Training Cricket Bowlers with Over & Underload Implements

This is a guest blog post by Steffan Jones decribing how he uses over & underload implements in his training to teach his athletes how to be better cricket bowlers. Steffan can be found at his website cricketstrength.com and on Twitter @SteffanJones105

The pitcher equivalent in cricket is the bowler. Bowlers are allowed a running start and must throw with their arm straight. To ease possible confusion we often refer to bowlers simply as ‘athletes’ in this post.

Making radical changes to a young fast-bowler’s technique too quickly is likely harmful to the bowler’s ability to develop and perform. Coaches (and parents!) who over-intervene and make changes before the bowler’s natural habits and love for the game develop are missing the bigger picture. It’s not about where bowlers are, it’s where they are going and how long they can stay there. Young bowlers are still developing neuromuscular control, and in particular during the “adolescent awkwardness” phase, they find coordinating movement difficult.

While there is no such a thing as one “perfect bowling technique,” there is a perfect technique for every individual. This is where coaches, players, and experts get confused. They mix up the parts that need a degree of variability with the nodes that need to be fixed to provide optimal movement. Identifying these and providing a systematic approach to intervention are the keys to a successful coaching experience.

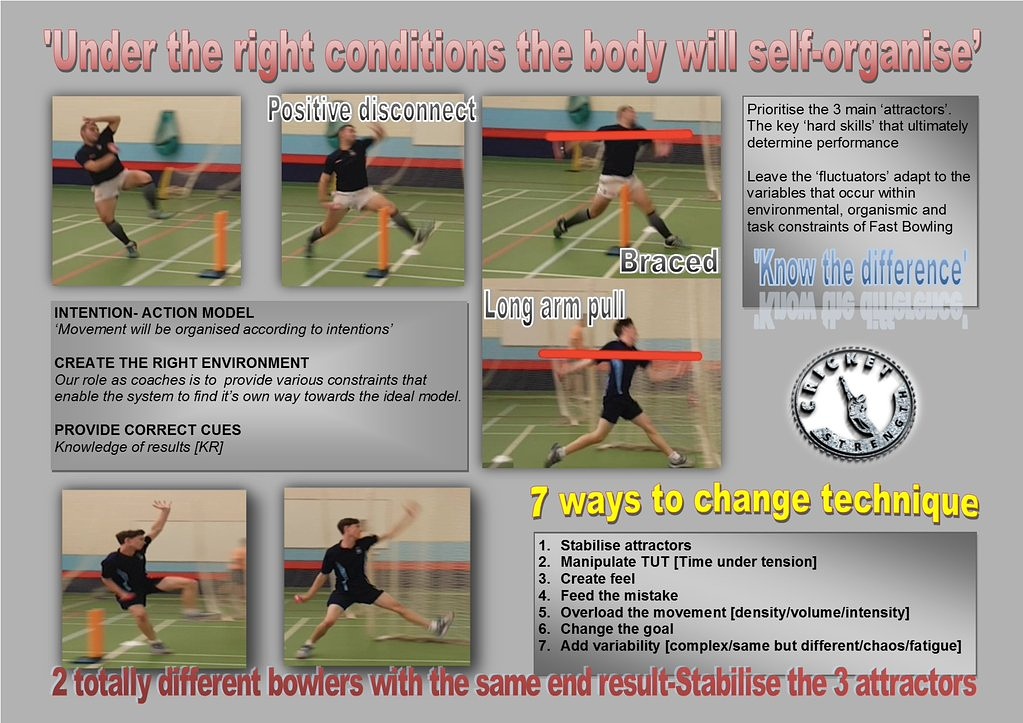

It’s not about building robots who bowl the same way; it’s about making sure the “attractors”which are the key basic, essential, fixed movements—are stable and reduce the degree of movement in the technical completion of the action. The individuality and idiosyncratic elements are the “fluctuators,”changeable components that have degrees of freedom that do not negatively impact bowling performance. Fluctuators help us adapt to the environment but are specific to individual bowlers. It’s their own method of organizing and adapting to the environment (self-organizing).

Effective coaching is about knowing what actually matters and identifying individual traits that don’t matter. Call them “attractors,” “hard skills,” “fluctuators,” or “soft skills”; understanding each is key to coach intervention.

Coaches should prioritize the hard skills because these are the ones most important to performance. These need to be taught early in the process as they are hard to break if bad habits set in.

Hard skills can be seen as the “sled on a snowy hill” phenomenon. The first rep is like a sled making tracks in fresh snow; after that first rep, it’s hard to make changes and the sled will follow the tracks.

These are the “big three” hard skills, for bowlers, in my opinion:

- Hip shoulder seperation

- Star position (long arm pull)

- Braced front leg

Performing these actions requires key parts of each sequence to fire accurately. While beyond the scope of this article, co-contractions around key joints that eliminate muscle slack, back foot contact, and pre turn—along with various reflexes such as crossed extensor reflex and stumble reflex—all have a direct impact on attaining each of the three hard skills. This is why technique should always come first in the intervention layer. Strength is built to maintain stability and transfer power from these key “attractor” sites that are specific to the skill being performed.

Understanding What to Look For

One of my most successful training concepts, known as “skill-stability,” respects the stages of learning and skill development while overloading the key attractor sits. These positions are influential to the success of the athlete. However the timing of each stage is a careful process that needs to be synergistically planned with the 4 stages of learning.

Overloading Technique to Make a Change that Becomes Unconscious

Improving performance is an art, and understanding how the brain works and how we learn are key. Drills for the sake of drills won’t work. Put those drills into a stressful environment to encourage adaptation, progression, and transfer to game readiness will work.

However, bowlers learn and improve at differing rates, and as coaches we need to respect the stages of motor-skill development and learning. The key to building the non-fragile athlete is to progress through these stages as quickly as possible while mastering each stage. Spending too long at the basic, unskilled level will fail to transfer to performance and ultimately lead to dropout.

You have to overload your technique for it to change. Adaptation craves overload. Just doing 10,000 normal repetitions won’t work—or may work at the novice level, but it won’t as the athlete gets older, has a higher training age, and becomes more skilled. First, boredom will kick in, making motivation to perform reps will low, and also the body will not find the need to adapt and change.

Remember, it’s done thousands of “poor” versions before. You need to stress the key positions. It’s more likely that the changes needed are relatively small, so doing something similar to what you’ve been doing will have little or no effect. Overload skill-stability training is the answer and, as a bowling performance coach, is essential.

Unless a coach overloads the athlete’s technique and encourages adaptation though stress in some form or another, all external queuing intervention methods are worthless—the changes simply won’t stick. The body and the brain have no desire or need to change.

When performing technical intervention work, I overload the action in four different ways.

- Density

- Volume

- Variability

- Intensity (weight or speed)

These methods encourage skill adaptation and skill progression, similar to learning a new language—in which you first learn the alphabet, then a word, then a sentence, then a paragraph, chapter, and finally learn to read a book. Learning to bowl fast (or pitch) is exactly the same. Skill acquisition and constantly encouraging and challenging the status quo will enhance the learning process. Stagnation and repeated technical work at a level that has already been mastered will ultimately lead to intervention failure or, worst still, player dropout.

Stress, Progress, Adapt, Challenge and Repeat

Too often we see coaches trying to change mechanics through the use of visual and audio commands (video and instructing) without first knowing how each athlete learns and processes information. This is based on Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), which describes learners as Visual, Auditory and Kinaesthetic learners. It differentiates how humans prefer to absorb information.

The reality is that unless the athlete is at such a low level of proficiency, the intervention doesn’t normally stick. Unless the movement is either overloaded through intensity (tempo/weight), volume (reps), or density (time), the athlete will have the same action for life.

Adding stress to the action when young is an ideal intervention method but needs careful planning and understanding. However one could argue that any new intervention method is too advanced for any level. All athletes regardless of skill level learn by the way of one or more of the modes of instruction. It is important to note that most athletes, around 80%, are primarily visual learners. They like to see what they are doing wrong. The coach’s role is to then prescribe the corrective method that will then allow them to subconsciously drill the right sequence. That is the ultimate aim. To allow the athlete to consciously focus on the completion of the skill with maximum intent while a carefully selected exercise does the coaching for them through various constraints. The drill is a subconscious coach.

How to Learn and Progress Through the Stages of Learning

There are four stages of learning and skill acquisition:

- Unskilled (Incompetence) – Unconscious

- Unskilled (Incompetence) – Conscious

- Skilled (Competence) – Conscious

- Skilled (Competence) – Unconscious

If takes every individual different overloading methods to move from one stage to the other. This is why the skill-stability model is tailored to each stage of learning.

Unskilled – Unconscious

The first phase of the skill-stability model is Static Stability. This involves using static holds in three of the basic kinetic sequence drills. There are four positions, but the static holds only use three: Back foot contact, front foot contact, and delivery. The follow through happens as a consequence of what happens earlier in the process and momentum, so static holds aren’t relevant.

This is the foundation phase of motor learning and change. The goal is to build strength through isometric contractions and overload co-contractions around key joints in the sequence. Each attractor site is held for 30-90 seconds to develop an awareness of those positions. What does it feel like to brace the front leg? What does it feel like to have your feet land under your hips? What does it feel like to have your hips square on and both feet pointing forward? At the early stage, the athlete has no idea what it feels like to achieve the key positions, being unaware of it. So, by creating feel, which is one of the main ways to manipulate movement, the athlete gains awareness and progress into stage two, becoming conscious of the positions.

My observations are that beginners (everyone who is trying to change technique is a beginner) attempting to do the skill-stability stage 1 exercises are simply going through the motion. Often they ridicule the exercises as pointless. In my experience, these beginners have been swayed into thinking all problems are solved in the weight room with a barbell. They can’t get the sequence together but still believe they are doing it right. They are highly inefficient at certain aspects of the actions. They are both unaware they are making a mistake and are unable to perform any intervention drill properly.

However, after time and effort, the training effect through time overload and creating feel, both physically and mentally, progresses the athlete through stage 1. Often with feedback from video, the athlete begins to recognize the difference between movement optimization (the underlying correct principles) and movement variability (what they can individually do that doesn’t negatively effect the positions). They self-manage and find their own way.

Unskilled-Conscious

The second phase is called Dynamic stability. Here, movement variability and external chaos are added to encourage adaptation and see organizing. With an added awareness of the key positions, athletes still find it awkward but are now aware of what is needed. Here various techniques are added while still holding the static positions of stage 1. The essential introduction at this stage is the “constraint” element of each drill. The athlete is locked/constrained into the position so as to encourage the subconscious grooving of the base positions while still maintaining conscious awareness of holding the positions.

Band perturbations static holds and force med ball absorption drills (catch and hold) are key ways to practice Dynamic stability.

By adding different stimuli, the athlete becomes more conscious and develops postural awareness that further engrains the positions due to a more challenging and dynamic movement exercise. Medicine balls are introduced at this stage to train the body to absorb force in key positions. After a few sessions and additional practices away from the session, the athlete begins to be aware of the inefficiency in his actions. He becomes conscious of the flaws but hasn’t quite mastered the technique to help improve the sequence. He knows what to do but can’t do it for a number of repetitions. He gets frustrated easily.

This, I feel, is an important stage. The athletes understand it but can’t repeat it. This is where they need to realize that they have to do the drills in their own time away from the structured sessions. Otherwise the new skill will never be automatic and stage 4 is just a distant dream—they are now conscious of being unskilled! Frustration, anger, worry, and boredom kicks in very quickly.

An organism isn’t interested in a stimulus it considers mundane. For effective learning to occur all non-reflexive stimuli must clear the RAS [Reticular Activating System]. This is in simple terms is the ‘ON’ button for the brain and motor learning

Doing the same mundane, non-stimulating drills without progression will never activate the “ON” button. This is why a lot of athletes fall out of favor with technical work. To turn the “ON” button to the “learning mode,” the athlete needs to be engaged and open to learn. This is where the art of coaching comes in, finding ways by adding variability to help athletes progress to the next stage of learning.

The key at this stage is keeping them engaged and motivated. You need to maintain the trust they have in your skills as a coach. Giving them a different stimulus keeps them engaged. The key now as they become aware is to make the next stage skilled, so as they become conscious and aware, they need to see the benefits—otherwise they will drop out. Adding chaos, feel, and by actually exaggerating the flaw, the system begins to know the difference between right and wrong. This is a great stage to really challenge the movement.

Movement can be manipulated in five ways:

- Manipulating time

- Creating feel

- Exaggerating the flaw

- Stabilize the attractors through overload (see above)

- Change the goal through external cues and providing knowledge of results

This is the stage where many athletes become very good at drill work, and terminating the intervention process here will develop a “fragile athlete.” They look good with the drill work, but it doesn’t transfer to on-field performance in an unstable sports environment.

This is the stage most athletes get to very quickly. To encourage progression and keep them stimulated, they will then progress onto stage 3 of the overloaded skill-stability model, in which variability becomes the key addition to the program. Up until this stage, volume, intensity, and density have been sufficient overloading mechanisms. We now need more advanced methods to progress from here.

Skilled-Conscious

Stage 3 is where the bowler now becomes aware of the positions. However over thinking and internalizing everything can become an issue at this stage, which is why stage 3 skill stability is about constraining the action and letting the drill do the coaching. This stage is about expressing the force potential developed in key positions into a more specific and ballistic movement. The power and speed phase which will transfer directly to game readiness. It is about using the stability developed in the first phase and the energy absorption and dynamic/chaos stability in the second phase and using it effectively and efficiently up the kinetic chain from proximal to distal. This phase is about learning to transfer energy up the chain and how to create hip and shoulder separation.

The following exercises become ballistic in nature and highly specialized:

- Med ball throws

- Level 4 kinetic chain sequencing and constraints drill

- Grooving weighted-ball work

- Constrains positive disconnection bowling (hip lock drill)

- Velocity weighted-ball bowling

However, constraints still form the structure of the drill work. Learning occurs through the part-whole method of motor teaching. After learning the constrained part of the action, the whole action is performed. Keeping this window of transfer small increases the probability of positive transfer. Superseding a drill work with the full action at a batsman or into targets will encourage learning, forming the basis for the next stage of the skill-stability model in a circuit/complex fashion.

There are two factors that influence transfer:

- Movement – result similarities – the intention action model.

- Sensory similarities – specificity of practice effects the sensory feedback. Motor control is based on the link between sensory input and motor output. Movement learning is highly specific to the sensory feedback during the session.

Sensory feedback is key. For example, when drilling there needs to be a focus on dragging the back foot from position three to four. What I tell my bowlers is to pretend to scrape mud off the front of their shoes. The subconscious mind is radically different from the conscious mind and the more immature and silly the cues the better.

Having reiterated that they must keep doing the drills away from the sessions, the athletes begin to consistently repeat the technical sequence. However, at this stage they have to remind themselves and cannot subconsciously perform the drill. They have to tell themselves to pre turn, brace front leg, square the hip, etc. This is the most important stage of learning the new technique. At this stage, they are aware of what they are doing but don’t see it when perform, for example. A lot of players get stuck in this phase because they have to “think”; they have to mentally control the movement. This stage requires patience from both the coach and the athlete. The easy thing to do here is dismiss the drill as being pointless and ineffective, but the key point to remember here is that you’re/they’re getting closer. Keep believing in the process, and the results will come.

From experience, as a coach and as a player, coaches need to be aware that between stage 3 and 4, frustration will occur. This is the stage where athletes begin to doubt and blame external factors outside of their control. They start thinking too much. Evidence suggests once a player reaches the SKILLED-CONSCIOUS stage, thinking actually interferes with skill execution. So this is why the exercise needs to do the coaching for them. Corrective strength and constraint drilling are key to the success of this stage.

Skilled-Unconscious

The final stage of skill acquisition is stage 4. Here, as coaches, we will be able to observe athletes who’ve mastered the skill! When they go through the kinetic chain sequence, they can do it without thinking. This is when as coaches you’ll know you’ve made a technical change and a difference to their game. You have had an impact on that young athlete’s career. At the end of the day, that’s why we coach. It’s to have an impact and make an impression. They trust us to help them.

However this stage is now about manipulating the environment and recreating situations that occur in game situations. This stage is about tactical awareness and maximum performance transfer. Here “tactical periodization” integrated with skill-circuits are planned and performed during this stage of learning. It’s about replicating key moments of the game in training that prepare the athletes for when the situation occurs in competition. Complex training for the PAP effect supersetted with maximum intent during an initial part of the game is performed. Tempo blowing at 70% intensity utilizing fatigue as a great learning tool is also used along with a skill circuit combining isometric drills, ballistic drills, and anaerobic exercises, contrasted at the end of the game when performance is very much dictated by fatigue and is also replicated in training. This stage of learning is highly advanced, and the methods used are based on sports science at the elite level.

Conclusion

As coaches, we need to tailor our sessions to cater for the needs of individuals and where they lie on the stages of learning. Athletes cannot dwell on a drill if they have already mastered it. Holding an individual back merely to make the organization of the session is a habit I’ve seen on a number of occasions in professional sport. Athletes learn at different rates, and we need to move them along as quickly as possible to stage 4, skilled conscious, where transference of training will be more physically, tactically, and mentally determined. Coaches need to design a system of coaching based on the synergistic partnering of skill-stability training and the stages of learning that helps fast bowlers (or pitchers) develop and progress at a rate that is individual to them. Athletes don’t want to be driven by technique, so as coaches we need to be smart in what we prescribe and how long they stay with each exercise.

Don’t drill for the sake of drilling. Don’t go back to the beginning. When you know the alphabet you don’t revisit it if you’re reading Shakespeare.

I fully appreciate that technically drilling a bowling action is both tedious and a long-winded process, both for the player and the coach. Often the coach feels he’s taking the easy option by just standing back and letting the player do the work alone. If prescribed properly, the only coach athletes will ever need is the constraint drill itself. You are now redundant! What we must realize as coaches is that leaving them learn themselves is actually benefitting them more than we appreciate, and just letting them learn by doing is the best thing we can do. However, technical reinforcement work still has to be done. As coaches we need to sit back, manipulate (add constraints), monitor, observe, and guide them when the sequence isn’t correct. Coaches need to be aware of the constraints that occur during skill acquisition. The challenge for coaches is how to integrate the vast amounts of sport science information, difference of opinion, and methods into their training and competition programs to the benefit of their athletes.

Comment section