Individualization in Athletics: Potential Points of Failure

Individiualization.

It’s the solution to everything in coaching. Trainees want to be treated as individuals with specific needs and get personal attention to solve their issues, and coaches promise it to them in droves. Personalized workouts, custom-built templates, individualized programs, everything is based around the individual and tailored to their needs.

This isn’t a bad thing, by and large. Bad CrossFit boxes ignore this and program Workouts of the Day (WODs) blanket across their population and get people hurt doing high-rep Olympic weightlifting. Good ones understand a reasonable on-ramping procedure and the importance of mobility as drilled by famous CrossFitters like Dr. Kelly Starrett. Baseball is much the same – bad facilities, college programs, and pro teams treat their players like cattle, while good ones understand each individual responds differently not only physically, but emotionally and mentally as well.

Individualization is now “baked in” to most good programs, where a pre-determined template is configured around an athlete’s needs based on screenings or other key performance indicators. This is a great way to show individual attention to an athlete, gain efficiency, and scale the trainer’s business in a reasonable way. Doing from-scratch individual programs won’t scale for more than 20 athletes (at most) per trainer, and handing out copied templates to everyone won’t get the best results (and client retention will go to crap).

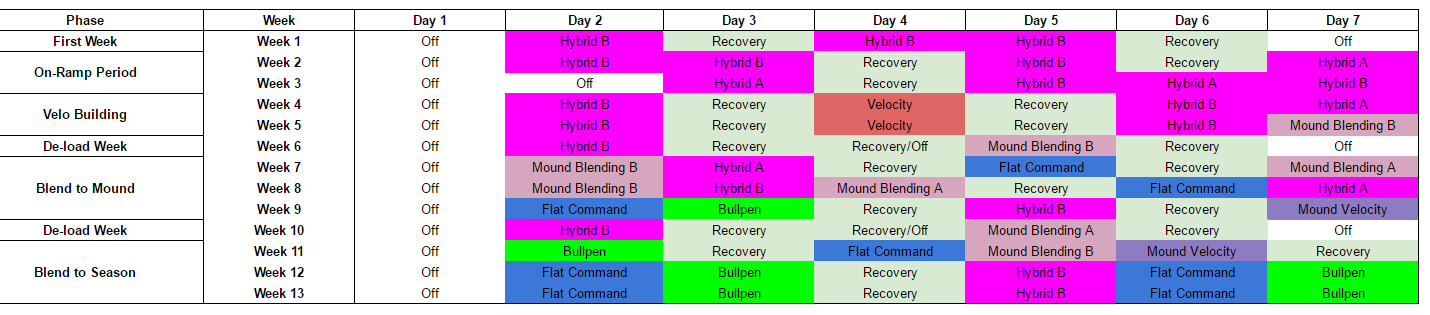

Our flagship training program, Hacking the Kinetic Chain, has tons of examples of this in the website’s back-end database:

Unfortunately, there are two cases where this type of “individualization” can fail, and it happens on both extremes of the continuum of athlete success.

But First, Training Phases

Legendary trainer Mark Rippetoe (Starting Strength, Practical Programming for Strength Training) described the training phases an athlete goes through, guided solely by the stimulus response the trainee is encountering. These labels are not good or bad, but merely talks about how programming must be modified – individualized, if you will – for the trainee depending on how he/she responds to stressors.

Here’s how I see the training phases:

- Novice: Trainee recovers quickly from training sessions and high volume can be piled on with regularity. A first-time lifter can squat three days per week, adding 5 pounds per training session for three sets of five without encountering overtraining symptoms. This window produces extremely fast and linear gains in strength, speed, and power. Programming is very simple, since anything more complex is both unnecessary and will likely reduce efficiency.

- Advanced Novice: Trainee recovers slightly slower but doesn’t yet need a fully periodized program. Adding deloading cycles or planned recovery days will be enough to restore function between hard training days. An athlete may only squat twice per week in this phase, dropping one heavy lifting day.

- Intermediate: Trainee has trouble recovering fast enough between training sessions (and is unwilling/unable to gain bodyweight to improve recovery, a topic for another blog post) and the programming needs to reflect a longer period of time – four weeks is the typical first training “block.” Specialization occurs in this phase; a power athlete will add more medicine ball exercises, a speed athlete will add more partial drills, a bodybuilder will add more hypertrophy training, and so forth.

- Elite Intermediate: Trainee needs a much longer look at training periodization and the coach should be getting a good sense for the athlete’s genetic asymptotic limits. This phase takes approximately 2+ years of hard, sustained training to reach, interrupted only very slightly by competition (for example, a college athlete who takes in-season competition seriously will likely never reach this point). If the athlete is 6’2″ 205 lbs with a solid diet, supplement plan, sleep patterns, and training history, but increased caloric intake – no matter how “clean” – causes disproportionate increases of body fat compared to muscle gain, the athlete is not likely to add muscle reasonably well going forward and is in this category. If the same athlete is stuck at a 3RM Front Squat of 390 pounds and any attempt to increase this to 400, regardless of programming, causes large regressions in other areas, the athlete finds himself in this phase. When in this phase, it’s important to come to grips with the fact that you are what you are going to be when it comes to basic, generally mutable traits – strength, power, speed, body composition, etc – and deploy your finite training economy wisely.

- Advanced: Trainee now thinks in terms of years, not months, when it comes to training goals. This phase is never hit from a general mutable sense for baseball players and is restricted to competition strength/power/speed athletes where the training reflects the competitive event (powerlifters, sprinters, Olympic weightlifters, etc) and highly complex skill is not a factor – this is not to say that sprinting is NOT complex, but pitching a baseball is orders of magnitude more skilled given the degrees of freedom involved.

If it wasn’t clear, it goes Novice -> Advanced Novice -> Intermediate -> Elite Intermediate -> Advanced in order of increasing complexity.

Where Individualization Fails: Novice Phase

Individualizing a novice’s workout is completely counter-productive. The Novice Phase period is where you can literally pile on a ton of basic work and they’ll get amazing stimulus from the simple stuff in addition to the fact that mastering the basic movements is a prerequisite for doing anything fancy down the line, and retraining movement patterns is way tougher than training them for the first time.

If a pitcher is 15 years old, sitting 68 MPH, and is weak with very limited throwing volume in the past, keep it very simple and very repeatable. Individualizing workouts here only serves to distract the client, usually with the intention of providing perceived added value so the trainer can keep booking sessions and padding his wallet. The athlete really doesn’t need a coach here. He needs self-motivation and consistent work in the weight room, dinner table, and football field long tossing.

Where Individualization Fails: Elite Athletes

This off-season we saw a very successful professional pitcher (not Brandon McCarthy above, though he’s a client) who had serious velocity loss. When he arrived for assessment and screening, we put him through our manual testing and our two-dimensional video-based kinematic automated screening. This athlete presented with a unique profile relative to our professional athlete metrics database:

- Previous lower extremity injury in the past, presently asymptomatic but led to reduced training time

- Extremely low ability to create shoulder internal rotation torque at relevant joint angles

- Very low trunk rotation range of motion

- Low rotational power in Keiser general movements

- Elite long jumping + lateral jumping distance and power

Frankly stated, none of our “individual” programs would be useful for this athlete, since our templates are largely geared towards attacking the Advanced Novice through Intermediate (and some Elite Intermediate) profiles which makes up the vast majority of our training population. This athlete does not have any glaring mechanical weaknesses when pitching, and even if he did, he was an older and very successful MLB pitcher who wouldn’t be able to tolerate movement retraining at this time.

While the general throwing drills outlined in Hacking the Kinetic Chain were used with our Plyo Ball ®, we had to make some specific adjustments to the program that fall outside of the usual scope of how we attack weaknesses. Low internal rotational torque values are not common in professional athletes; if they have a deficit, it usually presents itself in external rotation strength, which is a more sensitive measure of projecting future arm injury than simple range of motion testing (ex: GIRD testing). Most pitchers have the ability to internally rotate with power, since that is the nature of their job. In this case, limited throwing on-ramping was part of this, but the pitcher was already throwing in competitive situations. To attack this weakness, we prescribed manual isometric work at specific joint angles applying internal rotation torque against a fixed object and heavily-biased his throwing load with overload objects – 450g and 225g Plyo Ball ® and 6-11 oz. leather weighted baseballs in catch play. We also stayed away from maximum effort throwing such as pulldown / running throw work, since it wasn’t a specific way to attack the issue at hand.

Our High-Performance trainers that worked with the pitcher used manual therapy techniques (FAKTR, PRI, specific trigger work) to help restore trunk rotation range of motion, which was very effective. We then blended that with throwing drills to ensure the gain in ROM would express itself dynamically on the mound, and used high-speed video to check this metric.

However, while velocity was ticking up significantly in just two days of assessment and work, trunk rotation wasn’t being maximized. This is where years of experience with professional pitchers and having a wide base of knowledge can be very useful in practice despite the situation never specifically coming up in the past.

I was working on integrating all of the modalities together, and since rotation was still not being expressed dynamically, I decided to use the a style of training that I thought could maximize transfer: a type of French Contrast training. Named after French sports scientist Gilles Cometti, this is a method of training that seeks to maximize rate of force development and power. While these benefits are useful, they were not the main reason I chose to use a contrast method of training; contrast training is also a very good way to layer general movements to skilled movements to improve the transfer of training in a shorter period of time.

We had this pitcher do the following contrast cycles:

- Keiser rotational chop, 2 sets of 3 both directions, measured power output

- Plyo Ball ® Rocker throw, 2 sets of 5 with 450g and 225g Plyo Ball ®, measured velocities

- 7 pitches off the mound, measured velocity and took 300 frames per second side high-speed video with our Edgertronic cameras

After five cycles of this while tweaking the reps/sets scheme as the pitcher tired, he posted a +8 MPH gain (still not his working velocity, but a big increase!) in just a single day of working. The athlete didn’t get any stronger or faster in a few days of training, but professional athletes competing at the highest level almost always have the potential inside of them – it just requires figuring out how to attack the movement patterns, restrictions, or other issues preventing it from being expressed.

The pitcher left with a four-week program to continue improving strength/power metrics, throwing-specific metrics, and proprioception work to do on his own, truly individualized for an elite athlete. Coaches who work with elite talent should be well-read and must keep up with new training ideas in case they need that Swiss army knife in the back pocket – just know that you should only be using the tools very sporadically. If you find yourself using new ideas on a regular basis, your templating base of training needs to be better tested, re-tested, and documented.

(This article was written by Kyle Boddy, Founder and Director of R&D of Driveline Baseball)

Comment section