The “Big Lifts”, Common Mistakes, and How to Fix Them – Part II – The Bench Press

In part one of this series we discussed the some of the common technical culprits that are generally seen in the squat – an exercise that is one of the most prevalent and effective exercises in all of performance training.

Today we will discuss another major exercise that not only has at least some variation of it used in nearly every strength and conditioning program, but that also is a staple exercise for the Driveline-U program: the Bench Press.

Some semantics to first get out of the way: when I use the term Bench Press, let’s understand that I am applying the term generally for all bench pressing variations – just as “squat” can be a general term for the squatting movement as a whole – unless otherwise denoted (e.g. if I say “Dumbbell Bench Press”, or “Barbell Bench Press”)

The purpose of this discussion is not to debate the merits of the bench press for baseball pitchers. Rather, since the bench press is generally used in nearly every program in some fashion or another (from baseball to football, bodybuilding to powerlifting, and from training age 0 to 20), we will instead discuss some of the technical faults seen in novice lifters when performing the Bench Press, and then pose some solutions to correct them as simply as possible.

Let’s begin with the set up.

Lack of Lower-Body Tension

The Bench Press is obviously an upper-body dominant movement; personally I categorize it as an upper-body press/push (more on this later). But, that does not mean it has no lower-body involvement whatsoever.

In fact, a strong bench press actually incorporates a good amount of the lower-half to generate tension and stability. Very few novice athletes understand this though, as I have seen through countless sets in the high school weight room and via video in the Driveline-U program. This isn’t necessarily the fault of the athlete, as very few amateur-level coaches will teach much to do with the lower-half during the bench press (that is, unless they are weightlifting coaches teaching foot placement and lower-back arch).

Regardless of the reasoning, the athlete should learn to utilize the lower-half during the bench press for optimal efficiency and strength.

So, what needs to happen in order to create tension in the lower-half during the bench press? For starters, here is what we don’t want to see: wobbly legs, an unsteady torso, and “happy” or “jumpy” feet. Instead, we want to see firmly planted, activated hips, and a rigid torso.

Here’s the analogy I like to give: imagine a wooden dining table. First picture it with wobbly legs that aren’t screwed in. Could we eat dinner on the table? Sure, but could we stand on the table to, say, change the light bulb in the light hanging overhead? Probably not without it collapsing underneath us.

Now picture the same table with the legs screwed in tightly. Not only would it serve as a sturdy dinner table, but it could also hold a lot more weight.

It is a crude example, but hopefully it gets the point across that tension in the lower-half can create stability for the rest of the body.

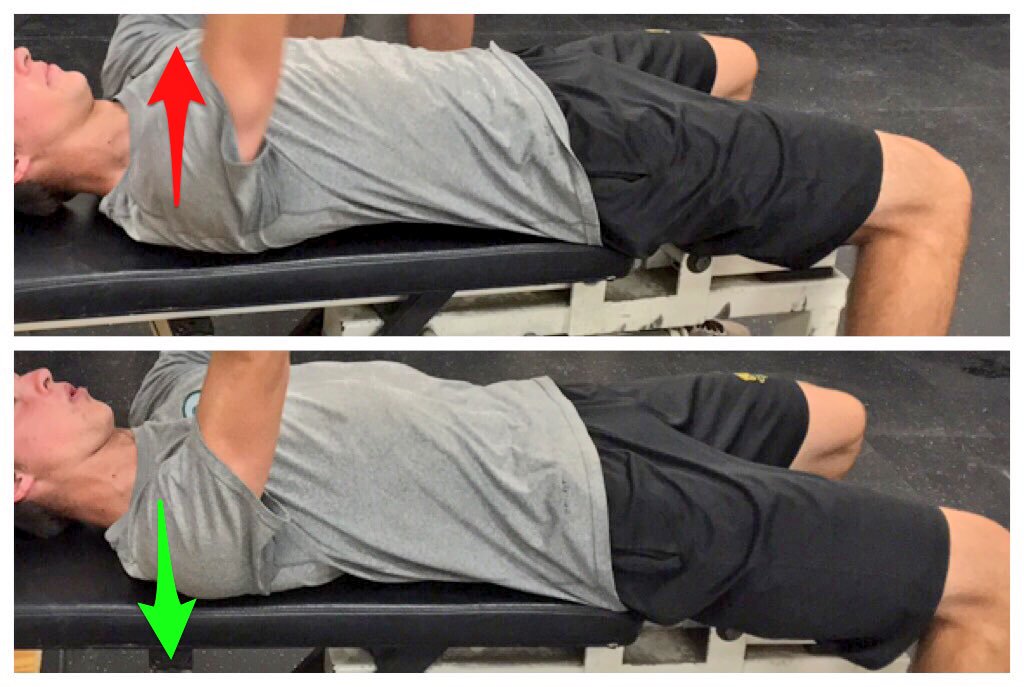

To create tension in the lower-body during the bench press, I generally make the following suggestions:

- Lay back on the bench and then plant each foot firmly on the floor in a very wide stance

- “Screw the feet into the floor” and spread the knees; squeeze the glute muscles to help facilitate this. You will immediately feel tension in the hips

- Keep the feet planted firmly throughout the lift

Also, I may use the following exercise to help the athlete find the appropriate stance, foot placement, and glute activation:

Now let’s talk about a common upper-body fault.

Too Much Scapular Movement at the End of Each Rep

Above I discussed how I personally categorize the Bench Press as an upper-body press/push movement, and many of you rolled your eyes and said, “Well, duh!”

But, the reason for noting this categorization is because I am actually separating the bench press from other movements that, on the surface, appear to be a press or push – such as the push-up or landmine press.

These movements, rather, are what can be known as “Upper-Body Reaches” whereby the difference lies in the movement (or lack thereof) of the scapulae during the repetition.

During upper-body pressing exercises, such as the Bench Press, the scapula must remain locked down in retraction on the bench for the entire duration of the rep and set, for both safety and efficiency. That is because the Bench Press is a closed-kinetic chain movement where nearly all of the movement is coming through the arm. Retracting the scapulae during the Barbell Bench Press, Floor Press, and Dumbbell Press not only provides a stable base through which to press the weight, but it also decreases the distance that the bar must travel during the rep (less distance at the top) thus necessitating less overall work each rep.

Push-ups, landmine presses, and cable presses, on the other hand, are defined as upper-body reaches due to their open kinetic chain nature and freedom of the scapulae to move. In fact, these movements must incorporate proper glenohumeral rhythm and timing in order to be most safe.

Yet, it is in the inclusion of the Bench Press with novice trainees that we often see so much scapular protraction (or reaching) at the end of each repetition. They reach for the ceiling, rather than push though the base (i.e. the retracted scapula).

Will one repetition of reaching under a heavy load necessarily hurt the throwing shoulder? Maybe not. But, will varying volumes and intensities culminate in the insidious onset of discomfort or pathology over time? More than likely.

The idea, then is to educate the athlete on scapular positioning prior to ever pressing the barbell or dumbbell for the first time. In fact, I personally include it as a part of the set-up procedure. If we are going to teach the athlete to create a stable base with the lower-half (as discussed above) then we ought to teach them to create an equally stable base in the upper extremities.

This takes some visual demonstrating, verbal cues, and lightly loaded experience. But, with time and diligence, scapular retraction during the Bench Press can not only be learned, but it can be appreciated as a mechanism to create a stronger and more effective Bench Press as well.

***

While the Bench Press may make up varying factions of any one coach’s program, it is critical that when it is utilized, that it is done so in the safest and most effective manner – much like any other exercise.

The aim of this discussion was to discuss two major technical flaws with the Bench Press when implemented by novice trainees, and to provide a means to help correct them. In part three of this series we will discuss the Deadlift.

You can find the next two installments of the series below

Part III: The Deadlift

Part IV: Pulling Exercises

Comment section