The search for missing pitches. Are we early or late in the evolution of pitch design?

In each recent season we have witnessed a trendy pitch proliferate pro baseball.

We saw the sweeper spread across baseball in 2022. The pitch made headlines regularly as it spread from places like the Driveline, and the Dodgers and Yankees organizations, to throughout baseball. GIFs of the darting, horizontal breaker appeared on a nightly basis.

Whether some of these new labels represent new pitches is a point of contention for some. Sure, it’s possible Christy Mathewson was throwing sweepers in the 1905 World Series. Throughout history select pitchers have certainly possessed big, horizontal curveballs. But what changed – what is new – is the ability to scale pitch shapes thanks to the marriage of pitch-tracking data and high-speed cameras, creating the field of pitch design.

There is much less searching in the dark for the ideal movement profile, for the right grip.

This year, we have heard often about the kick-change, a variant of the changeup.

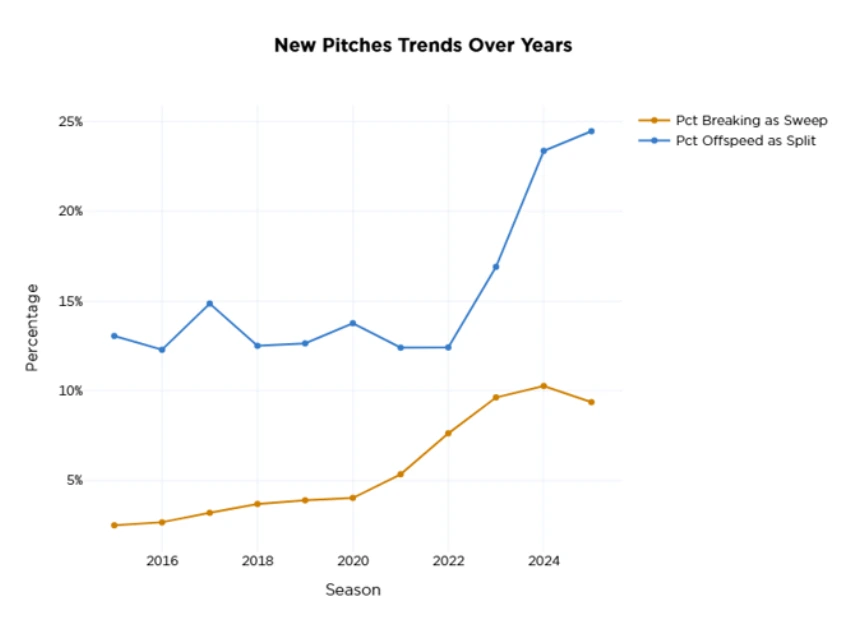

Last season, it was the year of the splitter, a pitch which Driveline had a hand in accelerating.

While pitchers had deployed the splitter at a double-digit usage rate for years in Japan, it was placed on the endangered species in North America due to injury fears. Even the open-minded Twins starter Joe Ryan initially balked at the idea of the split-changeup grip when he picked it up training with Driveline during the 2022-23 offseason.

“I was super apprehensive initially,” Ryan told me when reporting on his experience.

The success Ryan had with the pitch played a role in its greater adoption throughout baseball. MLB splitter usage has doubled from its 2022 level.

These advances in pitch design have filled voids in the pitch movement plot. It led me to wonder what is next in pitch design. What is the next pitch that will spread throughout the game? What shape is missing? Is there another pitch movement profile to be created? Or has the science of pitch design solved most pitches that are possible within the constraints of the physical laws of the baseball universe?

In beginning my quest, I visited the Kansas City clubhouse and asked Royals pitcher Michael Lorenzen, who has experience training with Driveline.

“We are trying to figure out what else is there,” Lorenzen said. “The high-vert cutter, those are really valuable. We haven’t figured out how to create that spin consistently, and to do that from different slots.

“That pitch and the hybrid four-seamer from (lower) slots, too. … Max vert. It’s been a pitch that’s so hard to do, especially for me. In my own personal case, those two pitches have driven me crazy a little bit.”

I posed the same question to Zach Bove, the Royals’ director of pitching strategy and assistant major league pitching coach

“The shape that we’ve talked about, we inherently just call it like a ‘float cutter’,” Bove said. “Think of a cutter but it’s got a little bit more turn to it, but maybe not cutter velocity. It’s slower, maybe a mid-80s pitch, but it’s got vert. You’ve heard about the ‘Hand of God’ sweepers, right? They’re big. So, it’s like almost a mix between that and like a regular cutter. That’s something that (Seth) Lugo‘s played around with a little bit.”

Cutters with substantial vertical movement are a missing profile.

Consider that of 267 pitches to throw at least 25 cutters as of mid-September this season, only 57 had double-digit vertical movement with the pitch. And only two had 15-inches or more of vertical movement. One of those high-VB cutters is a signature one belonging to Kenley Jansen, a pitch that has made him one of the best high-leverage arms of the modern era.

Other missing shapes?

Bove mentions a shape that is missing on almost all movement plots, and that is tied to a pitch that has nearly gone extinct.

“You have that screwball-ish area that not many guys can accomplish,” Bove said. “So, I think that’s maybe the other pitch.”

Could the screwball, something of a reverse breaking ball, make a comeback?

According to pitch-classification data, only seven screwballs have been thrown this year, and they all belong to Noah Davis. There were 153 in 2024, most credited to Brent Honeywell, a modern outlier to throw the pitch.

Gone are the days of Carl Hubbell, whose screwball was the stuff of legend – a signature offering fueling a Hall of Fame career.

One of the reasons the pitch disappeared was perceived injury risk related to its usage, just like the splitter.

Due to unusual motion required to throw the screwball, the pitch that was said to have deformed Hubbell’s throwing arm. Hubbell and about everyone else blamed the screwball on an offseason surgery he endured in 1939 to remove loose bodies from his elbow. He felt it hastened the end of his career.

But SABR’s Warren Corbett challenged conventional thinking in a 2011 piece titled “Hubbell’s Elbow: Don’t Blame the Screwball”

Wrote Corbett:

“Although the American Sports Medicine Institute has no data on that rare bird, the screwballer, Glen Fleisig told me, ‘The screwball is harder [to throw] but I don’t think it’s more stressful.’ He acknowledges it may hurt more than throwing a curveball—that’s why most people think it’s more damaging—but pain does not necessarily equal injury.’

“(Mike) Marshall said: ‘Throwing screwballs is safer than throwing pitches that require baseball pitchers to supinate their pitching forearm through release.’ …. Marshall threw his screwball more than one-third of the time, far more often than Hubbell. He has never had arm surgery.”

Driveline pitching coordinator Matthew Kress shared a fascinating idea regarding the disappearances of the pitch: it might not be dead after all.

“It’s magically kind of disappeared. So, I had this theory in my head. I was like ‘Is it actually living among us and we just don’t know?’” Kress said.

A ghost pitch?

The thought arrived when Driveline opened its new training facility in Tampa, Fla. and former Driveline staffer David Howell, now a coordinator with the Phillies, toured the facility.

“We bonded quickly over a passion of pitch design,” Kress told me. “I asked (Howell) ‘What is the one thing that is really hard for somebody in my scenario, outside of a major league organization, to figure out? He got me on this seam orientation kick. Screwballs are mostly, in my opinion, probably changeups that fall below the zero VB line, and the scary thing is there are actually, like, a ton of them among us.”

In analyzing pitches with zero to negative vertical break and eight-plus inches of arm-side run – like Honeywell’s screwball – there have been more than 20,000 such pitches thrown in each of the last two seasons. There have been 124 individual pitcher to throw such a pitch this year alone.

Logan Webb’s seam-shifted changeup, for instance, meets such criteria.

“There are a ton of people, even (A’s first-round pick) Jamie Arnold, who technically speaking throws a changeup that would be in a category of like a right-handed curveball or slider,” Kress said. “If I were to start putting some classifications on things, (a screwball) is a changeup that is able to get negative VB or drop.

“And the more that people start to figure out how to affect seam-orientation changes, and actually get it to drop more, they are actually starting to flirt with what we thought was a screwball.”

If and when more seam-orientation data becomes public, data from Hawkeye, then pitch design could take another step forward.

But even then, there are probably not that many dramatically different shapes to design and scale.

That means the next phase of pitch design is about something else.

“I think the individualization piece is really important,” Bove said.

While recent years have been known as the year of a particular pitch, pitching analyst Lance Brozdowski dubbed 2025 as the “year of the pitch mix.”

It speaks to the idea that a lot of the necessary pitch shapes have already been created, solved as scale. It means the focus now is on employing pitch design to better individualize a pitcher’s arsenal, fill in an individual’s skill gaps, and complement primary offerings.

A related Driveline advancement in shaping arsenals and pitch design are the Mix+ and Match+ scores created Jack Lambert.

Match+ compares how similar pitches are coming out of a pitcher’s hand. The higher the score, the more the pitches mirror each, and create swing-and-miss.

Mix+ evaluates how distinct the pitches are out of hand. These are pitch pairings designed to surprise hitters. A high Mix+ should result in more called strikes.

Pitchers, ideally, have both traits in their arsenal to complicate swing decisions and generate whiffs.

“I don’t know if I have a single pitch type that I think is underutilized, but I think, in general, for each specific pitcher a different pitch type could serve them well,” Lambert explained.

For example, last offseason in pouring over Trevor Rogers‘ pitch data — Rogers worked with Driveline last offseason — Lambert noticed that much of Rogers’ arsenal had excellent Match+ scores but poor Mix+ scores. As a result, Dylan Gargas worked with Rogers on developing a sweeper.

At the recent Saberseminar, Lambert, Josh Hejka and Marek Ramilo made a presentation about the state of pitch design. Much of the focus today is on the process of individualizing arsenals. As part of the presentation they shared how they evaluate what types of pitches a pitcher can throw, and decide what to add based upon expected outcomes of a pitch’s profile.

Some examples from their presentation:

Hejka adding a rising slider to get whiffs from his submarine slot.

Andrew Hoffmann altering his changeup to something he can better command in addition to boosting its stuff.

John Schreiber adding a cutter to induce more swings and weak contact.

Another example is Paul Skenes.

The Pirates’ ace was not in obvious need of improvement coming off a remarkable season. But last winter he tinkered and expanded his arsenal to add a cutter and sinker with the goal of inducing more weak contact. The hope was to work more deeply into games. He set an ambitious goal of throwing 240 innings this season.

I spoke to Skenes in the spring about adjustments to his arsenal.

“It was just noticing things throughout the season, like, ‘Dang, it would be nice if I had this,'” Skenes says. “And at the end of the year we had a meeting, folks came me to saying, ‘Hey, we think this would be good for you to implement.’ Frankly, it was all stuff I had thought of, but they showed me the objective and the numbers, and projections and stuff like that, that showed it would work if I executed it.”

While he didn’t did not reach his ambitious innings goal, he jumped from 160 total innings in 2024 to 181 innings with likely one more start before his season concludes.

If one of the best pitchers in the game is going back to the drawing board every offseason to evaluate how he might add to his pitch arsenal that means every arm ought to have a similar curiosity.

There might not be many new shapes to discover in the field of pitch design but that does not mean the field is not advancing. When it comes to the individualization of arsenals we are just getting started.

Comment section