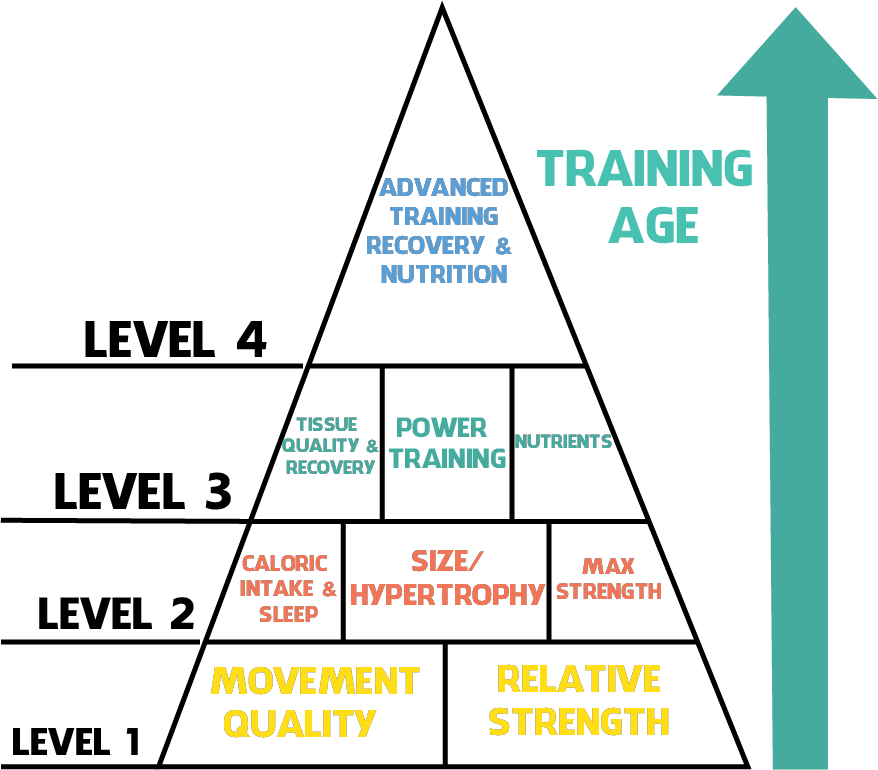

A Hierarchy of Training Needs for Baseball

It seems that only strength and conditioning professionals are the ones who get fired up watching highlight videos of the fundamentals, like the well-executed squat or a technically sound hip hinge.

For much of the rest of the sporting world – those that didn’t go to school to learn the intricacies of sport performance – the fundamentals don’t carry the same weight or appeal. This is understandable. There’s nothing sexy or appealing about building the foundation – not in baseball, not in home design, and certainly not in training. We want courses specific to our college major, not general education classes that everyone must take. We desire to shop for home décor, not pour concrete. We ask for batting practice on the field, not tee work in the cage. We seek instant sporting gratification, not long-term athletic development.

But, in terms of an athletic career, it’s in the fundamentals that the majority of training exists. And, it’s in the basics that the bulk of progress and development exists.

To move beyond the basics is to begin living in the margins of training. This is a necessary part of the training timeline, but it is only part of the timeline, and a later part at that. Typically, it is the athlete who has reached the “elite” or professional status that must chase marginal gains.

The Aggregation of Marginal Gains

This process is called the aggregation of marginal gains. In other words, for the advanced athlete/trainee, we are attempting to uncover and summate every last ounce of progression. By discovering every miniscule advantage to be had from training, recovery, nutrition, psychology, etc. we are hoping to attain as many fractions of a percent in increased performance that we can. If an elite athlete can improve by 1% overall in a year, that’s pretty good considering they’re already in the 99th percentile of athletic performance. Yet, it’s in the fraction of a percent where we find the line between winning and losing at the highest levels of sport.

In training this is where the most sophisticated methodologies, protocols, and implements come into play. From bands and chains, to highly reactive jumps and throws, advanced and high-frequency recovery methods, and the minutia of nutrition. Not to mention individualization and customization of every aspect of training.

With a training age anywhere between approximately 5-20 years, the elite athlete has very different training requirements than the novice athlete with, say, 0-4 years of training experience. This is because, over time, the body’s response to a dose of training yields diminishing returns in terms of adaptation. In the first few years of training, minimal “dosages” or exposure to training loads yields great returns. Over time, these returns diminish; a point of inflexion is then reached, and thus much greater stimuli must be used to propagate adaptation.

So, why should a novice trainee – i.e. the amateur high school baseball player – chase fractions of percentages when bulk progression can be easily achieved with a more broad focus; move well and get stronger.

Unfortunately, many coaches and players do not even realize that they are chasing marginal gains. They do not know any better, thus they are compelled to utilize training methodologies that either, a) are used by the professionals (if it works for them, it will work for me, right?) or, b) are more appealing to them.

But, “not knowing any better” doesn’t have to be a fall back excuse if we can educate the amateur coach and pitcher, and that is what this post seeks to accomplish.

The goal of this post is to provide a framework for understanding the progression of training methods and the varying importance of training characteristics and methods over time – in other words, a hierarchy of baseball training needs.

The Hierarchy

Level One:

The base of the above pyramid represents the foundation of the hierarchy, and as you can see, the foundation is composed of very few aspects. The first is movement quality.

It is essential that the athlete meet a certain standard of movement competency in every movement category deemed vital to improving sport performance. In the case of my own philosophies, I believe that the Squat, Hip Hinge, Tri-Planar Lunge, Upper Body Push/Reach, and Upper Body Pull, are all integral parts of the program. The athlete must be able to perform the base regressions (e.g. the bodyweight squat or push-up) of all of these exercises before there is any need, desire, or capability of advancing to more challenging exercises. This doesn’t just mean that the athlete obtains the strength necessary to perform the movement, but also the coordination, pain-free range of motion, and postural awareness to perform it safely and effectively.

Likewise, a standard of relative strength is a critical stepping stone on the path to more advanced training methods. Without the ability to control and move one’s body weight with grace and ease, who’s to say that the athlete can move any kind of load without getting hurt – let alone with that same grace and ease.

The other reason movement quality and relative strength make up the foundation of the hierarchy is because training for these, alone, can be enough to yield great adaptation. As was stated above, greater returns on investment are made in training when the athlete has a lower training age. Thus, we do not need to worry about other factors or outcomes at this stage of training.

Level Two:

As the training age progresses other factors must be taken into consideration when training the athlete. Although any athlete can get improved performance in the first year or so without worrying too much about nutrition, recovery, or other aspects of performance enhancement, the intermediate trainee must now address these aspects to avoid greatly diminished results.

The second level of the hierarchy consists of hypertrophy and maximum strength, caloric intake, and sleep. As strength gains yielded as a result of early neurological adaptations begin to taper off by this point (the new trainee gains a lot of relative strength thanks to neurological adaptations and improved coordination), lean muscle mass and loading parameters begin to present as limiting factors for development. In other words, without attempting to expose the body to greater loads or volumes, or without increasing lean body mass, the body can only get so strong as a rapid rate. Maximizing strength and power while maintaining the lowest body weight possible is an art and science unto itself reserved for Olympic weight lifters, wrestlers, and the likes, not the baseball player or pitcher.

Therefore, if the amateur baseball player wants to attain the greatest improvements in performance over time, an increase in maximal strength will certainly help. To help increase maximal strength, an increase in lean muscle mass must be achieved, and to facilitate hypertrophy, caloric intake must match that goal. Sleep, too not only impacts performance directly, but it also is the window for which adaptations such as hypertrophy occur. Thus, over time, sleep becomes increasingly important to manage as an aid to recovery.

Level Three:

As we progress in chronology and up the hierarchy of baseball training needs, it is important to understand that by looking at the pyramid, we can not only see what we need in order to maximize performance, but also what we don’t necessarily need. As a beginner we don’t need to worry as much about sleep. Is it important? Of course, but is it vital to see great gains as a beginner? Not entirely.

At the third level of the hierarchy, the athlete is a few years into training and now must orient themselves toward the more minute and fine aspects of training to experience optimal results. For example, the quality of calories and nutrients consumed, recovery modalities, tissue quality, and some methods for training for power must be utilized.

This isn’t to say that training for power shouldn’t occur earlier in the training career. Nor does this mean that the quality and quantity of food consumption doesn’t matter to the novice trainee. But, what it does mean is, at this point in training, to see performance gains we need to start living in the margins.

In earlier stages of development and training, power output was most likely increased simply by improving strength, physical and performance goals were probably met by ensuring adequate caloric intake, and the body probably recovered well enough from a few consecutive nights of quality sleep alone. But, as the athlete chugs his or her way toward higher-level competition, these methodologies will provide diminishing returns.

Level Four:

Finally, the upper-most level of the hierarchy of baseball training needs points toward the most advanced methodologies. Oftentimes, this is where the veteran MLB’er receives treatments and training that simply allows performance at all. In other words, they are there to prolong a baseball career. To be frank, very few will ever need to know this level of the hierarchy.

It must be emphasized and understood that the hierarchy of baseball training needs is not meant to pigeonhole an athlete into one level (and therefore, into only certain training methods) based upon their training age. It is designed to help provide a framework for understanding of what the minimal dosage of training is required to see maximal gains in performance over time.

If I may, I will pose one example to drive home this point:

Imagine an incoming freshman athlete comes to me – a high school strength coach – and I give him or her the most advanced training that I can think of:

- The French Contrast Method

- Rigorous soft-tissue work

- Strict and clear-cut eating regulations and a meal plan

- And have him/her do recovery sessions each day

Now, ask yourself the following questions:

- What do we expect adherence to that program to be? 100% with no mistakes or lapses?

- What do we expect the injury rate to be?

- How likely is the athlete to burn out and quit?

- What on Earth is this athlete going to be doing by the time he/she is a collegiate athlete, after doing all of this as a young high school athlete?

- Why do all of this when we can invest much less effort and time, but get relatively equal results in the early stages of training?

Understand that, by building the base, you will only increase your likelihood of sustaining a long enough playing career to get to the advanced methodologies. And, if for whatever reason you don’t play long enough to reach the advanced methods, you can always do all of the fun and sexy stuff when you’re out of the game and performance outcomes don’t matter anymore.

Comment section