Player Development: Integration and Communication for Better Results

Player development is the holy grail of baseball. Velocity, movement, command, injury prevention: the teams that can develop these traits better and faster than others are the ones that will be, theoretically, hoisting the Commissioner’s Trophy more often than any others. This doesn’t just play at the major-league level either. In fact, it’s almost more important at the college and high school levels where you can’t just shovel out huge salaries or make a trade to get the pieces you need. At the high school level, you can’t even recruit; you get whoever lands in your school district. This is why player development is so crucial to the success of an organization or team. This is why teams should invest big sums to further their players’ development.

However, that’s not what’s happening for the majority of baseball teams, especially at the affiliated level. This is a problem, because players have particular expectations. Like many others, I believed that if I was good enough to make it to the next level, to play college ball, to just get on an affiliate roster, there would be a coach there who would help me become a better baseball pitcher—because I knew I had more in the tank. Does this sound familiar?

The higher level you get to, the better coaching you believe you must receive. But that’s unfortunately not always the case, which brings us to this quote from a current minor leaguer:

“There is no player development. Teams aren’t adding velocity or any of that, the teams that appear the best at player development are the teams that are the best at not screwing their talent up.”

So, is that what good player development is? Is it just, not getting in the way? Or should it be something more?

First, we need to acknowledge that player development in-season is very difficult. While improvements can be made, development isn’t a primary focus when trying to compete and win baseball games.

Second, it comes down to the offseason—when high school and college players may be playing other sports or working around rules of contact hours, and minor leaguers are looking for another job to make ends meet.

Finally, you get into what players are doing in the off-season. You wonder if everyone is on the same page, especially when when almost thirty percent of all injuries needing surgery occur during spring training (Lindbergh, 2015).

So, if the current model isn’t ideally servicing our athletes, how do we change it? Now, I am by no means privy to all the details of player development in affiliated baseball nor am I aware of what every college and high school is doing around the country. I also realize that every player has their own unique situation and circumstances. However, since I have spent time around major and minor league clubs and coached college baseball for five years, I want to share what I see as some of the biggest issues currently facing true player development.

Communication

Any sort of self-help or leadership book almost always talks about communication. Communication as a whole is incredibly important—just ask your significant other; relationships don’t work without communication. However, often and at almost every level, we see a dearth of communication among the skill coaches, strength coaches, and the ATCs. (We won’t even begin to bring the R&D folks into this to keep it simple.) While this is not always the case, more often than not each group is siloed into their own realms and relegated to certain tasks: get them healthy, get them strong, make them throw strikes, etc. These shouldn’t be individual tasks; each group can have a positive impact in a cohesive manner.

This is where, when you really get rolling, true player development begins.

For example, consider a pitcher who’s struggling to throw strikes. The pitching coach works with him, maybe tries some mechanical changes, some drills, but however he chooses to correct it, the player either gets better or he doesn’t. The important part here is that the athlete’s skill development often begins and ends with only the pitching coach. Now, imagine instead the pitching coach takes a look at the struggling pitcher, realizes he has some mechanical inefficiencies with his lead leg, sees there’s a lot of lateral shifting, and knows that it doesn’t seem to brace well. The pitching coach then programs certain drills to improve lead-leg brace and then informs the strength coach and ATC about it as well.

The ATC does an assessment, learns the athlete is lacking internal hip rotation, so no matter how much the pitching coach does, he would have never helped that athlete to block his lead leg and improve his command. However, knowing this, now the ATC begins working to manually increase hip IR, and the strength coach programs mobility and strength work to help strengthen the hip through its newly opened range of motion. The skill coach can continue to help the athlete pattern that movement, while being cognizant of the athlete’s limitations and how he’s progressing his development.

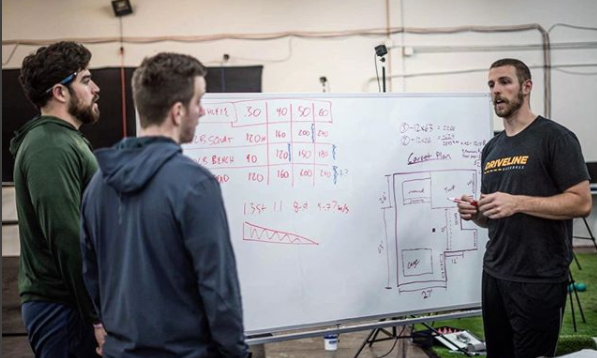

The idea behind this process started when Kyle Boddy and Jack Scheideman took a trip to Altis, where they watched Stuart McMillin, Dan Pfaff, and others provide manual therapy while observing their sprinters’ warm-ups. They used manual therapy to adjust and correct for any movement restrictions they noticed in their athletes. The athletes, knowing their bodies and their “feel” better than anyone else also provided feedback so that the trainers could correctly treat and fine tune the athletes for that day’s workout. Through this simple communication loop, they began to not only bridge the athletes’ development gaps, but also improve their performance, allowing them to be more prepared for that day’s training or competition.

I should also point out that we know this scenario isn’t available for everyone, but it’s important for school coaches to reach out to their ATC and for facility owners to start networking local PTs, ATC, and chiropractors to refer athletes to. The goal is not to have athletes become dependent on treatment, but to provide a means of identifying limitations, treating them, and then putting athletes on a sustainable path that will allow them to be self sufficient through warm-ups and training.

My question then, is, Why are we not doing this with at least bullpen pitchers in baseball? If sabermetrics is telling us that the highest-leverage innings come later in the game, why do we not want these athletes as finely tuned for performance as possible? They often warm up for four hours before the start of the game. Four hours!

Now, that’s not four hours before they pitch; that’s four hours before first pitch. So, tack on another one and a half to two or more hours from there, and you can’t tell me that after getting hot six hours ago things haven’t stiffened back up. Just think about how you feel after sitting behind a desk for a few hours—great right? I doubt it.

So why would you not have a manual therapist working on helping pitchers feel better and become more finely tuned an inning or two ahead of their potential appearances?

Terminology

While this falls under communication, making an effort to learn terminology and gain knowledge in departments outside of your own not only helps make you a better coach or trainer, but also facilitates ease of communication among groups. For example, if you understand the strength and conditioning concepts of energy systems and training economy, as a pitching coach it can help you better structure practices and coordinate with the strength coach on lifting, recovery, overreaching, and other important training factors required for player development. The same goes for the strength coach, who likely has a good understanding of the movements required for success in the sport but can benefit from understanding the movement and mechanical principles the skill coach is looking to have his athletes perform.

There are other examples of how important it is to know your training staff’s philosophies, what they’re doing to train athletes, and the terminology they use when speaking to athletes in order to make you and your athletes better, so we won’t wear this out. Just remember, the more you know about every aspect of your athletes’ training, the better you will communicate and the better you will be at training them yourself.

Knowledge

This is something I’ve been guilty of and that I’ve seen many smart coaches struggle with as well: it’s ok to share knowledge. It’s ok to let people into your world and to tear down that silo. All too often we feel the need to protect our knowledge. We live and work in a competitive industry and sometimes knowing more than everyone else seems like job security. You’re valued more if you know more, right? As wrong as this is, I’m sure we’ve all worked with others who have had this kind of attitude. Some of them even try to brow beat you over the head with their knowledge.

One major league strength coach I spoke with said he worked with a pitching coach early in his career who used his knowledge of biomechanics to throw other members of his staff under the bus when things went south for his pitchers. That kind of thought process doesn’t contribute to athletic development and success no matter how much you know. Not sharing information and not learning more of what your coworkers’ departments are doing limits you and your team’s ability to impact athletes positively. It also sets up a poisonous work environment. Regardless of how much that coach knew about biomechanics, you can’t tell me he was going to have long-term success. It’s just not possible with that mindset.

Technology and Feel

This is the last piece of player development we’ll touch on, so let’s set the record straight right away: Feel is not real, and technology is not the answer. You can hate sabermetrics; you can hate Rapsodo and edgertronic cameras. You can believe launch angles are the devil and deny batted-ball exit velocity.

However, the truth is you need these if you want to give your athletes the best opportunities to develop, but remember that these tools are not the answers in and of themselves. They’re simply a means of measuring improvement and providing feedback for quality control. You won’t believe how many athletes think they’re throwing a curveball only to discover on the Rapsodo that they’re actually throwing a 30% spin efficiency crappy cutter. While it may even look moderately ok to the eye, for some reason it keeps getting tattooed for doubles in the gap. Like it or not, the technology is there to help understand the why of what is happening.

But as I said, technology alone is not the answer, it needs a good coach to be able to interpret the data and communicate it to his athletes. You can’t just use the Rapsodo and edgertronic cameras to develop a new pitch if you don’t understand seam orientation, spin axis, spin rate, etc. A good coach provides feedback and suggestions based on an athlete’s feedback (i.e. feel) and data from the technology, and the same goes with hitting and using a Rapsodo or anything else you do. Regardless of the task or environment, there’s a necessity of having a coach there to discuss feel and direction; we just want to use whatever technology it is to help aid that process. It’s not meant to take over the process and it certainly isn’t there to replace a coaching staff. Instead, it should empower them to better own their athletes’ development.

Don’t be afraid of data and technology—baseball is going to the nerds and for good reason. They’re finding ways to analyze the game like never before, and this means more opportunities to understand the game and make your players better. Don’t run from it; embrace it, because players will always need coaches to show them the way and if you’re willing to look, the way forward is starting to have much better signs to guide us.

The Wrap

In closing, I just want to reiterate that for organizations and teams to experience peak player development, there needs to be communication. You can buy all of the technology you want, you can throw weighted balls, you can have the best, most educated coaching staff in the country, but if you’re not fully integrated with every department, if you don’t utilize your strength coaches, skill coaches, and ATCs to best of their abilities, you’re missing huge opportunities to develop your athletes.

We need everyone discussing what they’re seeing and sitting down together to formulate development plans with their athletes. It doesn’t matter if an athlete struggles with exit velocity, command, health, etc, everyone can have an impact on improving each athlete’s development. This is one of the reasons we’ve been so successful at Driveline. The more we’ve integrated all aspects of our floor into one, the better results we’ve seen, and the lower our injury rates have been.

So, let’s breakdown the silos. It’s time for a better age of player development where we don’t just avoid screwing talent up, we take talent and make it great.

This article was written by Director of High Performance Sam Briend

Ben Lindbergh. March Sadness: Understanding the True Cost of the Spring Training Tommy John Surge. https://grantland.com/the-triangle/mlb-preview-tommy-john-spring-training-surge-zack-wheeler-yu-darvish/ 2015.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don Oliver -

I believe that your Research department should implement another aspect of assessment in pitching recovery in the form of MuscleSound. It will help to assist your team in analyzing how muscles recover after throwing and how much fuel or energy the muscles need to achieve optimal muscle size and composition. Which to me means once the athlete is assessed with the Muscle Sound protocol then that athlete has a baseline fuel level. Then keep track of his fuel level( protein, water levels, nutrition) every 2-3 days and monitor his velo with his muscle recovery and fuel levels. The program is simple to use. Plus at driveline you have a steady sample size of pitchers A university would have the same sample size. Meaning more pitchers or throwers to assess and be able to monitor and get to optimal performance. My hunch is this: if a pitcher is dominating at every start and throwing 95-98 or even. 88-93… but only lasts 4-5 starts then hits a dead period. Could it be that the Muscle Fuel levels are low and we do not even know? Meaning If we track muscle fuel levels and compare with actual performance is there a correlation. Could this information help each athlete ? Help each pitcher get better? Help an underdeveloped pitcher get better? I think so. After all what could it hurt? I have a Muscle Sound but really do not have access to constant athletes. Use it more for post op patients and work related injuries. But this seems to be the missing link in recovery and management of velo for pitchers after or during throwing. I have no finanacial interest in Muacle Sound but they are based in Denver Colorado and way to reach. From there I feel like Droveline can set up a protocol very easily with some outstanding conclusions that could change the way PTs., ATC and MD and pitching organizations look at development. Why not be the pioneer ? Also could be done with hitters and any throwing athletes . The people who implement the MuscleSound can all be trained. The software for each assessment is easy to read and is cloud based.

Don Oliver -

Integrating MuscleSound imaging of all athletes (pitchers and hitters) on a regular basis will provide an area of research for Driveline that is missing. The correlation of muscle health ( fuel and composition) with velocity gains. I have a Muscle Sound imaging decision cue that I use on my patients and a small amount of athletes ( my son is a high school pitcher). So what I want to know is how is fuel levels correlate with his velo and what will his velo be when his fuel levels ( energy ) is full. I have been doing this for 3 weeks and his current fuel stays is low A compared to national norms and to his contrlateral side. So if he is at 29% fuel capacity now and throwing 87-91 as a 17 year old what will he be throwing at full capacity. How long do W.A. or take him to replenish his muscle fuel after he pitches a complete game. These are all viable questions that can help everyone. I would like to see Driveline start to include this data with their research. It is easy to implement and the learning curve is easy. The tech savvy people who can scan the muscles are needed but a trainer or PT can easily do this. Muscle Sound is in Denver Colorado and easily accessed online for information.

Kyle Boddy -

We are open to the idea, but it is cost-prohibitive and the device lacks the open source support we require for our workload tracking integration. If the cost came down and the device/data was opened more, we would strongly consider it.

Rafael -

Great article