The Impact of the Autonomic Nervous System on Baseball Players

At some point in their careers, many baseball players have to spend time under the care of a medical provider.

What we tell athletes under that care can have long term psychological effects that present themselves in physical manifestations.

Traditionally, the standard of care has been to identify areas on the body that are not moving optimally, assign blame to those areas as the reason an athlete got hurt, and then “fix” those areas.

In a short-sighted way, this makes perfect sense, and this model has helped many athletes.

However, the psychological impact this can have on a person is often ignored—and it is an impact that is often more severe for an athlete trying to allow their body to perform at peak levels.

PAIN ISN’T JUST ABOUT INJURY

I recently worked with an athlete who had been to physical therapy on and off for the last several years with multiple lumbar stress fractures. He was always diligent about completing his home exercise program and listened to his doctor’s instructions.

For much of his high school life, this athlete was told that he kept getting injured because of weakness in his core and hips, along with having poor thoracic flexibility. His fracture has now been healed for some time, yet he is still having pain with baseball activities.

During his exam, he demonstrated good mobility with some remaining weaknesses. When he discussed what he is doing at home, he explained the exercises doctors gave him in the past.

I asked him how often he is thinking about protecting his spine. He replied, “Pretty much all the time”.

At that point, I talked to him about how his fracture had healed and explained that any future core strengthening should come from his strength program.

We began weaning him off the exercises that were part of his normal “spine care” routine, and after a few visits his strength was back to normal and his pain was significantly reduced.

Injuries are much more complex than “this body part is inefficient, therefore this other area suffers”.

Recent workload, fitness level, nutrition, amount of sleep, mental stress, environmental changes, and many, many other factors can all play a huge role in the breakdown of tissue.

Those factors aside, what can often get overlooked is the very real part that mental and emotional stress can play in an athlete’s well-being.

THE IMPACT OF STRESS ON THE ATHLETE

Stress is how your body responds to events in your life.

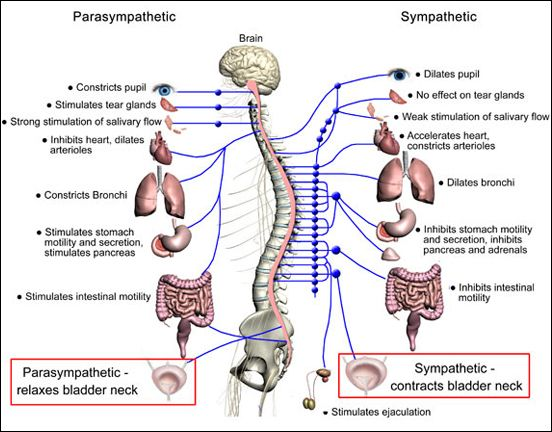

Relationships, school, work, and training are all examples of stressors. Your experiences and how you handle these stressors can move your body into a sympathetic (fight or flight) or parasympathetic (relax and recover) state.

Ideally, your body maintains a nice flow and balance between these two states.

When the time comes to train and perform, you want your sympathetic nervous system to be more active. When training or a game is finished, it’s time to move into a more parasympathetic state for recovery.

Spending too much time on one end of the spectrum can impact performance and health in a negative manner. They can make activities more taxing on the body than normal, especially if one becomes more sympathetically dominant.

An example of this would be an athlete being sorer from a 40-pitch bullpen during a week where they had three exams as opposed to a week where they had no tests.

The stress of the bullpen didn’t change, but they’re more likely in a sympathetic state due to the stress of the exams.

As previously stated, certain stressors can move your body into a more sympathetic or parasympathetic state.

Let’s take another example of a pitcher I saw recently with a shoulder injury he sustained during the season. Initially, he had some tightness in the back of his shoulder that he was ignoring.

He continued to pitch through it, increasing tightness and fatigue and eventually sustained an injury. His shoulder has since healed and he has returned to his normal throwing routine.

But now he is nervous about feeling any tightness in the back of his shoulder. His body is more alert to that sensation than it was previously.

The tightness itself, which can be a normal consequence of throwing, is now a stressor that can move him towards a more sympathetic state.

This could be both a benefit and a detriment to the athlete. It can potentially alert him to fatigue and that he may need to cut back his throwing routine.

Or, he could take any tightness as a sign of potential injury, immediately shut down, and be unable to make any significant progress with training due to constant fear of re-injury.

An athlete’s experiences with medical providers can also lead to long-term stressors which can become detrimental. During recovery, he went to the doctor who diagnosed him with GIRD (a loss of shoulder internal rotation) as a major contributor to his injury.

He went to physical therapy, where they told him his injury was a result of weakness in his scapular muscles and tightness in his hips. Using our current example, just from this one injury experience the athlete now has the following negative thoughts associated with throwing:

- “Tightness in the shoulder means I’m about to get hurt.”

- “I have GIRD and if my shoulder isn’t flexible then I will get hurt.”

- “My weak shoulder predisposes me to injury.”

- “If I don’t keep my hips mobile, then I will get hurt.”

None of these statements are definitively true, however.

There are plenty of athletes with inflexible hips and shoulders who feel tightness during throwing but can still pitch at an extremely high level without ever suffering an injury. Does it mean this athlete doesn’t need to focus on those areas with his training ever? Of course not.

But he also doesn’t need to spend a half-hour every day focusing on corrective exercise for these areas. High-level athletic performance requires an athlete to have a great deal of trust in their body.

With every flaw an athlete possesses pointed out to them on a treatment table, it not only reduces the trust they have in themselves but it can also create a chronic stressor. This may drive them further towards the sympathetic end of the spectrum, reducing their capacity to adapt to other stressors that are already present in baseball and life.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

So, what can we do to ensure that athletes are still receiving high-quality care while not developing a fragility mindset?

Unfortunately, I don’t believe there is an easy answer to this question.

I do believe the answer starts with understanding that a great many factors go into an injury or decreased performance. While movement deficiencies do play a role, they likely don’t contribute more than workload, throwing fitness, recovery and so on.

Many times I have suggested the idea of taking “inventory” of what is going on in their lives. This can be an end of training reflection, journaling exercise, or some other practice. This can help identify any additional things in their lives that could be impacting their training.

Over the past week, maybe their arm has not been feeling great. But as they look back, they realize they are having trouble with a close friend. Or maybe they haven’t made any velocity gains, but they also haven’t been sleeping well because they are keeping themselves up at night worrying about it.

Giving themselves an awareness of stressors can have a benefit in keeping an athlete from being too sympathetically dominant.

Athletes, coaches, parents and health care providers should be educated about this process. They should also be educated on how adaptable the human body truly is. Even in the absence of “optimal movement”, our bodies adjust to stresses placed on it and become more resilient overall.

Focusing on building that resilience should be just as—if not more—important than trying to fix areas that are inefficient. Giving athletes that knowledge and the feeling of being a strong, adaptable human can become a huge asset for them in their goal of being a healthy, high-level athlete.

By Terry Phillips, DPT

English, Nick. “Sympathetic Vs Parasympathetic: Why Every Athlete Needs to Understand the Difference.” BarBend, 16 May 2019, barbend.com/sympathetic-vs-parasympathetic-athletes-benefits/.

Gill, Diane L. Psychological Dynamics of Sport and Exercise. Human Kinetics, 2017.

Kajaia, T., et al. “The effects of non-functional overreaching and overtraining on autonomic nervous system function in highly trained Georgian athletes.” Georgian Medical 3.246 (2017): 97-102.

Kennedy, Kyle. “Complete Autonomic Nervous System Management for Any Coach.” SimpliFaster, 11 July 2019, simplifaster.com/articles/autonomic-nervous-system/.

McEwen, Bruce. “Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators: Central Role of the Brain.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 8, no. 4, 2006, pp. 367–381., www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181832/.

Ritter, Mike. “Winning The Olimbic Games: Why You Need to Understand Allostatic Balance.” The Paleo Diet – Robb Wolf on Paleolithic Nutrition, Intermittent Fasting, and Fitness, 13 Feb. 2017, robbwolf.com/2015/01/21/winning-the-olimbic-games-why-you-need-to-understand-allostatic-balance/.

Comment section