A Guide to Strength-Training Progression – Part III

In Part I and Part II of this three-part series we discussed the importance of progressive overload, and the use of exercise/movement progression and training intensity as means to achieve it.

For the third installment we will cover the meaning and significance of training volume to the overall training program, and how to go about using it to manipulate training adaptations to achieve your training goals.

The Principle of Specificity

In order to grasp just how significant training volume is, another training principle must be mentioned in addition to progressive overload: specificity.

Although progressive overload is getting all of the mentions and love in this series, the principle of specificity is equally important.

Specificity essentially means that you get what you train for. The inverse is also true: you don’t get what you don’t train for.

- If you want to get faster, you have to train to run fast.

- If you want to get bigger, you have to train to get big.

- If you want to throw harder, you have to train to throw hard.

I am aware how incredibly obvious this sounds, but if you really think about it, you have probably witnessed many people neglecting to adhere to this “basic” concept as they go about their training.

This isn’t to say that we should only train exclusively for the most obvious characteristics of our sport. For example, to say that pitchers should only run sprints because they need to train fast to throw fast is taking the specificity principle so far as to forget that other bioenergetics are at work in baseball and recovery (more on this in my next post).

But, by using the principle of specificity, we can determine which traits are most desirable for our sport, which will allow us to focus our training in order to emphasize stimuli that will achieve the appropriate adaptations.

Training Volume

Now that we understand specificity, let’s take a side-step to define training volume:

Training Volume = Sets x Reps

You can also evaluate the Load Volume by:

Load Volume = Sets x Reps x Load

Either way, the goal is to track and manipulate how much work is being done during any one training session.

On the surface, higher and lower training volumes generally elicit different outcomes. 4 x 12 and 4 x 5 are two different schemes used to apply varying stress, where the former having a goal of hypertrophy or endurance, and the latter strength.

Repetitions and maximal loads capable are inverse of each other. The greater the reps desired, the less the potential is for load. Thus, higher repetition sets, such as 15-20 are used at very low training intensities. Conversely, lower repetition sets of say, 3-6, are generally performed with substantially greater loads.

With this in mind, you can start to see how training volume can be manipulated to create progression. But, first we also understand how training intensity can have an impact on the outcome of the volume used.

Training Volume and Intensity

It isn’t always as simple as calculating your sets x reps and altering the program from week to week in order to create progression. To illustrate my point, check out this example:

3 x 12 and 12 x 3 both equate to a training volume of 36.

Yet, when we perform 3 x 12, we are generally using lower intensities and short rest periods with the intention of inducing muscular damage, ultimately stimulating hypertrophy.

12 x 3, on the other hand, could generally involve either moderate loads and varying rest to train for power and speed, or even heavier loads and longer rests to train strength and power.

Thus, training load, alone, is not always enough to track progression. This is why load volume is used quite often to track overall training volume more accurately.

By understanding training volume and its relationship with training intensity, you can start to get a better picture of how to progress training on paper (why do I say, “on paper?” …more below).

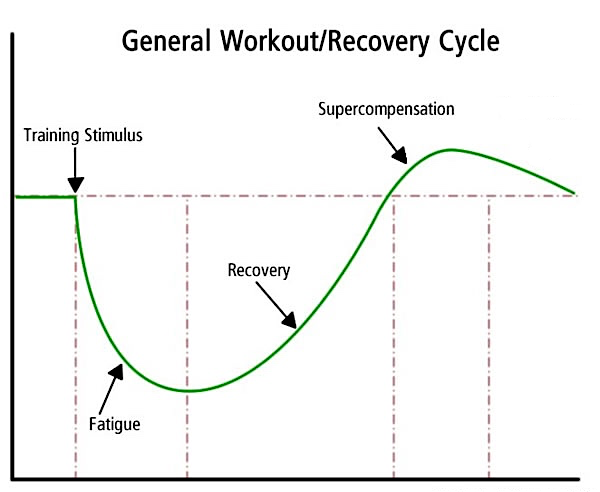

Training volume and intensity need to be manipulated, not only to facilitate gains in the off-season, but also to allow for tapering and peaking in-season. Tapering refers to the method by which the training program’s volume and/or frequency is progressively unloaded as a major competition closes in. We do this in order to allow the body to recovery and supercompensate.

Although every game is important, some may carry more significance than others. If we took the foot off of the gas pedal for every game during the baseball season (or every week), we wouldn’t get too much accomplished in terms of performance enhancement. So, to ensure improvement in-season and readiness to play for the most significant games, we can back off of the training volume and/or frequency as the competition nears.

For example, as the playoffs approach, training volume can be reduced progressively in the 3 weeks leading up. The intensity would still need to be kept high (heavy loads), but the volume would significantly decrease as to reduce the amount of muscular and neural fatigue accumulated, and to allow full recovery and supercompensation so that performance “peaks” when it matters the most.

As mentioned above, though, this is all great on paper, but another aspect can and should be considered when using volume and intensity to elicit positive training adaptations.

Exercise Progression and It’s Impact on Training Volume

Now consider how difficult an exercise is, and how that relates to its training volume. One obvious example is the difference between 4 x 6 on a Back Squat versus 4 x 6 on Leg Extensions in terms of stress on the lower and total body.

Some even more subtle, yet enlightening examples would be:

- Full Deadlifts vs. Concentric-Only Deadlifts

- Pause Deadlifts vs. Speed Deadlifts

- Deadlifts vs. RDLs

- Conventional Deadlift vs. Sumo Deadlift vs. Trap Bar Deadlift

All things being the same, the amount of stress and its emphasis on the body will differ depending on the varying stimuli associated with these kinds of circumstances.

In Summary

When speaking about progression in performance training, there are many factors to consider, including training volume, training intensity, and exercise progression. In this three-part series we have thoroughly discussed each of these parameters.

But, to isolate any one training parameter would be a serious miscalculation of how each factor plays off of the others.

For example, to isolate training intensity would be nearly impossible, as intensity and volume are highly interdependent. Likewise, exercise difficulty/variation can have an impact on both volume and intensity. Hopefully this series has also done an adequate job demonstrating these kind of relationships between the training parameters discussed.

There are also other ways to progress training in addition to those mentioned in this series, such as frequency and duration, time under tension, and type of resistance utilized. Just because they were not mentioned here does not mean that they cannot make a big impact on training, and ultimately performance. You will just have to do some more reading.

One of the greatest limiting factors of training is the willingness to seek out more knowledge. The more you know, the more you grow.

Comment section

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

A Guide to Strength-Training Progression – Part II - Driveline Baseball -

[…] author: Ryan Faer […]