Releasing Tommy John’s Grip on Pitchers

It’s about that time, isn’t it? The short period of time where we notice the rash of Tommy John surgeries and shoulder injuries to pitchers and look for answers in the usual places, like Tom Verducci’s columns (never mind that the Verducci Effect has been thoroughly debunked) where the “experts” are interviewed and say some variation on the following:

- Travel ball is evil

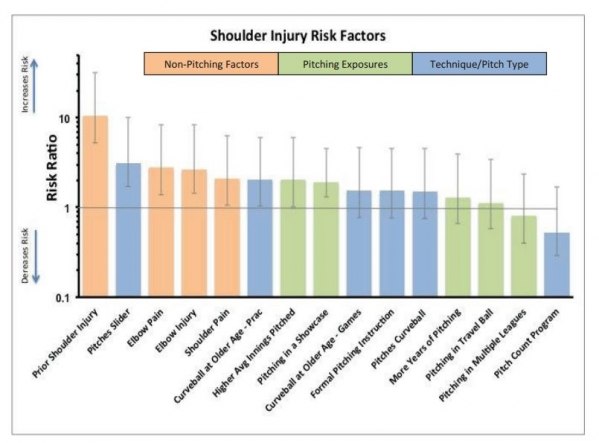

- Showcase ball will cause you to kill your arm, damn those people at Perfect Game

- Latin players grow into their velocity

- Americans put too much focus on velocity

- etc

Let’s not forget: If a pitcher is going to be injured, it is most likely at the beginning of the year. The reasons for this aren’t necessarily clear, but as Dirk Hayhurst pointed out in his latest book, when he hurt his shoulder in the gym, he was tempted to nurse it to the beginning of Spring Training and hope to blow it out on the mound there so medical insurance would be picked up by the team. It is not inconceivable that this is a significant contributor. Additionally, players are often allowed to do whatever they want in the offseason by their teams, and are not given specific workouts to train their arm. I’ll always remember Matt Diaz doing P90x in the 2008-2009 offseason, which is probably one of the worst possible “training” (I use the term loosely) methods you can employ for a baseball player. A lack of a sound throwing program with specific prehab exercises probably contributes to both the velocity drop at the beginning of the year (in addition to weather of course) as well as increased risk of injury in the early months of the year.

So, with all that out of the way, let’s cover some major talking points in the Great Tommy John Debate.

Youth Pitchers are Overused

This is a trope that generally covers the “showcase baseball is more risky than Little League” as well as the “pitch counts / adequate rest is important” line of argumentation. Most of these arguments lately are based off of a longitudinal 2011 study done by the University of North Carolina (pdf, web) which indirectly surveyed youth, high school, and college pitchers across the country from 2006-2010 (HS players 2007-2010, college players 2008-2010).

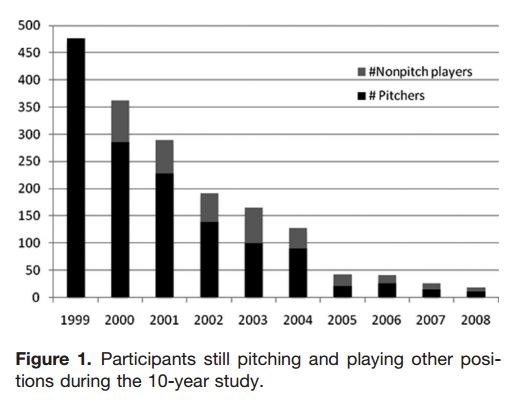

ASMI also released a ten-year longitudinal study (pdf) in 2006 that concluded that pitching more than 100 innings in a calendar year increased the risk of serious injury to the pitching arm. However, like most longitudinal studies, sample size and retention rate dropped off very quickly:

The University of North Carolina study was cited by many publications, including USA Today, which concluded:

The study found the primary cause of such injuries is overuse.

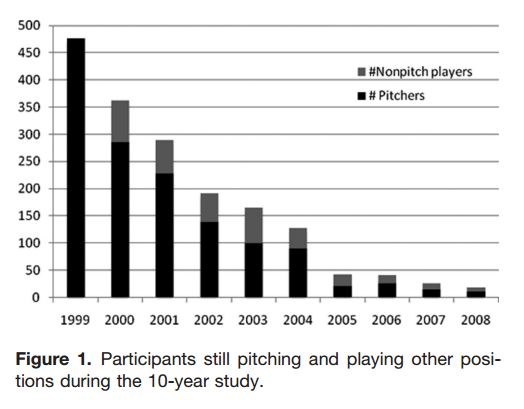

Researchers went on to say that curve balls were not more likely to hurt a pitcher’s elbow than any other type of pitch based on the data from this study. Fortunately, they published their summarized data for review:

Er… overuse is the primary injury factor here? Like Russell Carleton concluded based on statistical analysis of MLB pitchers, it’s actually prior injury that best predicts future injury. And furthermore, the second-highest risk ratio was throwing sliders, according to the data! Higher innings pitched and showcase pitching both fall below use of the slider AND the curveball (thrown at a later age).

Now, pitch counts seem to be effective at reducing injuries to youth athletes, and that’s certainly a cause I can get behind. It is my opinion that pitch counts need to be instituted at the youth level to avoid abuse by parents, even if these pitch counts are overly conservative.

So, is overuse a real problem? I have no doubt that some coaches and parents out there abuse their kids by leaving them in games too often. However, the 30th pitch of the inning and the 30th pitch of the game in the third inning aren’t the same stress-wise, and this is a factor that should hopefully be understood by coaches and parents alike.

But outright blaming showcases and select teams for the rise in pitching injuries is irresponsible, considering none of these studies controlled for the ability of the pitchers in question – of course the pitchers who throw hard and are more effective tend to do more showcases, and this effect can be very large.

Which brings us to our next point…

Kids Throw too Hard

In Tom Verducci’s latest article in Sports Illustrated, he talks at length about how youth pitchers are overused and how velocity is at a premium, which leads to more injuries to the pitching arm and a rising number of Tommy John surgeries. He quoted an anonymous international scouting director, who said:

Latin American pitchers are allowed to grow into their velocity. It’s a common story to sign a guy throwing 84, 85 [mph] who eventually winds up throwing in the 90s. Michael Pineda is one. You’re looking for someone with a good, athletic body who can throw the ball around the plate and has a feel for spinning the ball. The velocity comes in time, with training and better nutrition and physical growth. Here? The statistics don’t lie. We need to look elsewhere around the world to learn a better way. It’s time.

Really? The same Michael Pineda who missed three months in the minors during the 2009 season with a non-specific elbow injury and later had invasive labrum reconstruction surgery, requiring him to miss all of 2012 and most of 2013? The same Michael Pineda who averaged just about 95 MPH with the Seattle Mariners and has now “grown into” an average velocity of 92.5 MPH with the Yankees?

Verducci continues the cherry-picking, noting:

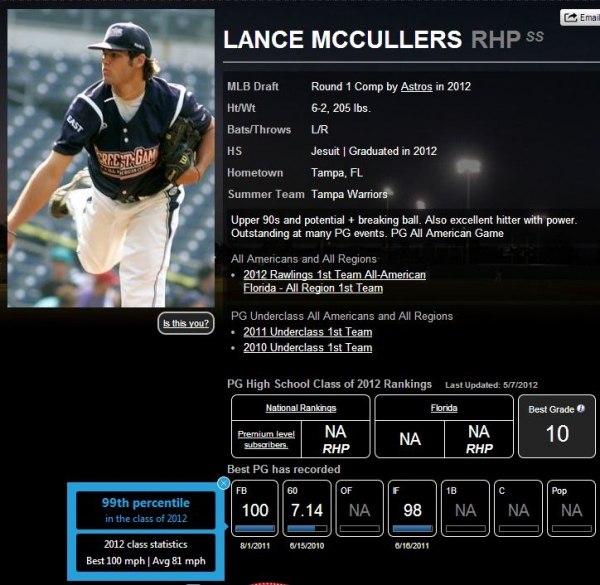

Go back to 2002, which featured a strong first-round high school draft class that included Zack Greinke, Cole Hamels and Matt Cain. None threw harder than 94 mph as seniors. All of them have thrown more than 1,500 innings in the big leagues.

Greinke never threw harder than 94 MPH as a senior? Perfect Game shows he threw 94 MPH during the winter after his junior year of high school, and John Sickels noted something entirely different in his ESPN column during the 2003 summer season:

Greinke is an excellent overall athlete, who was mostly a position player before his senior year in high school. He moved to the mound full-time a few months before the ’02 draft, and showed stunningly quick development. Greinke’s fastball has been clocked as high as 96 mph, though it’s more usually in the 90-93 mph range. He hits spots with it, and isn’t afraid to throw inside. His curveball and changeup are already above-average pitches.

Hamels broke his humerus bone his junior year of high school, which limited his velocity and dropped his draft stock to the middle of the first round. So even if he was topping out at 94 MPH, there would have been extenuating circumstances on why he didn’t throw harder considering he missed an entire year of development. But Verducci was verifiably wrong once again according to mlb.com:

Hamels returned to go 10-0 with an 0.39 ERA his senior season, impressing the Phillies with his 94-96 mph fastball and plus curve and change.

By the way, all the experts that say playing multiple sports is good for an athlete may enjoy this bit of anecdotal fun:

Apparently the 18-year-old would run through a truck to play for the Phillies — a parked car to be exact. Hamels smacked into the back of one playing street football with friends. He injured his arm then but did nothing about it. Three weeks later, he broke the humerus bone in his throwing arm while pitching in a game.

(I happen to think playing multiple sports is a good thing, too – but for psychological reasons and not “scientific” ones that are trotted out there all the time.)

Matt Cain did not, in fact, throw over 94 MPH as a high school senior – reportedly topping out at 92 MPH. However, once he was allowed to “grow into” his velocity in professional baseball, he fractured his elbow while pitching in 2003, just one year after the draft.

Jonah Keri’s post on the topic at Grantland started off a bit more realistic, quoting some solid research presented by Dr. James Andrews:

“The big risk factor is year-round baseball,” Andrews said. “These kids are not just throwing year-round, they’re competing year-round, and they don’t have any time for recovery. And of course the showcases where they’re pitching for scouts, they try to overpitch, and they get hurt.”

I can’t disagree with that – playing games and pitching competitively year-round is ridiculous and should be immediately stopped. I advise all of my warm weather clients to tell their winter ball coaches to kindly stuff it while they rest, recover, and train hard in the weight room or play a second sport.

But then Jonah quotes another anonymous AL executive who seems to be totally clueless about cause and effect:

“The rise of Perfect Game baseball and other summer travel baseball has dramatically decreased the off time for younger players. Kids are traveling all over the country from 8 years old on, and playing year-round. Colleges are recruiting younger and younger, and kids feel like if they don’t compete in every summer or fall event, they will lose their chance for exposure. That kind of exposure also leads to kids absolutely airing it out at max effort. When the section behind the plate is loaded with recruiters and scouts, kids absolutely take it up a notch and try to throw it through the backstop. The damage that is being done early can’t be undone by managing workloads once pitchers get into pro baseball.”

So… how is this Perfect Game’s fault, exactly? College and professional teams are the ones sending scouts to these events! If they were so concerned with keeping kids healthy, they would decrease the incentive to attend the events by not sending representatives of their teams. PG is only responding to market forces by providing events, and it’s a stretch to blame them specifically for decreasing the amount of time off, anyway.

Dr. Andrews goes on to say:

“It used to be that we didn’t see these injuries until they got into high-level professional baseball. But now, the majority of the injuries are either freshmen in college, or even some young kid in ninth, 10th, 11th, 12th grade in high school. These young kids are developing their bodies so quickly, and their ligament … isn’t strong enough to keep up with their body, and they’re tearing it.”

It’s true that the majority of the injuries happen early in the year as well as early in a pitcher’s developmental cycle, but to say that it’s wholly because their bodies are developing so fast ignores a whole host of other variables we’ll get to later in this article – such as massive ignorance of training principles amongst amateur baseball coaches.

Dan Jennings – GM of the Miami Marlins – said:

“Back in the day, you’d be pitching melons in a field, doing things with your hands — that’s how you built strength, from your elbows to your fingertips. Because of the new strength and conditioning programs, that’s been taken out. By the 10th grade, you’re told to focus only on football, or only on baseball; kids no longer play multiple sports. You get these specialized regimens where you build large muscle groups, but not the small muscles around the rotator and UCL. The large muscles get developed so large that when you try to decelerate, you can get badly hurt.”

Of course, Jonah interviewed a strength and conditioning expert in the field of baseball like Eric Cressey, Ron Wolforth, or if those two were busy, maybe me, right? No. Not a single interview appears in the article with an athletic trainer that is well-known for training amateur players with a good record of health like the aforementioned people I listed. I highly doubt we were all so busy we couldn’t be reached via email or phone call – I know that I didn’t get pinged before this article went up!

Our field got thrown further under the bus with no chance for rebuttal by an anonymous executive, who said:

“I think what has happened is that, due to improved training and instruction, pitchers throw harder. Joints and related connective tissue are put under greater stress from the increased velocity. Many claim that they can reduce injury with ‘their program.’ There is no evidence to support those claims. I am afraid, in fact, that many of these programs — several of which are well designed — actually increase injuries. The conundrum is that they also improve performance.”

First of all, this is a completely ridiculous statement with no evidence presented in favor of it – unfortunate, consider Jonah Keri used to write for Baseball Prospectus, a website that highly values falsifiability and thorough research.

Secondly, I have done internal studies on our training program of our amateur and professional talent, and when comparing our data with longitudinal studies and surveys done at appropriately matched levels, Driveline Baseball athletes are far less likely (2+ SD) to suffer a major arm injury (defined as missing competitive baseball for 8+ weeks; usually surgery) than your average athlete. I am sure that the athletes at Cressey Performance training under Eric Cressey and Matt Blake have similar – if not better! – records at keeping their athletes healthy, yet at least I was not contacted to give my side of the story, and I highly doubt Eric or Matt passed up on a chance to chime in with their experiences on such an important subject matter.

Let me take a moment to state that at Driveline Baseball, injury prevention is the NUMBER ONE most important lens that all training is filtered through. Our private training facility has some of the most sophisticated equipment you can possibly find, and I can absolutely guarantee you that no other private pitching development facility in the world has the scientific tools we have to evaluate pitchers.

We use multiple high-speed cameras in a markerless biomechanics laboratory that can calculate both kinematics and joint kinetics, a four-camera synchronized system to subjectively evaluate pitching mechanics, a database of major league pitchers with correlated planar kinematics and injury histories to compare our pitchers to, wearable athletic EMG sensors to measure muscle activity under the skin during maximum effort throwing with no degradation in performance/velocity, and force plates to measure ground reaction forces of various activities – not to mention high-end EMS recovery tools like the Marc Pro and custom-manufactured and designed implements like Driveline Plyo Ball ®. All of that to prevent as best we can our athletes sustaining Tommy John surgery.

So while I can’t speak for others (though I have a good feeling that the aforementioned people care a LOT about preventing injuries), I am doing a whole hell of a lot to analyze and study the pitching delivery to help cut down on injuries to our pitchers, and I don’t really appreciate the blanket statement handed out by baseball executives hiding behind an anonymous snippet throwing the strength and conditioning community under the bus like we’re a bunch of idiots who don’t care about the future health of our clients. Furthermore, it’s quite irresponsible of Jonah Keri to not get this side of the story from noted representatives of our field, a fact I have pointed out on Twitter which garnered no response.

The real problem is probably a bit more involved, but what’s clear is that teams are not electing to draft weak arms and hope to develop them – they still go for the hardest throwers possible in the top rounds. Of course, they’re absolutely correct to do so, considering that fastball velocity is the number one best predictor of strikeout rate and success at the MLB level:

Being able to bring the heat is a very important factor in a pitcher’s success. Being able to crank it up a notch typically improves a pitcher’s run prevention abilities, and losing a notch hurts his effectiveness. Starting pitchers improve by about one run allowed per nine innings for every gain of 4 mph, and relief pitchers improve by about one run per nine innings for every gain of 2.5 mph.

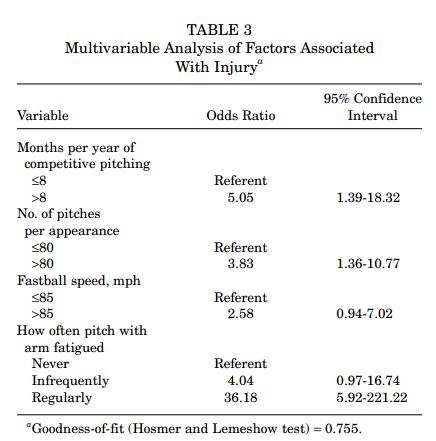

ASMI’s Risk Factors for Shoulder and Elbow Injuries in Adolescent Baseball Pitchers (Olsen, Fleisig, et al AJSM 2006) was heavily cited in Verducci’s article to damn fastball velocity. The study had numerous flaws, including self-reporting of injury factors for control groups and injured groups (groups who are hurt are FAR more likely to report negative things about their coaches and previous throwing programs, and this factor was not controlled for) but was still a mostly well-designed study with very interesting data. Using a multivariate analysis of the data yielded far more interesting conclusions than the cherry-picked conclusions from the abstract:

So despite the fact that Verducci (and Fleisig, to a lesser extent) blamed fastball velocity as a huge factor, it is actually in fact the least important factor in the multivariate analysis. And where did the 85+ MPH marker come from? It seems to have been subjectively chosen as a “high-velocity” marker.

Regardless of the origin of the “velocity limit,” if we simply accept the number given, throwing harder is fourteen times less relevant to predicting injury than pitching with arm fatigue on a regular basis, and half as relevant as pitching year-round (greater than 8+ months per year, a good number considering winter ball is the usual culprit here).

Uneducated, Ignorant, and Malicious Coaches are the Real Problem

If you play baseball, let me ask you a question: What would your pitching coach say if you asked him to cite his favorite research paper on pitching injuries?

Let me guess: Nothing. Or you’d be benched.

This is the real problem. Coaches at all levels simply don’t care about educating themselves on thrilling topics such as kinesiology, biomechanics, and research. The gold standard for coaching at higher levels of baseball is the fact that the coach played professionally or at a high college level, as if this is some good way to evaluate someone who will have a large role in keeping your arm healthy. It is, of course, the best example of falsely appealing to authority.

Let’s just pick a random well-known article on baseball pitching that is fairly important, such as Comparison of shoulder range of motion, strength, and playing time in uninjured high school baseball pitchers who reside in warm- and cold-weather climates (web). This paper by Kaplan, Elattrache, et al (AJSM 2011) talks about the soft tissue differences in pitchers who reside in warm weather climates compared to cold weather climates, concluding that athletes who competitively pitch year-round in warmer climates tend to have increased shoulder range of motion (ROM) and poorer shoulder external rotation strength. It’s fairly basic stuff to most decent trainers and coaches out there, but even a concept like this requires a coach to:

- Read the paper

- Understand the implications for increased total ROM of the throwing shoulder (perhaps GIRD?) and decreased ER strength (deceleration weaknesses?)

- Figure out the best ways to counter these negative adaptations (specific stretching? passive external rotation strengthening? more time off?)

- Deploy it effectively with his pitchers

- Monitor the changes in soft tissues and ranges of motion

- Evaluate his corrective exercise program and follow up with improvements

Keep in mind that this is for a SINGLE well-understood adaptation that happens with throwers of all ages and has wide-ranging implications on keeping arms healthy (let’s not even get into the elbow, hips, core, etc), and understand that the vast majority of pitching coaches (95%+?) don’t even do this. Your average pitching coach has never heard of Eric Cressey, Ron Wolforth, Lee Fiocchi, Matt Blake, Randy Sullivan, Jim Wagner, Kyle Boddy, or any other progressive baseball coach out there who cares about sports science, and expecting the average 14 year old to keep up on graduate-level kinesiology isn’t exactly fair.

Anti-Intellectualism is the Real Issue

Of course, this is nothing new in America – the dislike for intellectual behavior is well-established in this country and is perhaps most strongly present in the sports world. Consider how long it took Bill James and Pete Palmer to have their ideas adopted by most of professional baseball and you will come to the stark – and sad – realization that true player development (and injury prevention) is even further behind today than where James and Palmer started decades ago.

Since amateur coaches aren’t going to reverse their trend any time soon, it is unfortunately up to the athlete and parent in question to educate themselves and to fight back against disruptive and dangerous behavior by baseball coaches at large. Coaches that do not understand kinesiology and the importance of a proper training and throwing program must have kids taken out from under their wing; parents (and kids, sadly) must stand up to them and refuse to let their arms be abused, even if it means being labeled “uncoachable.”

Stop blaming velocity, pitch counts, and other weakly relevant factors. The number one issue is and will remain uneducated and willfully ignorant coaches that allow these things to continue. Focusing on the symptoms rather than the cause won’t solve anything.

If you want a training program that puts injury prevention first while still trying to get you the best results possible.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hp -

Great blog piece. I had already read Jonah’s piece and was surprised he didnt mention coaching and mecahnics. Reading about pitchers who have had pitching coaches mess with their mechanics only to get them injured in the minors and worse knowing a pitcher has dangerous mechanics but not changing anything for fear it will take away his effectiveness.

Tommy John Surgery - Blowout Cards Forums -

[…] about what causes pitcher injuries. Wasn't sure where else to put this so hope it's ok here Releasing Tommy John's Grip on Pitchers – Driveline Baseball __________________ Follow me on twitter @bigtrix36 I PC Da Bears, Seahawks, Mariners, Pirates […]

Frederick Manning -

Fyi: If Cressey and Matt Blake knew exactly what they were doing, some of their guys would have avoided shoulder surgery (Oliver Drake- Orioles) or avoided a flexor mass strain which can lead to TJS (Tim Collins – Royals). Just two examples of many going on there.

drivelinekyle -

Anecdotal reports of injuries are useless. It is impossible to reach 100% injury prevention levels for obvious reasons, and the fact that two out of hundreds (thousands?) of athletes at CP got hurt is irrelevant. A wider study would need to be done. Your comments are no longer welcome on this blog.

Chuck -

I can’t think of anybody more conservative with regards to training pitcher’s arms than Cressey. No overhead presses, bench pressing, O lifts etc. All pretty standard fair in any D1 college program. Elite athletic performance, whatever its modality, flirts with the possibilty of injury! I’m sure we’d all have pretty much the same objections and spew the same sophistry regaring etiology and culture if we shifted our focus to ballet dancing.

drivelinekyle -

I think Eric is conservative as well, but it’s important to note that the public face he puts on may be different than the one he uses privately. Given his client base, I can’t necessarily say it’s overly conservative.

Clint Lenard -

A guy lands on the DL for a forearm strain and he’s automagically labeled a TJS candidate? Wow, you must be some kind of wizard

Clint Lenard -

I woke up with a soreness in my TFL, should I just go ahead and sign up for a hip replacement?

Josh Heenan -

When we maximize sports performance via force production and speed we often increase some of our risks for injury. A 5 foot 7 guy chuckin’ mid to high 90s could have only so many throws to handle speeds that high.

If Eric didn’t maximize his athlete’s performance and help get them to the highest levels of their sport, this wouldn’t be a discussion of how conservative he is; it would be a discussion of don’t go to Eric because you won’t reach your potential.

B niswender -

If you have been working with athletes long enough you (we) know that athletes get hurt, playing at a high level is hard our job is to help them try to avoid injuries and if they do get injured help them recover faster and return better then when they got hurt. Keep up the great blogs/articles. I was the dbacks director strength and conditioning for 3 years back in 2001+ and this department is the scape goat for everything but in many cases we do it to “ourselves” because many strength coaches in baseball do a poor job of showing value in what we do. If you ever want to talk shop drop me a line I’m sure we would have lots to talk about [email protected]

drivelinekyle -

Thanks a lot Brian. Great comment. Hope to touch base soon.

Josh Heenan -

Spot on Kyle!

Chervey -

Great stuff Kyle. Totally agree that ignorance and stubbornness is the main factor here. We have more information available to us that is even more accessible than it used to be yet people think they know it all. Something I noticed as you were debunking all of the theories for increased injuries is that it sounds like these are people from an older generation and are basically cherry picking aspects of the baseball landscape that weren’t around when they were an amateur. With no real evidence presented, nautrally.

My question is if ignorant and uneducated coaches are the issues, have coaches become more ignorant and uneducated than they were in say the 70s, 80s and 90s? Or is it that these injuries are more easily detectable and are more public now because of increased media attention? 20 years ago did we even know what college pitchers were injured, let alone undergoing surgery?

Nobody Said It Would Be Easy | Kyle Boddy -

[…] get me started on Lean Theory zealots), education, and my industry of choice, sports. In my latest article

The Change: Odrisamer Despaigne | FanGraphs Fantasy Baseball -

[…] I think Jeff Zimmerman‘s research on breaking pitches and injury and Kyle Boddy’s position statement on the subject are better indicators of why we don’t see more pitchers throwing so many breaking […]

Brett Anderson’s Breaking Ball: Slurve’s Not a Dirty Word | FanGraphs Baseball -

[…] sometimes get short shrift these days. Perhaps because of their strong platoon splits and weak (but probably real) correlation with injury, it’s the change up that teams are insisting their pitchers learn. […]

2017 Greensboro Grasshoppers Season Preview | Fish On The Farm -

[…] quintessential expert of Tommy John, points out the carelessness of coaches at the entry levels in a quote to DriveLine Baseball by saying the […]