Evaluating A Swing Using K-Vest Performance Graphs

With the availability of 3D technology like K-Vest, we can now measure and see exact body positions throughout the swing—in real time. K-Vest provides a basic report that displays a hitter’s kinematic sequence and body positions at three different swing phases. This article dives deeper on what K-Vest has to offer by providing a framework for evaluating the performance graphs and the body positions associated with them.

Foundations of Hitting

30 modules teaching you everything we know about hitting and hitting mechanics.

K-Vest provides four performance graphs besides the kinematic sequencing graph. These graphs measure pelvis bend, pelvis angles, upper body angles, and x-factor throughout the swing. For interpreting the graphs, we provide numerical ranges for grouping players and relate the numbers to specific swing flaws. These ranges relate to swing mechanics, batted-ball profiles, and strike-zone heat-map characteristics. The graphs are organized from upper body to lower body and by each phase of the swing (heel strike, first move, and contact). For reference, example graphs and visuals that K-Vest provides are displayed for each graph.

This article is meant to be a reference and guide for those exploring K-Vest and other 3D devices used to measure swing kinematics. The ranges presented are general and require more data collection and validation to be presented concretely and factually. In the future, expect evidence based relationships between posture, batted-ball metrics, and other swing characteristics.

First, let’s define some key phases of the swing to help us understand general positions the body should be in and at what time. On each graph, you will notice three vertical lines. These lines represent the phases of the swing. These phases are heel strike, first move, and contact. Heel strike is marked when the pelvis reaches an angular velocity of 100 degrees per second (d/s); this is meant to show when the hitter’s foot is planted and getting close to launch position. The second line is first move, and it is marked when the hitter’s lead hand begins to rotate forward. Contact is marked when the hitter makes contact with the ball, which provides a perturbation that the sensors detect.

Become the Hitter You Want To Be

Train at Driveline

For each section, we discuss torso and pelvis bend (represented by the green line on the graphs), side bend (represented by the blue line), and rotation (red line). When measuring the angles for each body position, it is important to note that each position is relative to the ground, or horizontal. For torso and pelvis forward bend, we are looking at the movement of the torso and pelvis in the sagittal plane. Torso bend measures the amount of forward bend from above the hips to the last few vertebrae of the thoracic spine. This movement is also known as hip hinge, which is used to describe the upper body bend in exercises such as a squat or deadlift. Pelvis bend, or pelvic tilt, is the movement of the pelvis from anterior tilt (tilted up and toward the ground) to posterior tilt (tilted back to a more neutral position).

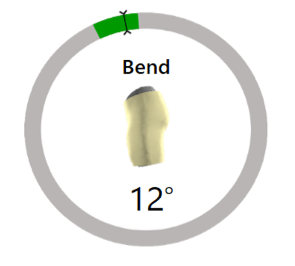

*These images that K-Vest provides in their summary report represent forward bend for both the pelvis and torso at the heel-strike phase of the swing.

Torso and pelvis bend and side bend are the angles of motion for each segment in the frontal plane. When looking at hitters, negative side bend is angled toward the pitcher (downhill) and positive side bend is angled away from the pitcher (uphill).

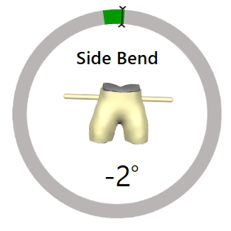

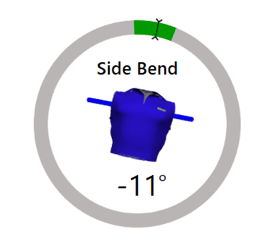

*Images represent side bend for a right-handed hitter at heel strike.

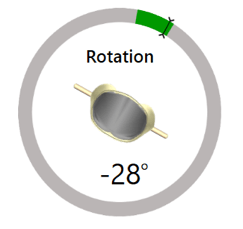

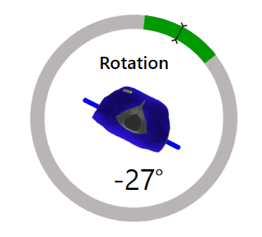

Rotation with the pelvis and torso is also measured relative to the ground with negative rotation representing counter rotation, or rotated away from the pitcher, and positive rotation represents rotating towards the pitcher as the hitter is swinging.

*Images represent counter rotation for a right-handed hitter in the negative move phase of the swing.

Torso Forward Bend (Green Line)

Heel Strike

Torso bend greater than 40 degrees is likely too bent over at the waist and under 5 degrees is too tall. On the graph, the green line spikes high on the y-axis, indicating excess forward bend. Conversely, the green line remains low on the y-axis throughout the heel strike and first move phases of the swing.

Having too much forward bend can cause a hitter to come up and out of the swing, because of the mobility and strength requirements needed to create side bend at contact that at least matches the forward bend at heel strike, or first move. (More on the relationship between forward bend and side bend later.)

Having too little forward bend can result in an inability to create lift in the swing and be on plane for low pitches. Hitters normally gain a few degrees of torso bend between heel strike and first move to set their angle on plane with the incoming pitch. On the graph, the green line hovers parallel and above, but close to, the x-axis.

First Move

The same conditions apply from heel strike to first move, but it is often beneficial to gain degrees of torso bend after heel strike. This move depends on pitch location since the hitter is setting upper-body angles in order to rotate through and deliver the barrel on the plane of the incoming pitch. On a high pitch, the hitter maintains the amount of forward bend at setup, and for a low pitch, the hitter gains a few degrees of bend in order to get on plane.

For this move, the green line spikes slightly, indicating the hitter gaining more torso bend and setting angles for the incoming pitch.

Contact

At contact, torso forward bend should be close to zero degrees at contact. The green line will appear to have crossed the x-axis at this point in the swing. Hitters will lose all of their forward torso bend by contact, and it will be replaced by positive side bend. On the graph, the green line makes a sharp descent and should intersect the x-axis at contact, representing torso bend of at or close to zero degrees. When looking at video, the torso still appears to have forward bend at contact, but in reality this is side bend of the torso.

There are a few implications with maintaining torso bend too close to contact. First, it represents a lack of hip thrust or poor timing of a hip hinge pattern. At contact, the hips and torso should intersect at the x-axis, but if the green line remains above, the hitter is not maintaining posture by replacing forward bend with side bend. Instead, the hitter is likely pulling off the ball or leaving himself susceptible to pitches away or at the top of the zone.

Torso Side Bend (Blue Line)

Heel Strike

At heel strike, the range of torso side bend is generally between 0 and -15. Hitters should be in an attacking posture and moving slightly “downhill” towards the pitcher.

Hitters who are “uphill” at this point in the swing (blue line swooping well above the x-axis) tend to hang back, which limits the ability to transfer weight to the front leg. These hitters gain little ground in the swing and also tend to “shift” their hips upon heel strike rather than immediately block with the front leg and go into rotation. These hitters are setting themselves up to “collapse,” which delays rotation, causing an arm dominant swing that can have trouble with the pitch up in the zone.

Being too far “downhill” (blue line swooping well below the x-axis) can cause noticeably late torso rotation. Hitters with excess negative bend are regularly associated with late torso rotation because it takes longer for the hitter to get back to a neutral posture (0 degrees of side bend). This can cause a push with the hands and lead arm to deliver the barrel as a compensation for late rotation.

First Move

At first move, torso side bend should fall between -5 and 10 degrees. As the hitter gets the stride foot down and initiates the swing, the side bend should be even or slightly positive.

On the graph, the green line should hover parallel to the x-axis either slightly under or over zero degrees of side bend.

Having significant negative side bend at this time means the hitter is late with rotation, and having significant positive side bend means the hitter is likely going to struggle transferring weight and is setting up to collapse with the upper half. This means that the hitter will side bend very early instead of rotating. When a hitter starts to swing, look for rotation initially and for the forward bend at first move to be eventually replaced by the side bend at contact.

Between First Move and Contact

This phase of the swing contains the main implications between forward bend and side bend.

At this point in the swing, the hitter is rotating through the ball and torso bend and side bend will have intersected with each other to become equal. As the swing progresses toward contact, side bend will begin to completely replace forward bend and forward bend will begin to descend towards zero degrees of bend.

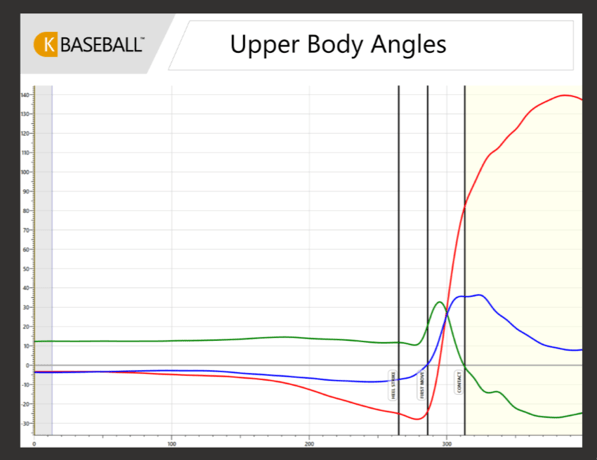

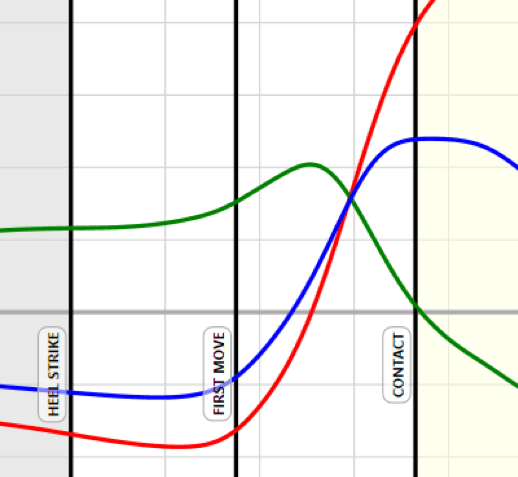

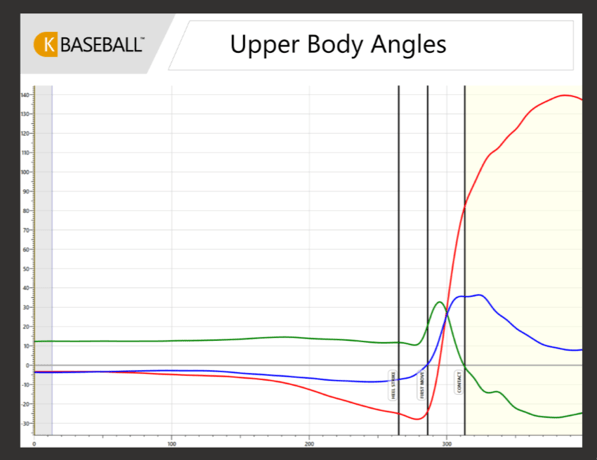

*In this example graph, we are looking at the relationship between forward bend, side bend and rotation of the torso during the actual swing. There is a clear point where forward bend, side bend and rotation lines intersect each other and this point is roughly halfway between first move and contact. This means that the hitter is maintaining their posture by replacing the forward bend with side bend and rotation.

Contact

In general, side bend at contact should be greater than or equal to forward bend at first move.

If side bend is significantly less than forward bend at first move, then the hitter is coming up and out of the swing, which means he will likely struggle to adjust to the pitch down or away in the zone. These hitters will have flatter shoulders and swing paths, rather than shoulders that appear to work underneath each other as the torso is turning. This can also explain the common coaching cue of telling hitters to work “top-down” in the strike zone, and if they feel like the pitch is taking them up and out of their posture, it is a pitch they should not swing at. For a simple visual, see Jason Ocharts, the Director of Hitting at Driveline, tweet describing posture and how it relates to adjusting for certain pitches.

When looking for torso bend and side bend at contact, the green and blue lines should appear even with each other, or at contact the blue line is slightly above the green line at first move. This is what “maintaining posture” and “replacing forward bend with side bend” means.

In this image, the first swing replaces forward bend with side bend exactly to hit the pitch up in the zone; the next swing adds side bend to adjust to the pitch down

Torso Rotation (Red Line)

Heel Strike

On the graph, we look for the red line to hover close to parallel with the x-axis and then swoop down dramatically as the swing approaches the heel strike and first move phase.

There is not necessarily a range of correct counter rotation, but in general, if a hitter possesses more than -10 degrees of torso counter rotation, we may want to add more to his game swing. The red line on the graph will hover close to parallel on the x-axis throughout the negative move phase, heel strike, and first move—if this is the case.

(Note: Be careful to distinguish tee work from live pitch when getting 3D readings because it is common to gain more torso and pelvis counter rotation off a tee.)

The implications of not having enough counter rotation are that the hitter is not entering rotation fast enough and not creating enough space to hit the pitch away or adjust when fooled. Adding more counter rotation in drills or to the hitter’s game swing can allow for quicker rotation and provide more time and ability to cover pitches away or pitches the hitter is fooled on.

If a hitter possesses around -50 degrees of counter rotation or more, the excess counter rotation can be difficult for certain hitters to control. If a hitter has an excess amount of counter rotation, there can be too much space to rotate through. This can cause the hitter to be late and the sequence to break down. On the graph, the red line descends dramatically, well under the x-axis, if this is the case.

First Move

At first move, the torso counter rotates slightly as the hips are about to enter positive rotation. This move is called “x-factor stretch” and was coined by the golf industry. This is where hip shoulder separation occurs since this move creates a load of the front shoulder (horizontal adduction) and the hitter creates a stretch between upper body and lower body to set up an efficient and powerful sequence. This move does not necessarily jump out on the graph, but look for the red line to descend slightly between heel strike and first move.

Hitters who do not have this pattern will have red lines that begin to ascend back towards the origin just at heel strike rather than gaining those few degrees of counter rotation. The implications for a lack of separation or x-factor stretch are a loss of power and adjustability since gaining the extra degrees of counter rotation in the torso as the hips begin to rotate forward can provide extra time for the hitter to read the pitch and more momentum that can result in more bat speed.

Contact

At contact, torso rotation likely should fall between 70 and 90-95 degrees. At this point in the swing, the torso has decelerated and should be transferring energy from the lead arm to the hand and eventually to the barrel. On the graph, the red line falls on the middle of the y-axis.

Between 70 and 95 degrees is a considerable range of motion to fall into, and this is due to the likely strong relationship between the amount of torso rotation at contact and location of the pitch. It makes intuitive sense that for an outside pitch, the hitter would rotate less, and for the inside pitch, the hitter would want to rotate a little bit more to deliver the barrel.

Anything past 95 degrees can be considered over rotation. This normally translates to pulling off the ball and late torso speeds in general. These hitters have trouble decelerating the upper body in order to transfer energy from the middle of the body to the hands and bat. On the graph, over rotation is visible when red line spikes high up on the x-axis.

Rotation under 70 degrees can generally be considered under rotation. This is likely due to late hip and torso acceleration and is associated with push, hand-dominant swings. If the hitter is under rotated at contact on the graph, the red line falls very low on the y-axis to indicate under rotation.

This in-gym hitter has rotated his torso fully (appears to be 90 degrees in relation to the ground) in order to hit this ball flush off of the machine.

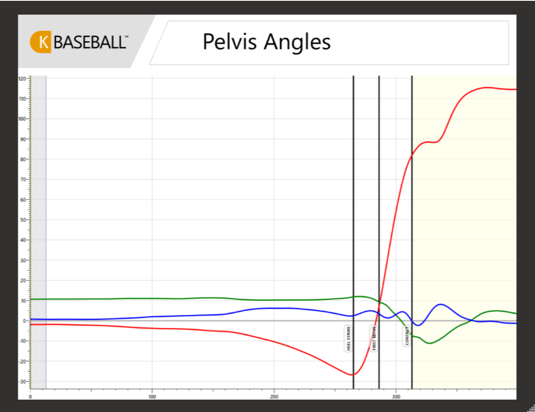

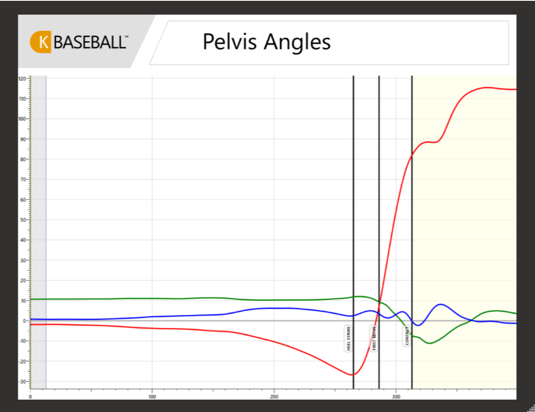

Pelvis Forward Bend (Green)

This graph measures pelvic tilt and how the pelvis thrusts throughout the swing. At the start of the swing, the pelvis starts in anterior tilt (positive bend) and at contact, ends in posterior tilt (negative bend).

Heel Strike

At this point in the swing, the hitter will set the angle of his torso and pelvis bend as he is reading the incoming pitch. It is common for the pelvis to fluctuate a few degrees up and down before heel strike while the hitter is striding and loading his body. But at heel strike, or a few frames after, the angle of bend is set. At this point, the pelvis should be between 10 and 40 degrees of pelvic bend. It is much more common to see excess bend (excess anterior tilt) than too little bend.

Hitters who fluctuate excessively, or who have excess pelvic bend, are normally not great candidates for a leg lift because having excess anterior tilt can be associated with limited hip internal rotation. Hitters who struggle with internal rotation and have pronounced pelvic tilt tend to struggle with loading their back hips dynamically in the form of a large leg lift.

First Move

In the first move phase of the swing, the pelvis normally gains a few degrees of bend between heel strike and first move but rapidly begins to thrust between first move and contact. These are the same implications of torso bend where the pelvis is supporting the torso in setting angles for the incoming pitch. On the graph, the green line spikes slightly between heel strike and first move and then begins a rapid descent into thrust.

It is common for hitters to be late in their hip thrust, so we are looking for at least some type of positive to negative bend at contact. Late hip thrust or no hip thrust (no move into negative bend) can cause hitters to pull off the ball and have poor swing direction (think of an “ass out” swing). Hip thrust (hip extension) is also a great indication of rotational power since it is common to see hitters or powerful golfers come up onto their toes through hip extension at contact. Coming up onto the toes is product of powerful hip thrust rather than a shift of weight to the front side of the body.

Contact

In golf, it is common to look for “reciprocal” hip thrust. This means that if the hitter starts with 10 degrees of pelvic bend, at contact the hitter will be at -10 degrees of bend. It is unclear whether this is a standard component of evaluating hip thrust in the baseball swing, but in general, look for correct timing of hip thrust and move from positive (anterior) to negative (posterior) bend.

Pelvis Side Bend (Blue)

Heel Strike

Pelvis side bend is similar to torso side bend in that it is used to determine whether the hitter is “uphill” or “downhill” at heel strike. Generally, the pelvis remains closer to neutral than the torso with the blue line hovering around the x-axis. A solid range for a hitter to be in is between -8 and 8 degrees of pelvis side bend.

If a hitter has too much positive side bend (blue line swooping well over the x-axis), the hitter is setting up for an uphill swing. These hitters will likely be hanging back and having trouble transferring weight to the front leg.

If a hitter has excess negative bend (blue line swooping well below the x-axis), then the hitter is starting his swing too far downhill and will be late going into rotation. Again, the implications are similar to torso side bend, where too much negative bend at the wrong time can cause late rotation and an inability to hit the ball deep with any authority.

First Move

Pelvis side bend at first move has similar implications to side bend at heel strike. We look for excess bend in either direction to determine if a hitter is starting too far up or downhill.

At this phase of the swing, we can begin to think of the pelvis as a stable base for the torso to adjust and rotate around. At first move, the hips should have begun to open as the torso gains more counter rotation and the hitter reads the pitch. The adjustments to location will then be made by torso bend, side bend, and rotation, with the pelvis acting as a stable base to support torso action.

Contact

At contact, pelvis side bend differs from torso side bend since the pelvis should remain relatively neutral at contact (blue line along the x-axis). These are the same implications with heel strike and first move. The hitter should be in positive side bend to support the side bend of the torso.

The amount of bend at contact may depend on pitch height and location but not to the degree of torso side bend. We are still looking for excess bend in either direction to determine if the hitter is collapsing and is generally between 5-20 degrees of positive side bend of the pelvis.

Pelvis Rotation (Red)

Heel Strike

Pelvis rotation is similar to torso rotation in that there is not a set range of counter rotation we are looking for. In general, if the hitter has -10 degrees of counter rotation, or a number closer to zero, then it is worth exploring gaining more counter rotation at heel strike. In a pelvis angle graph that contains little counter rotation, the red line remains under, but noticeably close to the x-axis.

The implications of too little counter rotation is a hitter who lacks momentum leading into low peak speeds or late rotation. This can cause the hitter to not have enough time or momentum to read the pitch and can struggle with pitches away or pitches he is fooled on.

*In the example graph, the pelvis gradually gains counter rotation, then rapidly accelerates into rotation to initiate the swing.

In evaluating a hitter that possesses excess counter rotation, -50 degrees of counter rotation or below is likely too much counter rotation at heel strike. On the graph, the red line swoops well under the x-axis, indicating a great deal of torso counter rotation.

The implications of too much counter rotation is a hitter who is late going into rotation and therefore must compensate with early peak speeds with the lead arm and hand. Also, excess counter rotation with the hips tends to mean less counter rotation with the torso. (More on this relationship when we explore hip/shoulder separation.)

First Move

At first move, the pelvis will begin disassociating from the upper body and get close to positive degrees of rotation. The timing of this rotation plays a significant role in creating an efficient sequence and maximum power. (Again, more on this when discussing the x-factor graph.)

Contact

The pelvis rotates similarly to the torso at the contact point in the swing. The hips should be rotated between 80 and 90 degrees at contact, indicating correct deceleration patterns and swing direction.

If the pelvis is over-rotated (over 90 degrees), this can indicate poor hip action and late deceleration in the swing. This could indicate a “soft” lead-leg block where the hitter drifts past the hips’ peak speed, or deceleration point, instead of sharply decelerating and transferring energy up the chain. On the graph, the red line shoots up noticeably high on the y-axis at contact, indicating over rotation.

If the pelvis is under-rotated, this could lead to inefficient sequencing, causing a pushy, hand dominant swing. This is a pattern that is taught at young ages where coaches preach that the torso and hips stay closed throughout the swing. On the graph, the red line falls low on the y-axis at contact, indicating an under rotated swing.

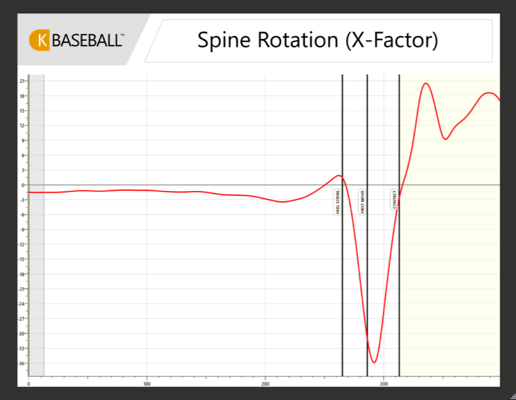

X-Factor (Red)

X-factor is the term used in golf for hip-shoulder separation. Hip-shoulder separation is necessary for an efficient sequence and maximum power. The x-factor graph represents the torso and pelvis in degrees of separation. Negative x-factor represents more counter rotation with the torso (red line below the x-axis), and positive x-factor (red line above the x-axis) represents more counter rotation with the hips.

Pre-Heel Strike

In the negative move, or gather phase, of the swing, the hips and shoulders should enter counter rotation together. This means that if the torso is counter rotated -20 degrees, then the pelvis should be close to -20 degrees of counter rotation as well. This is represented on the graph as the red line hovering under, but very close to, the x-axis in the negative move phase of the swing. This means there is close to zero degrees of separation.

It is common for hitters to have a red line that hovers well below the x-axis at this point, and the degrees of separation should be monitored (under -30 degrees of separation can be considered alarming). Conversely, excessive positive separation in the negative move is also a cause for concern. This is indicated by the red line hovering well above the x-axis. This characteristic can lead to timing issues, in which the shoulders must rapidly gain more counter rotation or the hips must rapidly go into rotation to achieve enough hip shoulder separation to create power.

First Move

First move is the “x-factor stretch” portion of the swing. It is common to achieve zero degrees or a little positive separation at this point, but the main aspect to look for is a rapid descent of the red line between first move and contact. This represents a large stretch between the pelvis and the torso, setting up an efficient sequence and maximum power.

It is important to distinguish the proper amount and timing of x-factor stretch. Ideally, the peak point of separation occurs at or around first move and the red line makes a massive jump back towards the x-axis. If the stretch occurs too late, this indicates poor timing of x-factor that can possibly lead to inconsistencies in contact ability and adjustability. Too much separation (-50 degrees and below) can be alarming, especially if the hitter has previously demonstrated poor body control or contact ability.

If the hitter displays too little separation, the graph indicates a red line that is too close to the x-axis at first move and before the ascent into rotation. Too little separation can set up a hitter to rotate poorly since the hitter likely has not loaded the lead shoulder properly with an x-factor stretch move. This can lead to a pushy and hand-dominant swing.

Contact

At contact, the pelvis and torso should be achieving the same degrees of rotation, ideally with zero degrees of separation at contact. This indicates a very efficient swing and deceleration patterns since the torso must rapidly catch up to speed as the hips lead the way and decelerate. On the graph, the red line appears to cross the x-axis at contact, or close to it.

Offset separation (either the pelvis or torso, rotated excessively compared to the other segment) at contact can indicate some disconnect throughout the swing, resulting in over rotation and poor deceleration patterns. More commonly, disconnect means over rotation in the torso rather than too much hip rotation and negative separation at contact. The torso is more likely to over rotate because of poor hip action and deceleration resulting in “drift” of both segments. Look for excess positive separation at contact (red line high up on the x-axis) for over rotation of the torso.

Conclusion and Using K-Vest to Train Hitters

K-Vest and 3D devices of the like have provided a platform to measure the swing in motion with reasonable precision and in real time. The ability to do so is an extremely new concept to the world of training baseball hitters, and the information provided in this article serves as a more in-depth introduction to the use of such devices in analyzing the kinematics of a hitter’s swing in relation to batted ball and other swing characteristics.

As always, more data and research is needed to validate the general ranges provided. In the future, marker and markerless motion capture will help provide more concise data on kinematics and kinetics of the swing. Expect blogs like our Blast and HitTrax contentions, as collecting data on K-Vest and the metrics it provides is currently not very accessible, but will be a possibility in the near future.

The exciting aspect about mobile devices, such as K-Vest, is that they can be used as feedback for the hitter in a matter of seconds. The ability to employ biofeedback is huge for developing the way we train hitters and develop more efficient movement patterns. We currently employ the technology in our swing-design sessions, where we work with hitters one on one to develop new patterns and provide an opportunity to think internally about their swings. Biofeedback speeds up this process by allowing each hitter to pair a feel to an exact measurement as fast as using feedback from a launch monitor. An example of this is working on hip-shoulder separation at first move. If the hitter is having trouble clearing his hips in time to create maximum hip-shoulder separation at this point in the swing, K-Vest can provide the exact measurement of degrees of separation and pelvis rotation first move. The hitter then has instant context for his feel and can pattern a movement at a much quicker pace.

For this article, the goal is to understand the graphs and posture in the swing in great detail in order to use biofeedback and 3D devices such as K-Vest effectively. As a coach or player, providing feedback and context at the right times can rapidly increase the learning process and ultimately improve game-time performance.

Conclusion and Using K-Vest to Train Hitters

Interested in training with us? Both in-gym and remote options are available!

- Athlete Questionnaire: Fill out with this link

- Email: support@drivelinebaseball.com

- Phone: 425-523-4030

Written by Hitting Coordinator Max Dutto

Comment section