hips the wrong way. After one swing, using the proper hinge, I felt the athleticism that I always knew was partially missing from my swing, and the balance felt perfect.

THANK YOU.