Caught Looking: BFR, Shoulder ROM, and Hand-Eye Coordination

Here are three studies the R&D Department at Driveline read this month:

Comparison of blood flow restriction devices and their effect on quadriceps muscle activation

Blood flow restriction (BFR) is a common tool for rehab or strength and conditioning programs, and can be done using a few different methods. I’ve seen people use anything from a VooDoo floss band, to light elastic bands, to velcro straps, all the way to more capable BFR machines with custom pressure.

Bordessa et al. at San Diego State University used a couple different BFR methods to see how each of them affect muscle activation, pain, and perceived exertion in the quadricep muscles. The authors had 34 participants do knee extensions with two different types of BFR at 30% of their one rep maximum and without BFR at 80% of their one rep maximum. The two types of BFR were regulated and standardized—regulated maintains the same pressure on the muscle by adjusting strap size throughout the exercise, whereas standardized just keeps the same strap size the whole time. They found that:

- Muscle activation was higher in the heavy load, non-BFR condition than both BFR conditions

- Pain was higher in the regulated BFR condition than in the standardized BFR condition and the non-BFR condition

- Perceived exertion was higher in the regulated BFR condition than the standardized BFR condition and the non-BFR condition

More than anything, these results highlight how BFR may not be a replacement for heavy load. Muscle activation data using EMG is tough to interpret, and we don’t necessarily know if higher or lower muscle activation is better, but the difference in muscle activation between BFR with a light load and non-BFR with a heavy load tells us they are not accomplishing the same thing. That is also despite the subjective measures of pain and perceived exertion during the exercise being higher with one of the BFR conditions.

Comparison of the Effects of Static-Stretching and Tubing Exercises on Acute Shoulder Range of Motion in Collegiate Baseball Players

Deficient internal rotation of the throwing shoulder (Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit; GIRD) is a well-documented effect that sometimes arises in overhead throwing populations. GIRD is often accompanied by an increase in throwing shoulder external rotation, causing the total range of motion of shoulder rotation to remain close to the same. As long as the gain in external rotation closely matches the loss of maximum internal rotation (so that the athlete is not losing total shoulder range of motion), there is minimal cause for concern.

One of the approaches to minimize the amount of altered shoulder range of motion is the use of stretching and warm-up exercises. Warm-up routines are plentiful, and they usually include either active/dynamic movements, static stretching or a combination of the two. Most of the warm-up exercises we do at Driveline involve dynamic movements using banded or weighted resistance as opposed to static stretching.

Bush et al. at Ohio Wesleyan University looked into the effects of traditional static stretches and traditional band exercises (such as Jaegers J-Bands) on the passive range of motion of the dominant shoulder. Twenty five collegiate baseball players with GIRD participated in the study. There were six static stretches used for the static stretching condition and six band exercises using the bands:

Static Stretching Exercises:

- Two shoulder extension/horizontal abduction stretches

- Overhead shoulder flexion stretch

- Across the body shoulder adduction stretch

- Behind the head shoulder stretch

- shoulder internal rotation stretch

Band Exercises:

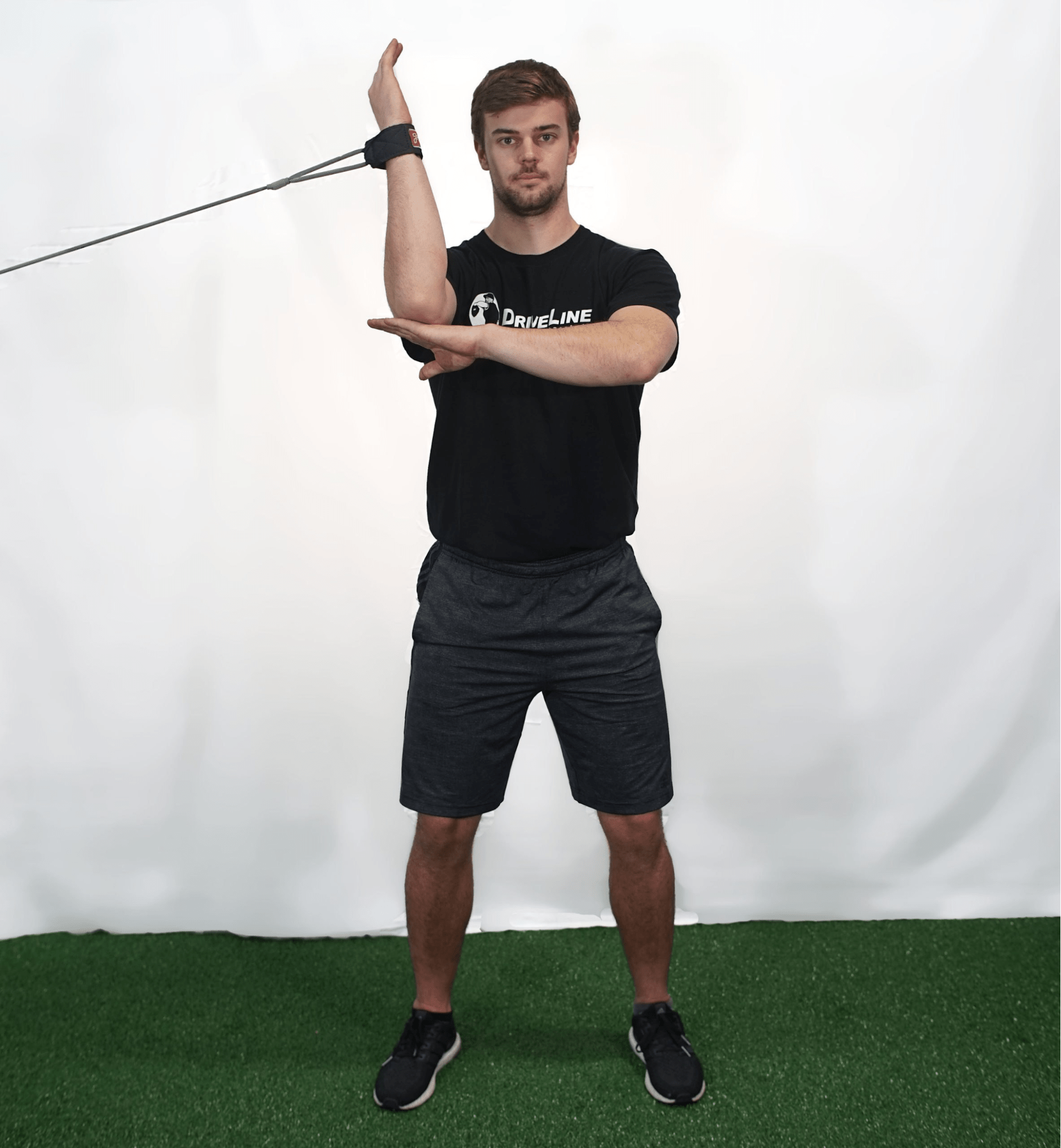

- 90/90 shoulder external rotation

- Shoulder flexion

- Shoulder extension

- Acceleration phase of the throw

- Deceleration phase of the throw

- Rows

The authors found that both types of warm ups improve internal rotation, external rotation, and total shoulder rotation range of motion when compared to pre-warm up. However, neither method improved shoulder internal rotation enough to declassify the subjects from having GIRD. The only difference between the two interventions was that static stretching elicited a greater increase in internal rotation from pre-to-post warmup than band exercises did, although the authors mentioned that the difference was not practically significant.

One main limitation with this study as a comparison of warm-up techniques is that passive range of motion doesn’t tell the whole story about how prepared a pitcher is to train or compete. There are other things that need to be considered to evaluate a warm up technique including: muscle temperature, muscle activation and nervous aspects of preparation, and other tissue properties of the muscles and other skeletal tissue. It is possible that two athletes can gain the same amount of range of motion but one of the athletes is more ready to throw than the other.

That being said, this is an interesting look at a comparison of two different warm up exercise classifications. Both of which could potentially be instrumental in managing range of motion alterations.

Visuomotor predictors of batting performance in baseball players

Hand-eye coordination is often mentioned when referring to the skills required to be good at baseball. As it turns out, this is not a easy thing to measure and prove, but Chen et al. at the University of Hong Kong attempted to do so with a visual tracking task and a simple motor task with a joystick.

Forty-four baseball players on the Hong Kong National Baseball team and 47 non-baseball athletes participated in three tasks. The visual tracking task was to simply follow a moving object on a screen while the gaze position of the participants was measured to determine visual tracking accuracy. The manual control task was similar, but progressed: that the participant used a joystick to keep the moving object as close to the center of the screen as possible, basically by compensating for the computer-led movement of the object.

Batting performance was evaluated using a mix of pitch types from a pitching machine and determining a ‘hit rate’ which was the total number of swings that led to hits out of the 30 swings taken per pitch.

The authors found that baseball players had better visual tracking performance and better manual control performance based on latency (lag) of movement, error in tracking, and the rate at which their eyes needed to catch up with a saccade (fast eye movement in which information gets lost), among others. Among the baseball players, however, there was not a difference of these capabilities based on experience.

The results of this study will likely won’t be applied to a player development program. However, it potentially highlights one of the primary components that baseball players (and maybe other athletes) develop throughout their playing careers. One of the most interesting things to me is that the lack of significant effect of playing experience on the coordination measures among the baseball populations shows how small of a difference there might be differentiating elite athletes from the less-skilled.

Comment section