How Proper Breathing Can Boost Athletic Performance

The importance of breathing has gained traction over the last several years as it pertains to the health and performance of not just baseball players—but all athletes. It’s safe to say that a large percentage of the baseball world has done some type of breathing drill during their career, whether incorporated into a warm-up, workout, or rehabilitation protocol.

While some players may understand why they were prescribed the drills, the full benefits of breathwork are largely unknown to the playing population. The goal of this article is to demonstrate the wide array of advantages breathwork can have for an athlete and to discuss ways to incorporate them into your routine.

How Can Breathing Help Me?

There are many ways that breathing can have a positive impact on an athlete’s health and performance—too many, honestly, to cover in this article alone. However, some of the more important effects include:

- Musculoskeletal effects, including improved mobility and stability

- Improved neurological effects, including heart rate variability and recovery

Disclaimer — Breathing is not going to be an easy fix for your performance needs if you have other, lower hanging fruit. If you weigh 150 pounds, focusing on your breathing technique isn’t going to allow you to hit the ball over the fence. If you’re drinking a 6-pack a night, you’re not going to recover from intense workouts better because your diaphragm is working right.

How Can This Impact My Mobility?

Generally, when I prescribe breathing exercises for an athlete, my primary goal is to affect a musculoskeletal change, whether that be improved mobility in an area or better trunk stability. There are several mechanisms by which this can occur. Let’s first look into what happens at the spine and rib cage.

The Spine and Rib Cage

Our primary muscle of inspiration is the diaphragm, a muscle that attaches to the bottom six ribs, the sternum, and the top three lumbar vertebrae. On average, we take over 20,000 breaths a day. In an ideal world, when we inhale, the diaphragm descends and flattens out, and the ventral cavity (rib cage/thoracic spine, abdominal cavity, and pelvis) expands in all directions. As we exhale, the diaphragm ascends and takes on a dome-like shape, and the ventral cavity compresses (If you would like a visual of this, here is a good example).

Throughout life, we can develop compensatory strategies that essentially reduce the amount of movement the diaphragm and rib cage go through during a breath cycle. The ventral cavity can stay compressed when it needs to expand and vice versa. When this happens, mobility can be reduced in various areas of the spine and rib cage. In these instances, an athlete can do all the thoracic mobility work they want, but will either:

- Not gain mobility since air needs to be able to move throughout the thorax for motion to occur, or;

- Borrow motion from another part of the body and potentially create a hypermobility issue

While this may appear to be a good demonstration of whole-spine flexibility, most of her motion is coming from her lumbar spine.

Restoration of proper mechanics of the diaphragm and thorax can frequently allow an athlete to make the mobility gains they are seeking, or at the very least, provide an opportunity for their mobility exercises to be more effective. This effect can also play a role throughout the hips.

During the breath cycle, the thorax’s inability to have a full range of motion also impacts the pelvis. Very often, this will cause the pelvis to be oriented anteriorly (the notorious anterior pelvic tilt!). While this orientation is not bad as your standard healthcare provider may make it out to be, it still can be an underlying cause of decreased hip mobility. With the pelvis tilted forward, the area where it meets the femur to create the hip joint also changes position. However, since your legs are often connected to the ground, the femur stays in a relatively constant position.

This moves the hip joint closer towards an end-range of motion, which reduces the amount of motion it is capable of to certain ranges. The analogy that I’ve used (credit to either Mike Cantrell or James Anderson) is that your hip is an elevator that wants to go up ten stories in a ten-story building—but you are already on floor seven. Again, if we can restore proper diaphragm and thorax movement capabilities, this can allow the pelvis to move into positions where more hip range of motion becomes possible (i.e. bring the body back down to floor zero).

I’m Already Mobile, I Just Need Better Core Strength

In addition to better spine mobility, improving breathing mechanics can improve stability throughout the lumbar spine and pelvis as well. There are a few thoughts as to how this can happen. Primarily, however, let’s take a look at how breathing can have an impact on posture.

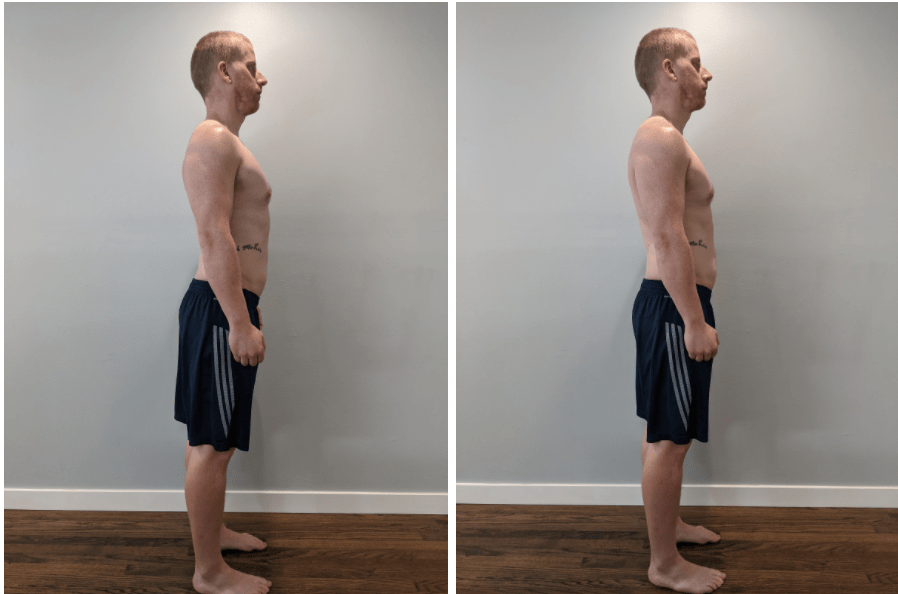

The picture on the left shows a person who is likely in a compressed posterior rib cage, diaphragm descended, pelvis anterior oriented state. From this position, many of the muscles that attach to the spine and pelvis, namely obliques and transverse abdominis, are going to be in a more eccentric, or lengthened state.

These muscles, along with others, provide a significant amount of control to the pelvis, rib cage, and lumbar spine. In this lengthened position, they are at a mechanical disadvantage in producing force and providing support to the structures they attach to. While the goal is not to “change” someone’s posture and make them more like the picture on the right, restoring breathing mechanics can allow those muscles to improve tension to better support the ribs, pelvis, and lumbar spine.

I’m in Great Shape. I Crush Myself in the Gym All the Time

Now that we’ve discussed the musculoskeletal effects of improving breathing mechanics, let’s take a look into what it can do for an athlete from a systemic perspective. It is well known that there are fluctuations in the autonomic nervous system that correspond to athletic activities. Our normal resting state is driven by the parasympathetic nervous system, where we are more relaxed, and our normal body systems, such as digestion, are able to function.

On the other end of the spectrum, during competition we are more driven by our sympathetic nervous system—our heart rate increases, blood rushes to our muscles, and we get into more of a “fight or flight” state. Being in a sympathetic state in competition is a good thing as it can enhance performance. However, being in that state for too long, too often, or being unable to come out of it can become problematic, as it is more taxing on the body and can hinder its ability to recover from competition.

This is where heart rate variability (HRV) comes into play. In a nutshell, HRV is how well our heart is able to handle fluctuations in its rate and, therefore, also handle stress. Athletes with low HRV will become more taxed by being in a sympathetic state, and potentially have difficulty returning to a parasympathetic state. Athletes with a high level of HRV will be able to handle that competitive state better and will be able to recover from hard competition or training more readily than someone with low HRV.

There are many ways to improve HRV in an athlete, but one of the easiest is to improve the athlete’s breathing capabilities. The autonomic nervous system and HRV are heavily regulated by the vagus nerve. Studies have shown that performing slow nasal breathing (around 6 breaths/minute) can improve vagus nerve activity, which in turn improves parasympathetic drive and heart rate variability.

To Belly-Breathe or not to Belly-Breathe

If you scour the internet for breathing techniques, you will find differing thoughts and ideologies as to the “correct” way to breathe. Mainly, there is debate on whether a person should fill the chest with air or focus on “belly-breathing”. I find myself falling into the camp of focusing more on getting air into the upper rib cage, with the following caveats:

- The athlete shouldn’t overuse their neck musculature to inflate their upper rib cage

- The athlete shouldn’t perform a hard “brace” with the front of their abs, thinking they are creating ab tension

My opinion is that a properly performed respiratory cycle with the intention of improving movement capabilities should be performed with a complete, full exhale. This will naturally create tension throughout the obliques and transverse abdominis that should be maintained to essentially give the diaphragm a better ability to drive airflow into the upper rib cage, which will allow for improved thoracic mobility. The video below should provide a good demonstration of this.

It has been my experience that a focus on belly breathing does not adequately allow the upper rib cage to expand, and, additionally, makes it more difficult to keep the abdominal musculature in a position to best control the pelvis, spine, and ribcage. I also hold the opinion that air should primarily go where your lungs are, which the last I checked, is not your stomach.

Lower ribcage and trunk expansion with upper ribcage compression. Potentially a belly-breathing effect.

With that said, there are plenty of providers and coaches that have had success coaching a belly-breathing technique, and at the end of the day I think the MOST important thing that needs to be taught is that breathing should be slow and inhalation should occur through the nose.

Generally, I have my athletes perform 1-2 exercises in certain positions as part of their warm-up to achieve whatever movement effect I am trying to create. I then have them do one of the exercises as a cool down, primarily for the purpose of getting them out of the sympathetic state that training can drive, and bring them into recovery mode.

I’m Not Blowing Into a Balloon

One thing that has left a bad taste in the mouths of those who’ve tried these kinds of breathing exercises has been the use of balloons. Mostly used under the Postural Restoration Institute umbrella, a balloon can be used to provide a bit of resistance for the obliques and transverse abdominis to work against, eliciting a better stabilization effect on those muscles.

However, it has been my experience that for the majority of athletes a focus on a full exhale, followed by a 4-5 second pause, and then maintaining tension during the inhale should be enough to get the effect you are going for. So you can hold off on the balloons.

By this point, the importance of incorporating some type of breathing drill into your routine should be more apparent. A significant degree of experience or knowledge is not required to incorporate exercise that will yield results. Taking a short period of time to utilize this technique can have great results on an athlete’s health and performance.

By Terry Phillips DPT

Comment section