Youth Sports Specialization and Youth Baseball

Every year, there are many discussions on what makes a player good enough to be a top pick in the draft, a top prospect, or simply a top player at the MLB level. Inevitably, these discussions cover a wide range of opinions that typically return to looking at how a key point in their development was during youth athletics. While top picks, prospects, and players will surely take unique routes to becoming the talented players they are, discussions connecting youth baseball players to future baseball success focus on one big problem and one must do: today’s players are too specialized, and the solution is to be a multi-sport athlete.

There are myriad reasons why parents and coaches insist that playing multiple sports is good for youth athletes. But moving from the idea that kids should play multiple sports to the actual practice of participating in multiple sports becomes difficult—especially when a youth athlete has aspirations to play at the highest level.

Today, we look closer at the cross-over skills from other sports to baseball while touching on some long-term athlete development (LTAD) topics. Playing multiple sports or practicing a wide variety of tasks may or may not help prospective baseball players.

Multi-Sport Athletes: Revisiting Correlation ≠ Causation

When discussing multiple sports and baseball, these are the two implied benefits of why playing multiple sports is good:

- Avoiding overuse of particular movements.

- Increasing overall athleticism, which helps performance in one sport. (Baseball in this case.)

Both of these can be true at the youth level (defined as younger than high school/eighth grade), but like most things, the relationship between multi-sport participation and single-sport success is more complicated. It’s very difficult to be precise on what helps develop skills that will maintain or grow as a player ages, especially at the youth level, which is part of the reason why performing a wider range of activities as a younger athlete is beneficial.

A point that we’ve made in previous posts is that the best baseball players are the best because they’ve played multiple sports can confuse correlation with causation: Better athletes are more likely to be asked or simply participate in multiple sports.

This doesn’t make playing multiple sports a bad thing. Participating in diverse sports is absolutely relevant for athletes, especially when they are not yet in high school. It is just not a guarantee that they’ll be better at baseball and that’s ok. Youth athletes need not only time to play sports other than baseball but also quality baseball instruction to succeed.

One obvious way to play too much of one sport is to eliminate participation in other sports. Risks are especially apparent to a youth baseball athlete’s arm and back because of excessive throwing and rotating.

Playing multiple sports helps build a foundation of varied movement skills. If we created a pyramid of skills, youth players will spend most of their time practicing fundamentals—not only the foundational skills of that specific sport but also fundamental movement skills.

So when we talk about whether playing multiple sports will help you get better at one, the answer is yes, to a degree. There should be some transfer of the foundational skills but not so much with the specialized skills.

Playing multiple sports can give athletes a break from one sport, and those other sports will give them a variety of challenges to help improve body awareness. In a youth baseball player’s case, playing multiple sports helps work on foundational skills and time away from throwing and rotating. This should help them improve across the board. Because at younger ages, the skills needed to work on are far more fundamental and movement focused instead of having a specific focus.

Think of the time spent coaching kids in football, soccer, basketball, baseball, etc. and simply how kids learn to be prepared and in an athletic position.

Youth athletes also have to practice specific skills of their own sport, but improvements in youth athletes are ripe for the picking when coordination and body awareness improve. This is where you can see the argument that playing multiple sports should help young athletes across the board.

Participating in multiple sports can also help them in the long run, beyond trying to play sports competitively. As mentioned in Long Term Athletic Development (LTAD) texts, players are more likely to participate in sports as an adult if they played them as a child. Which is a worthy goal to keep in mind if we want athletes of all ages to be fit into adulthood.

Youth sports should focus on fundamentals since they make up the base of the skill pyramid of an athlete. While much can be and has been written on fundamental movements, these are general sports skills that would often have overlap in the weight room: Can youth athletes, squat, hinge, jump, shuffle step, get in an athletic position, push, pull, and develop the necessary awareness or perception of their surroundings to be successful in various sports, not just baseball?

But as a youth athlete starts to age and works his/her way up the skill pyramid, stark differences appear between sports. These differences in physical skills also come with differences in awareness or perception that makes them stand out from those in other sports even more.

Limits of Cross Training: The Role of Perception Action Coupling

Academic texts and other descriptions of perception action coupling can be dense, but we can sum up its importance like this: Actions taken is sports are not executed in isolation. Athletes constantly take in information (audio, visual, kinesthetic) to make decisions. This information is constantly processed in the planning and execution of movements in sports.

More simply, if you try to cross a street, you don’t just walk up to it and cross. You don’t know when or how fast you should cross the road (action) until you observe how quickly oncoming traffic is approaching (perception).

Put this way, it shouldn’t be surprising that sports require athletes to make a series of decisions based on any given scenario. Perception action coupling is simply specifically directed at how these relationships affect motor learning and sports performance.

Laying that out more specifically should make us realize that the required actions to be successful in baseball are unique when compared to other sports.

Broadly speaking, there can be more parallels drawn between the perception action relationship in football, soccer, basketball, rugby, and other sports than between any of those and baseball. While the task goals are slightly different, the perceptual challenges players are exposed to in football, basketball, rugby are quite similar to one another relative to baseball. So, the carryover between playing those sports and baseball are limited beyond the foundational movements described earlier.

While both football and basketball players attempt to “get by” their defender in open space (albeit with difference constraints), baseball players don’t have that interaction.

Which is why as players age, more sport-specific practice is becomes increasingly relevant rather than focusing on a wide range of fundamental skills. This doesn’t mean fundamental skills become less important, but as they age, those skills should be more ingrained and can be worked on in the weight room. This means they should take slightly less time to maintain those skills and spend more time improving sport-specific skills.

This has repercussions related to adolescent sports and wanting to play baseball at a high level. The problem is that it’s difficult to give broad guidelines on how to throw and learn to rotate fast enough without doing it too much—while also playing other sports.

This is also related to why professional teams like multi-sport athletes: without focusing all their time on the skills of one sport, they’re good enough to get drafted. Teams aren’t looking at a three-sport high school athlete and saying, “Well he can read defenses as a QB, and dunk a basketball so that means he has the ability to develop a great changeup.”

They look at multiple-sport athletes and see how good they are, looking for opportunities for improvement once they start dedicating all their time to the specific skills that baseball requires. On the flip side of what we mentioned earlier, as youth athletes get into high school the ones who are bad at throwing and rotating may need more time, or more specific practice, to improve those skills.

This adds nuance to the question of whether to specialize or play multiple sports. Because a lot of it depends on what an athlete’s goals are and how good he is.

Which is why things get more complicated as athletes age; skills need to become more specific, and baseball itself is unique, which is where differences in perception and action between sports comes into play.

Walking the Line Between Just Enough and Too Much

When a youth athlete, or a parent of one, is dedicated to playing at the highest level, it’s understandable why they often default to a “more is better” mentality and often cross into the field of early specialization in hopes of achieving long-term success.

While much has been made about the 10,000 rule, more investigations into its relevance in recent years has shown learning a skill to be more complicated that simply hitting 10,000 hours. Not every athlete starts from the same baseline of skill, the quality of practice is especially important, and whether we want to admit it or not everyone can become an expert. Getting especially relevant and good practice is key to developing but it’s more complicated than just working towards a set number of hours.

After all, the more you practice a skill, the better you should get at it. For instance, in 2019 28.5% of MLB players coming from countries outside the US and many practically specialize in baseball from birth.

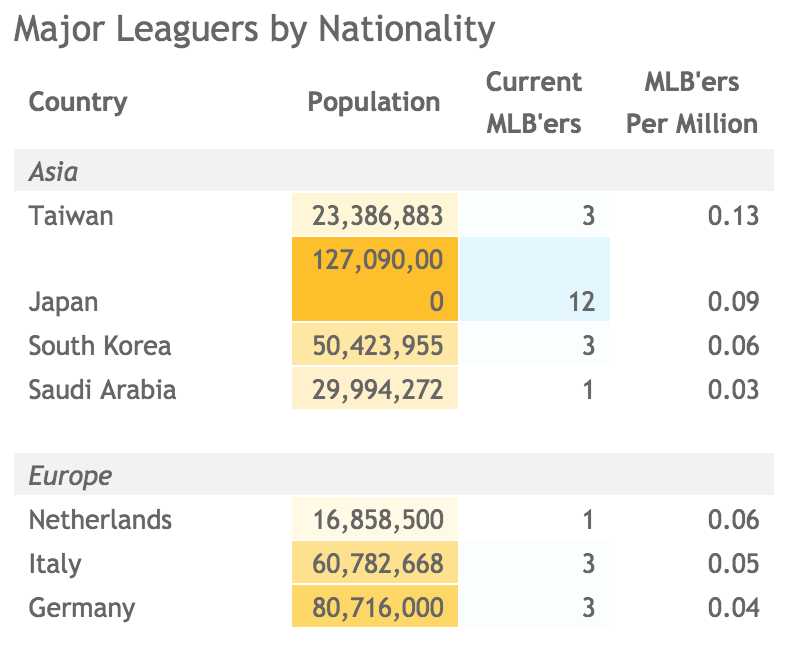

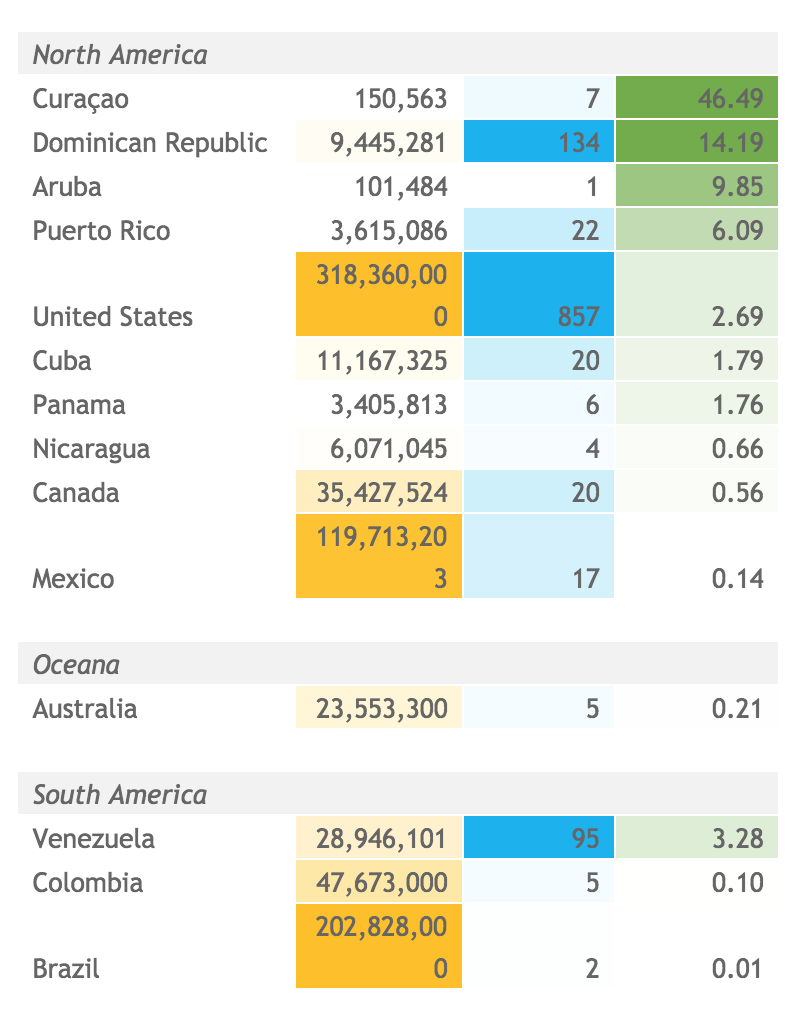

The above graphic is from 2014 and gives a good representation players from other countries. In 2019 MLB had 251 internationally born players which was the third-highest total in history, trailing 2017 and 2018. 28.5% is the fifth highest total in history.

(Image Source: https://uxblog.idvsolutions.com/2014/07/major-league-baseball-players-by-country.html)

It’s just as easy to find reading material on nearly world-renowned high schoolers signing huge multi-million dollar MLB bonuses as it is to find material on the consequences MLB scouts scouting 13 year olds.

The temptation to scout and sign younger players with multi-million dollar bonuses seems to pop the bubble of whether early specialization is actually worth it. The prospect of a multi-million dollar contract is quite tempting for players and parents. Whether they are an international player or desire to be a top draft pick.

Undisclosed in the success stories of specialization are the injury and failure rates. It’s quite common for players to either not make a team, be cut, or be hurt and not come close to signing a deal or even continue playing past their teenage years. The injury issue for pitchers is especially hard to track down, considering the difficulty in understanding why they occur in the first place, but overuse (or misuse) often gets pushed as issue number one. The issue of injuries related to specialization is not only a problem in baseball but also in basketball and other sports.

We know that if an athlete truly wants to play baseball professionally, he is going to have to specialize—it’s just a matter of when. USA Baseball’s LTAD recommends considering specialization around sophomore or junior year in high school. While we agree with this age, the skill level of the player should also be considered. Players who can play multiple sports and still be the best baseball player on their team may be able to specialize later. The part-time player who is determined to play in college and professionally may need to narrow his focus to baseball earlier than some of his or her peers. When athletes decide to focus on one sport depends on a number of factors including coordination, athleticism, evaluation of fundamental skills, and what their goals are. If athletes are going to try to play professional sports, then they are going to specialize at some point, you just need an honest assessment to tell them when that is.

All of which gets to the question of how an athlete can practice the specialized skills that baseball requires in order to get better but not go overboard. What complicates how much practice an athlete should have is a growing awareness of throwing and other workloads beyond just pitch counts, which we’re just beginning to notice what is valuable and what is noise.

More recently, technological and practical advances in areas such as pitch design raises the question of whether youth athletes should only focus on fitness, strength, athleticism and health in the hopes that those advances mean that the more technical skills can be refined faster at an older age. The skills required to be a pitcher are extremely specialized, which makes the question “How much practice do I need to get better?” more difficult to answer. Beyond general fitness and athleticism, youth athletes need just enough specialized skills to show that they can be improved. But even getting to that “just enough” level can require a lot of practice.

The question of whether specializing in baseball at a young age is the best way to do this becomes “Is the practice that I’m doing right now even making me better?”

A Brief Roadmap Forward

For youth athletes, the roadmap for long-term baseball success means two things:

– Having effective practices during the baseball season that focus on having fun and training skills that scale

– Building athleticism by playing other sports and lifting when it’s not baseball season

The most difficult part may not be looking for other sports to participate in, but finding time to learn the basics of weight lifting. While playing multiple sports has benefits, rotating from one sport to another can delay an off-season lifting program from after the season to never. If youth teams don’t have some sort of in-season strength program, we may be leaving kids further behind those that have one. This adds in another factor for parents and students to prepare for, and it still says nothing about the overlap and expanding schedules with various sports.

The baseball season can quickly turn into a spring, summer, and fall season. Travel teams increasingly having their tryouts immediately after the baseball season, in the fall, to lock players in and start practice in the fall and winter before the following season. While the intentions may be good, this can be replicated in other sports. This then can turn fall from just a football season into a football season with basketball once a week and bullpens on Sundays.

While this may seem like more of an issue for high schoolers than youths, we should expect these expanding schedules and team requirements to seep downward, requiring parents to put their foot down and say enough is enough. A multi-sport athlete can turn into a logistical nightmare in practice.

The Difficult Decisions of Youth Development

Admitting and realizing that the skills required to succeed in baseball are unique from other sports doesn’t mean that players should only play baseball. It just means that as players age, if they want to play baseball at a high level, they may need more targeted planning if they already aren’t one of the better players in their leagues. It’s also important to keep in mind that the success of youth baseball players matters little in the long run. Yes, they will have more fun if they are winning but winning shouldn’t be the sole focus. Giving athletes practices that are fun and engaging, where they can also track their progress, can be a good way to keep them playing baseball for a longer period of time.

It is true that the best athletes are going to be able to play baseball and other sports and succeed, that isn’t necessarily true for everyone else who isn’t the elite of the elite. Those athletes also need to be kept in mind.

So how can a youth baseball player, who wants to keep playing at a high level, get enough practice to be good enough to play at the next level while not being overused, while also realizing that every level becomes more difficult may require more specific practice?

It turns out that this is a much more difficult question than the simple suggestion of playing multiple sports.

Written by Operations Manager Michael O’Connell

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

EdAsh -

Excellent article. Nice work, Mike.

Pete S -

Great article and nice to see someone not dogmatically state that “specialization is killing youth sports.” In high school I played with a kid who made it to the NHL. In college I played with a kid that made it to the MLB. Both were such freakish, edge of the bell curve athletes, that no matter what sport they played, they dominated. For those types, have at it, play as many sports as you like, and dominate all. For the rest of us (and our kids), especially in hyper competitive baseball areas in the US, if you are not specializing to some extent by middle school, I just don’t see how you can “keep up.” No question, build fundamental skills early through multiple sports, but at some point, unless you’re that rare athletic freak, if you want a shot to be more than a recreational player, sorry, ya gotta specialize.

Dr.C -

Good article . More people who are involved with youth sports need to be on the same page with this. I see some kids develop injuries from playing too many sports without proper guidance then I see the other end of the spectrum. Specializing in one sport and becoming overused and burnt out. To split the difference and develop an athlete along the way while having fun is a very difficult task. I am glad you shed light on this subject.