Trevor Rogers’ comeback is a classic Driveline success story – with some new wrinkles

Trevor Rogers heard the noise.

Just weeks after last summer’s trade deadline deal to acquire the lefty from the Marlins, many declared the Orioles had already lost the trade.

Rogers struggled with his new club last year, and began this season on the IL. Adding to the Baltimore fans’ ire was also what they gave up in the trade: Kyle Stowers, enjoying a breakout season, and Connor Norby, a promising third baseman.

For many, Rogers became representative of the team’s recent struggles, their falling short of expectations.

But no one was more disappointed than Rogers.

That disappointment advanced to become fear late last season when his velocity continued to diminish, including fastballs that were failing to reach 90 mph in his last starts in August. He was demoted to Triple-A Norfolk to end the season.

He had no idea why his velocity was declining, and his performance along with it.

He was moving further away from his 2021 breakout when he posted a 20.2 K-B%, 2.64 ERA, and 2.55 FIP. Entering this season, he had combined for a 5.09 ERA and 1.52 WHIP in 249 innings since his all-star year. It was a three-year span interrupted by multiple injuries.

Was he ever going to get back to being a top-of-rotation arm?

He was hesitant to visit Driveline in the past.

“I thought they were just going to give me Plyo(Care) balls and do this, that, and the other,” Rogers told me. “That’s why I kind of naively didn’t go (before).”

But after last season he was desperate for answers. With a nudge from Marlins bullpen coach Brandon Mann, Rogers traveled to Driveline’s Arizona facility in early November.

It wasn’t what he expected.

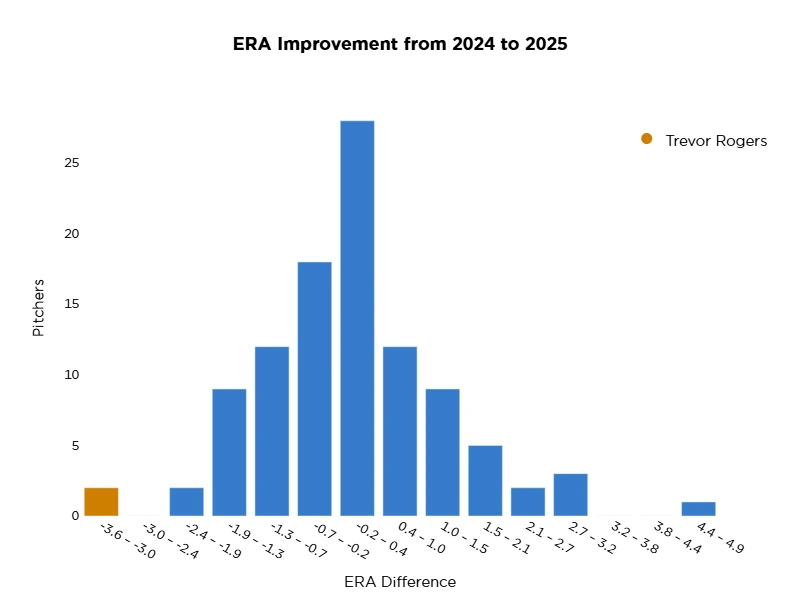

This season, Rogers is one of the best turnaround stories in the majors, posting a 1.44 ERA through his first 10 starts. He owns the second best year-over-year ERA improvement (-3.48) among pitchers that threw at least 40 innings last season, and 40 this year. Only Taijuan Walker (-3.57) owns a greater ERA improvement.

In many ways it’s a classic Driveline story, but one with some new wrinkles.

This is a story that begins with strength.

Rogers’ first visit to Driveline at the end of October was unusual in that he didn’t have a motion capture of his delivery completed because he was shut down from throwing.

But a mocap was not needed to understand a key underlying issue: he had lost considerable strength.

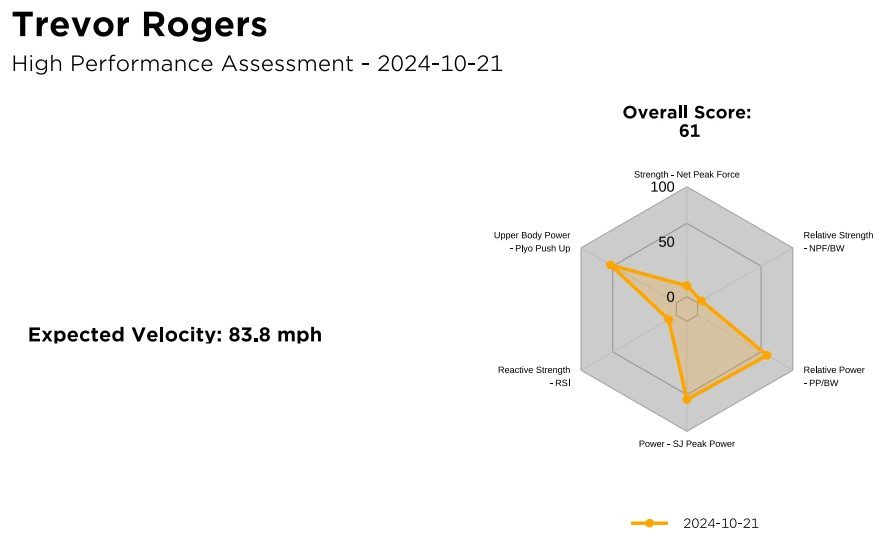

His overall strength assessment score was 61. Most pro pitchers who visit post scores in the 80s.

His strength was so low it projected him with an 84-mph fastball.

But Rogers was actually pleased with the test results.

Why?

“It was like ‘Thank God.’ I was thankful we found a problem,” Rogers said. “If we didn’t find a problem, I was going to be like ‘What do we do now?’ It was more of a relief. This is what is causing the issue, the dip in velocity.”

It wasn’t a total shock to some in his camp.

In their initial meeting with Driveline staff, Rogers’ agent said his client “filled out his pants” better during his all-star season in 2021.

Rogers had a particularly weak lower body as he’d moved away from certain routines.

“He had the back issues starting a couple of years ago and he really just avoided doing a lot of things in the weight room out of fear, or, just to stay healthy and stay on the field,” Driveline Arizona High Performance Coordinator Tyler Kozlowski said.

The challenge was creating a strength plan to address the underlying weakness with drills that would not risk another back issue.

The solution?

Rogers said he avoided barbell squats as Kozlowski prescribed “a lot” of dumbbell routines. “Split-squat dumbbells, goblet-squat dumbbells,” Rogers said.

He was given a training regimen by Kozlowski that slowly built the first three weeks and ramped in intensity from there.

Said Driveline pitching coordinator Dylan Gargas: “Just seeing those gains in the weight room, that progress can be pretty addicting and also be a momentum shift, a tidal wave. It’s almost like that can carry over to the throwing side.”

And it did.

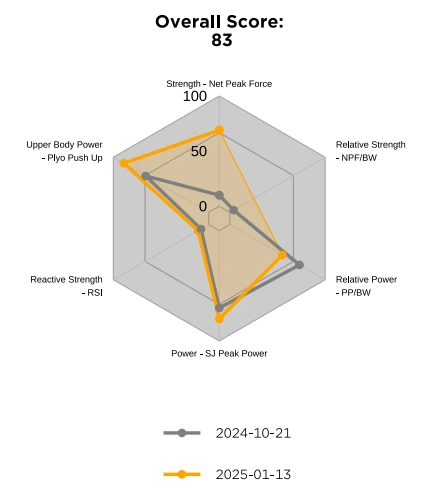

When Rogers returned to Driveline’s Arizona facility in early January a motion capture was planned. But our staff also wanted to re-test his strength to measure progress.

In two months, he had improved his strength score to that MLB average for a pitcher. That was incredibly encouraging.

Then he stepped on the indoor mound for his motion capture.

Gargas was curious to see what his fastball velocity would be, though it can be difficult to translate a lab-setting throw to a game equivalent as there is not the adrenaline of live competition, or 40,000 screaming fans.

Still, Rogers got up to 92.6 mph, a big improvement from his second half of the year numbers.

“I imagine when he came out to Arizona and threw the mocap, after his last outing of the season when he was struggling to throw 90s, to get on a mound (and throw 92.6 mph) … I think that probably gave him a ton of confidence going into spring training,” Gargas said. “Just all the work he was putting in was paying off.”

Their goal was for Rogers to average 93 mph with his four-seamer this season. He’s averaging 93.1 mph entering play Aug. 12.

And what was also encouraging from that second visit was not only a significant strength improvement, but the motion capture had identified a mechanical inefficiency. There was more juice to squeeze.

What was discovered in the analysis of Rogers’ throwing motion was a player who was trying to compensate for a loss of strength.

“What you’ll see guys do, if they are over-compensating, trying to find velocity, that will mess up sequences,” Gargas explained. “Guys try to apply intent too soon in the throw instead of letting the delivery, letting the energy travel up through the chain. As a result, that can impact some of the ball metrics. …

“One of things that did get flagged was his sequencing. Typically, what you see is the angular velocities, the sequence of when those are peaking, you normally see the pelvis peaking before the torso, and then the elbow, and the arm. In his case, there was a slight mistiming there where the torso was peaking before the pelvis.”

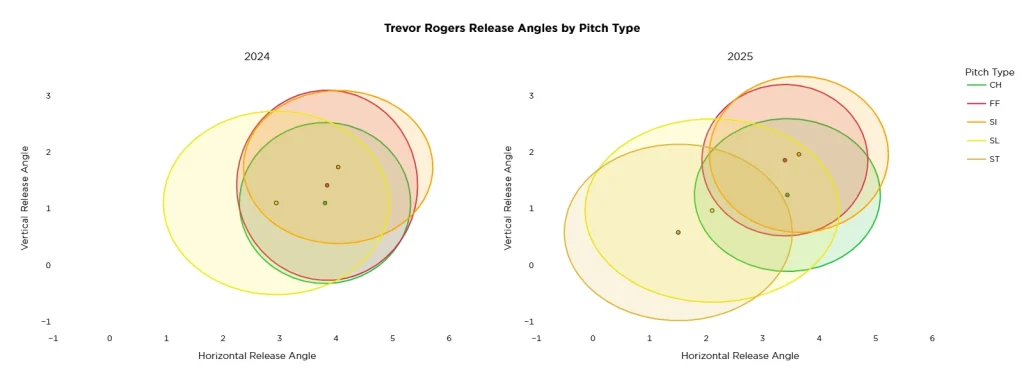

One related area where this showed up, Rogers believes, was his arm angle dropping to some of the lowest levels of his career last season. His arm angle has elevated from 21.8 degrees last August, to 23 degrees this season.

“Last year, I would try to produce velocity by spinning out and then my hand would dip under the ball, so I wasn’t staying truly behind the baseball,” Rogers said. “(The fastball) then tends to leak out over the plate, horizontally, rather than stay vertically. I think that was the biggest thing: my hand was dropping.”

Gargas said it’s also common for left-handed pitchers to have mechanical issues as they are often pigeon-holed into positions like first base and outfield. They don’t get to play the middle infield, like righties, and develop more athletic movement patterns.

“Those guys can struggle to rotate as a result of the positions they played their entire lives,” Gargas said.

To add variability into his offseason, to instill some more athleticism, Gargas created a regimen of drills – step backs and drop steps – to ingrain some more athletic movements. It’s a classic Driveline approach of implicit-learning tasks.

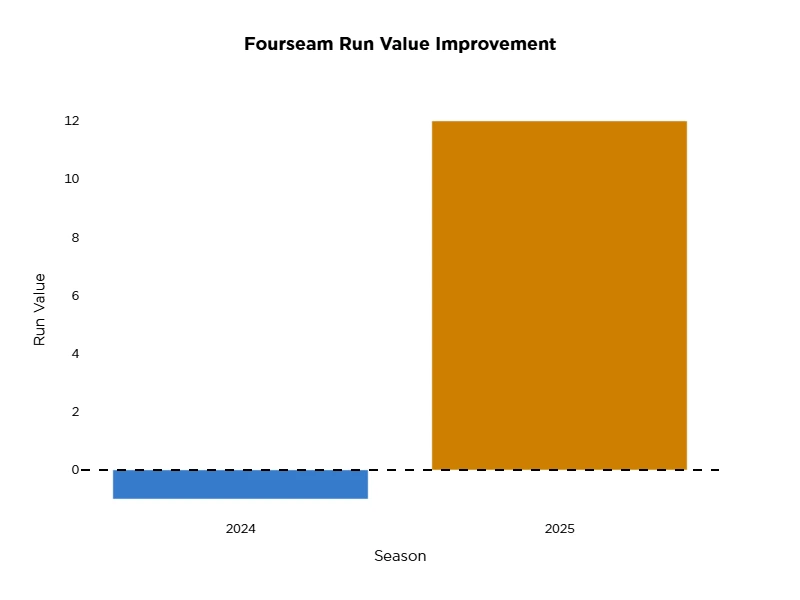

This season, his fastball is playing in the zone much more effectively.

Batters are hitting just .163 against his four-seamer this year (.250 last year). His whiff rate is up to 24% on the pitch and its run value (+12) is elite. It was a -1 run value last year.

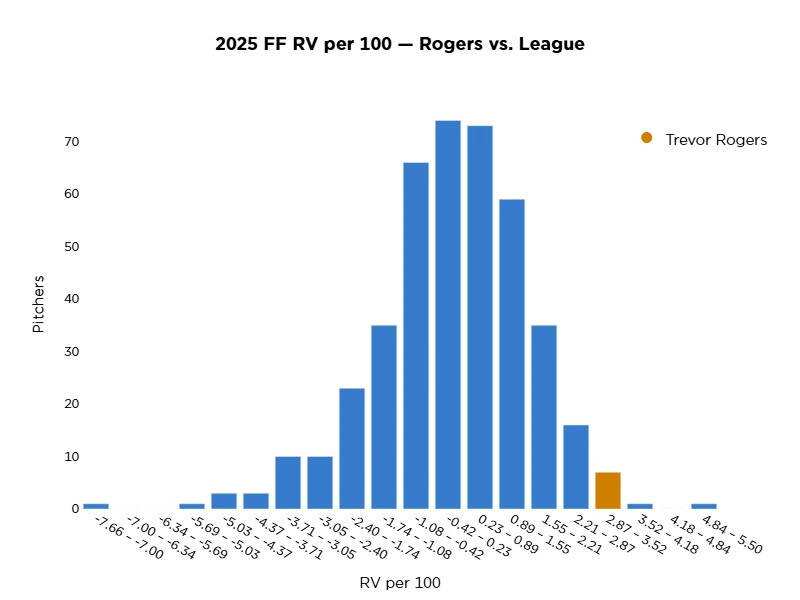

Rogers’ four-seamer ranks second in run value per 100 pitches (+3.4 runs/100 pitches), among all MLB pitchers to throw at least 100 four-seam fastballs, according to Baseball Savant.

Rogers also benefited from something else new at Driveline: The Mix+ and Match+ scores, created by Driveline’s Jack Lambert.

Match+ compares how similar pitches are coming out of a pitcher’s hand. The higher the score, the more the pitches mirror each other, and create swing-and-miss.

Mix+ evaluates how distinct the pitches are out of hand. These are pitch pairings designed to surprise hitters. A high Mix+ should result in more takes.

Pitchers, ideally, have both traits in their arsenal to complicate swing decisions and generate whiffs.

In looking over Rogers’ data, Lambert noticed that much of Rogers’ arsenal had excellent Match+ scores but poor Mix+ scores.

Wrote Lambert to Gargas when discussing Rogers’ arsenal: “The gyro-y slider he has has decent Mix+ since everything else is pretty armside-y. But if he wanted to fully leverage the ‘shock factor,’ or resetting a hitter’s gaze, he needs a bigger breaking ball shape.”

During his second visit to Driveline, he visited the pitch design lab.

“I was having a tough time figuring out a sweeper,” Rogers said. “It wasn’t clicking. It wasn’t doing what I wanted it to. They gave me different (grips). Went on the Edgertronic. Slowed it down. Finally got one. They said, ‘Whatever you feel there, keep doing it.’ There was some hit and miss with the reps, but I finally got it this year.”

Said Gargas: “He had spiked a decent amount of them but everything else was there. It was the classic Driveline ‘Oh, the shape of the pitch is there, can you get comfortable with the grip?’ He figured out how to set the sights necessary to land it.’’

Last season, Rogers had a breaking ball with a -10 run value. This year it’s above average.

Getting stronger, developing more efficient mechanics, and adding a new pitch were all key to Rogers’ turnaround. A classic Driveline experience – albeit with some new tools. But there was one more hidden aspect of his turnaround story.

Throughout his offseason, one key piece of tech that was always wrapped around his left arm: a Pulse sleeve.

For the first time in his playing career, just about every throw he made was tracked, its stress measured.

Prior to this, like so many pitchers, he was just guessing about what a recovery day should be, about what high intent meant, and how often he should be throwing with max intent.

“What I thought was a light day, I’d go into the app, and it was a heavy day,” Rogers explained.

Many first-time Pulse users do not realize they are doing too much between high-intent days or game performances.

“They then think about all the times after a start, or days they intended on throwing lightly,” Gargas said. “Wearing a Pulse for the first time, and seeing the numbers, it will often show you that you are not that far from your high-intensity days. It’s supposed to be 50% (intensity), and workload is supposed to be significantly lower, but you are making a ton of throws, and the intensity is way too high. Sometimes it just acts as a really good governor for guys who are suddenly aware. It’s just eye-opening early on. ‘Holy shit, all this time….’

“I think a lot of the big leaguers who train with us – and it’s never out of a bad place – but they end up doing too much. They had a rough outing the night before. Nobody wants to figure it out more than them that next day. They then realize ‘I never gave myself a chance to recover.'”

And like so many pitchers, Rogers did not realize that Driveline cares a great deal about injury prevention. It’s a key area of focus in research and development.

“I used Pulse the whole offseason. That’s when it was like ‘They care about keeping guys healthy,’” Rogers said.

Rogers was doing too much at his low point. So, last offseason he took his foot off the gas when he needed to, while also getting stronger, expanding his arsenal, and learning to better sequence his delivery. It’s a classic new-era improvement story.

It made Rogers valuable enough that the out-of-contention Orioles did not move him at this year’s deadline. He’s gone from being viewed as a regrettable acquisition to a critical pitcher the Orioles plan to build around. Perhaps the Orioles didn’t lose at last year’s deadline after all.

Comment section