What is the Value of a Prospect? An Updated Methodology

This off-season and spring training have seen a major upheaval in the number and type of coach that is being hired into the professional ranks, while the use of technology throughout all levels of professional baseball has increased drastically.

This new level of investment demonstrates clearly that teams are valuing player development more highly than in the past. But, even with millions of dollars pouring into new technology, personnel and methods, a question remains:

Are teams investing enough?

Over the next few months, we’re sharing several articles that look at Major League player development from a different perspective relative to what you typically see on this blog. We are going to look at the business case of developing baseball players to try and determine an appropriate level of investment by a team.

Our goal is to understand if organizations fall short in leveraging their resources to optimize a player’s career trajectory. Ultimately, we’ll attempt to evaluate how much suboptimal habits cost organizations in the long run.

Before we can accomplish that, we need to address how much a given prospect is worth to an MLB team. By performing an analysis to generate our own valuations, we can quantify the net value of any persistent inefficiencies that may exist within player development today.

Our series on The Business Case for Development begins with this feature and will have several parts:

- What is the Value of a Prospect? An Updated Methodology

- The Value in Optimizing Player Development From the Lens of Generating Velocity

- Programming Risk and the Associated Outcomes of Lower Level Prospects

- Homegrown WAR: How Much Production from Homegrown Prospects is Needed to Compete?

- Traded In vs. Traded Out: Comparing Player Development Departments Based on the Performance of Team Switchers

- Drafting High Ceiling Prospects: Getting Peak Value In Acquiring and Developing Talent

- The Rise of Replacement Level and the Early Peaking Aging Curve: Is it More Difficult To Acquire Talent in the Open Market?

- Realizing Returns on Player Development: Do Additional Coordinators and Affiliates Make the Difference?

Valuing Prospects: Full of Assumptions

Valuing prospects on a per-dollar basis is not a new concept. Creagh & DiMiceli, Zimmerman, and Edwards have previously laid out extensive blueprints on how to derive prospect valuations. However, since there is no so-called right way to calculate these figures, each piece has relied on its own set of assumptions, which have created discrepancies in the respective values reported.

Some arbitrary choices, such as choosing an appropriate estimate of $/WAR and a discount rate, are simply unavoidable given the nature of task. However, other assumptions are shortcuts of more granular analysis, because going through historical WAR and salary values on a yearly basis is tedious and potentially unreliable if not done carefully.

We have never shied away from the tedious.

Our prospect-valuation model minimizes these shortcuts to improve confidence that our results accurately depict how much a prospect is truly worth.

As an aside, the “true worth” of a prospect is best described in layman’s terms as what a team should pay to acquire that player given the price of acquiring production in the open market.

Calculating $/WAR

The first step in this process is to calculate a $/WAR figure that best represents the current standing of the market. Any aggressive or conservative estimate of $/WAR can skew prospect valuations by a relatively large margin, so it’s important to get this right.

Fortunately, Matt Swartz has provided a sound method on how to derive a reasonable proxy of $/WAR within a given season. We replicated his work and gathered the names and salaries of every player with at least six years of service time in a given season since 2010. We then paired these player seasons together with each player’s respective Fangraphs WAR (fWAR) output and summed both veteran production and salaries on a per-year basis. To account for situations in which a veteran cost a team a draft pick, we added the NPV (Net Present Value) of the attached pick to said player’s first-year salary on his new contract, because this is when teams forfeiting the pick incur that cost.

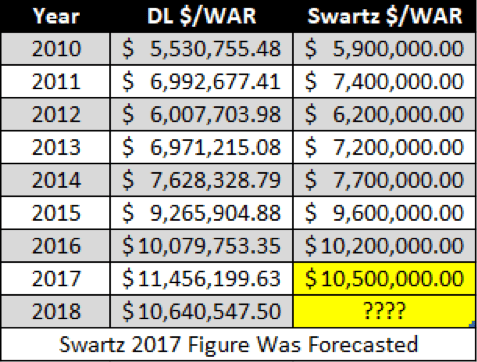

By dividing the sum of veteran salaries by the sum of veteran fWAR, we obtain relatively conservative market estimates of how much teams spent to acquire a win in the open market in a given season (with the caveat that players who signed extensions were included in our sample). We’ve compared our estimates (DL $/WAR) to Swartz’s (Swartz $/WAR) from years 2010 to 2016 to validate our 2017 and 2018 figures, shown in the table below.

Projecting 2019 $/WAR

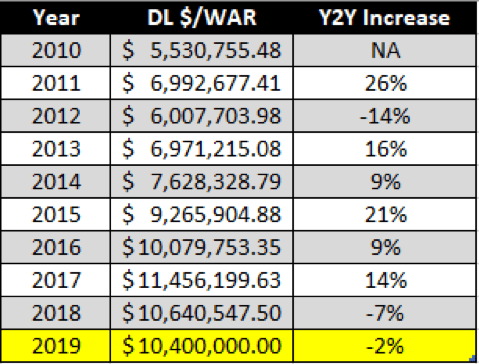

While reassuring that our figures are consistent with ones published by Swartz, the uncertainty that surrounds the influence of the newest CBA on teams’ spending habits makes it difficult to use these historical estimates to forecast an accurate $/WAR figure for 2019. As shown above, since MLB instituted stricter spending limits and penalties on payroll expenditure in the 2017-18 offseason, the market has been in a deflationary period.

To workaround these limitations, we turned to the Steamer Projection System and gathered projected WAR and salary estimates for all veterans during the 2019 season. Given that prior research has found projection systems are overly optimistic in their forecasts of veteran production by roughly 15% and that aging curve peaks have been trending younger, we also performed this analysis on 2018 data to get a sense of how biased these figures are in the present day.

In first looking at 2018 projected $/WAR, we found that our new estimate came in at ~71% of its actual value, falling from $10.64M to $7.6M. For 2019, projected $/WAR came in a hair under $8M, which we now know is only ~70-85% of what the actual figure will be for the season. To correct for this, we multiplied $8M by 30% to obtain a $/WAR estimate of $10.4M for the upcoming 2019 season.

This $/WAR estimate ends up being significantly higher than the $8.5M and $9M suggested by Creagh & DiMiceli and Edwards to calculate their respective prospect valuation figures. However, our $/WAR estimate is derived from actual market data rather than intuition. To justify player valuations in the $8-9M range, $/WAR would have to drop by over 21% in just a two-year period. That seems unlikely.

Furthermore, even if $/WAR on the open market hypothetically fell to levels below $10M, we believe that there are two reasons why a simple estimate of $/WAR would actually undersell the value that homegrown production provides an organization.

The Merits of Homegrown Players Vs. Free Agents

First, there is little potential for sunk costs with homegrown players because their salaries are not guaranteed beyond one season at a time.

For example, in acquiring Jonathan Schoop last year at the trade deadline, the Brewers obtained a potential buy-low bounceback performer who could have simply been non-tendered at the end of the season (at no cost to the organization) if an uptick in production did not occur. Hypothetically, had Schoop returned to his 2017 production levels, the Brewers would have likely exercised the right to retain his services for the 2019 season and extracted additional surplus value beyond the 2018 season. Thus, by acquiring Schoop, the Brewers obtained loads of upside at relatively no risk, which surely drove up the price point they had to pay the Orioles in order to receive his services.

Homegrown players also possess minor league options for 3 years, which can be used for developmental purposes (see Alex Gordon’s 2009-2010-2011 seasons) and additional roster flexibility (see the Dodgers and A’s 2018 starting rotation) that provide teams with added value that open market players cannot offer.

As a result, teams should be willing to pay more in terms of $/WAR for these players given that they possess team-friendly volatility that includes hypothetical team options after every season. As a result, their distribution of outcomes generally contain much higher upside than a typical free agent does, and the risk is mitigated by the fact that future salaries are reliant on production itself.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that a two-WAR season from a homegrown player is worth more to a team than a two-WAR season from one acquired through free agency. However, if we hold salaries equal, it does mean that teams are relatively protected over multiple years from a worst-case-scenario outcome in the case of homegrown players. This creates value for teams (either through trade or over multiple years) that should not be ignored.

Second, since payroll expenditure is now a constraint on acquiring wins in the open market for several large-market teams (who are traditionally on the steep slope of the win curve), players who generate surplus production at relatively low cost can also give teams the flexibility to spend elsewhere on their roster—which in itself has value.

For example, a team within $20M of the “cap” (err…tax threshold) would not be able to extract full surplus value if they were offered a trade for a five-WAR player at $25M per year, given the tax and additional penalties they’d be subjected to. However, this same team would be able to extract maximum surplus value from a three-WAR at $5M per year player if offered via a trade and thus would likely be willing to pay more to acquire that asset (despite each player having similar surplus values).

As a result, players who are productive at lower salaries (typically homegrown players) are likely more valuable to a given team than a simple $/WAR estimate gives them credit for. Thus, if we construct an approach to valuing prospects that uses $/WAR and select a figure below market rate, we will likely underestimate our prospect valuations by fairly significant margin.

Determining a Discount Rate

As described earlier, to calculate prospect valuations we also need to select an appropriate discount rate that reasonably estimates how much a team would trade a win today for a win a number of years in the future. Getting this number to be fairly accurate is critical because prospects can take a while to develop and fulfill their six years of club control. Any mis-estimation of the market’s discount rate can compound on itself and skew our results by millions of dollars. (See Bonilla, Bobby.)

To pinpoint a discount rate, we again turn to the work of Matt Swartz, who has previously used the difference in $/WAR spent by teams on free agents with and without draft-pick compensation attached to them in order to find a discount rate that causes both FA groups to have equal expenditure. (For more info on his methods and why the rate is estimated to be relatively high, click here.) Historically, Swartz has found that the discount rate fluctuates at around 10%, but that the value is subject to a large amount of variance on a yearly basis for a variety of reasons.

Given the variability and limitations associated with estimating a discount rate, we decided to select the 9.3% figure provided in Swartz’s initial work on discounting future values in baseball. In using 9.3% instead of 10%, we select a figure that is more closely aligned with the discount rates chosen in prior prospect-valuation research. Furthermore, this figure was calculated when draft-pick compensation was easier to tease out and when $/WAR estimates were more likely to still be linear. (In a case where $/WAR was no longer linear, Swartz’s analysis would no longer be feasible given that only a specific subset of free agents are offered QO’s.)

How Much Are Prospects Worth? Methods to Calculate Prospect Surplus WAR by Rank

With a framework for deriving $/WAR and discount rate established, we can calculate prospect values.

To do this, we use Baseball America’s historical top 100 list, as they’re the most easily accessible resource of historical prospect rankings to build out our database.

We collected BA’s rankings from 1995 to 2009 and assigned each player with a coinciding WAR value (from Fangraphs), playing-time figure (from Fangraphs), and salary (from USA Today and Fangraphs) for each season that followed a year’s respective ranking.

Building this database answers questions like, “How much WAR did Alex Rodriguez produce in 1998 at his salary just three years after ranking atop Baseball America’s Top 100 in 1995.”

This structure allows us to work with more precise measures of analysis relative to previous work on prospect valuations, which finds a prospect’s total WAR accumulated over the first X number of years of his career and then relies on several assumptions to estimate how much money that prospect will earn through arbitration and how his value will be distributed over the first several years of his career.

The alternative methodology used by previous analysts is understandable since it avoids having to use historical estimates for $/WAR. However, there is always the risk that the assumptions used end up being misguided in practice.

The most glaring mistake we note is how previous estimates have tended to distribute the WAR and salaries earned by players over the first seven to nine years of their careers equally, regardless of whether they are the first or hundredth best prospect. Since top prospects are typically closer to the big leagues than those at the bottom of the list, any one-size-fits-all distribution assumption will inherently overvalue one tier of prospects at the expense of another when redistributing and then discounting WAR. Unless separate tiers of prospects are treated differently in terms of how surplus WAR is redistributed, you are giving a relative advantage to one group over the other.

For example, in Edwards’s most recent valuation work, the production within the first nine seasons of a player’s career WAR was gathered and redistributed two years into the future. By using nine years instead of seven, Edwards likely inflates the value of top prospects, who are more likely to produce larger amounts of cumulative WAR over longer periods of time and are closer to the big leagues. To counteract that, Edwards then pushes these inflated WAR values two years into the future, which deflates the relative value of top prospects given that they are more likely to have an ETA sooner than two years.

These issues compounds when you “smooth” prospect values by rank, as the “slope” of your line will either be too sensitive or not sensitive enough, helping or hurting top-tier prospects relative to the rest of their peers.

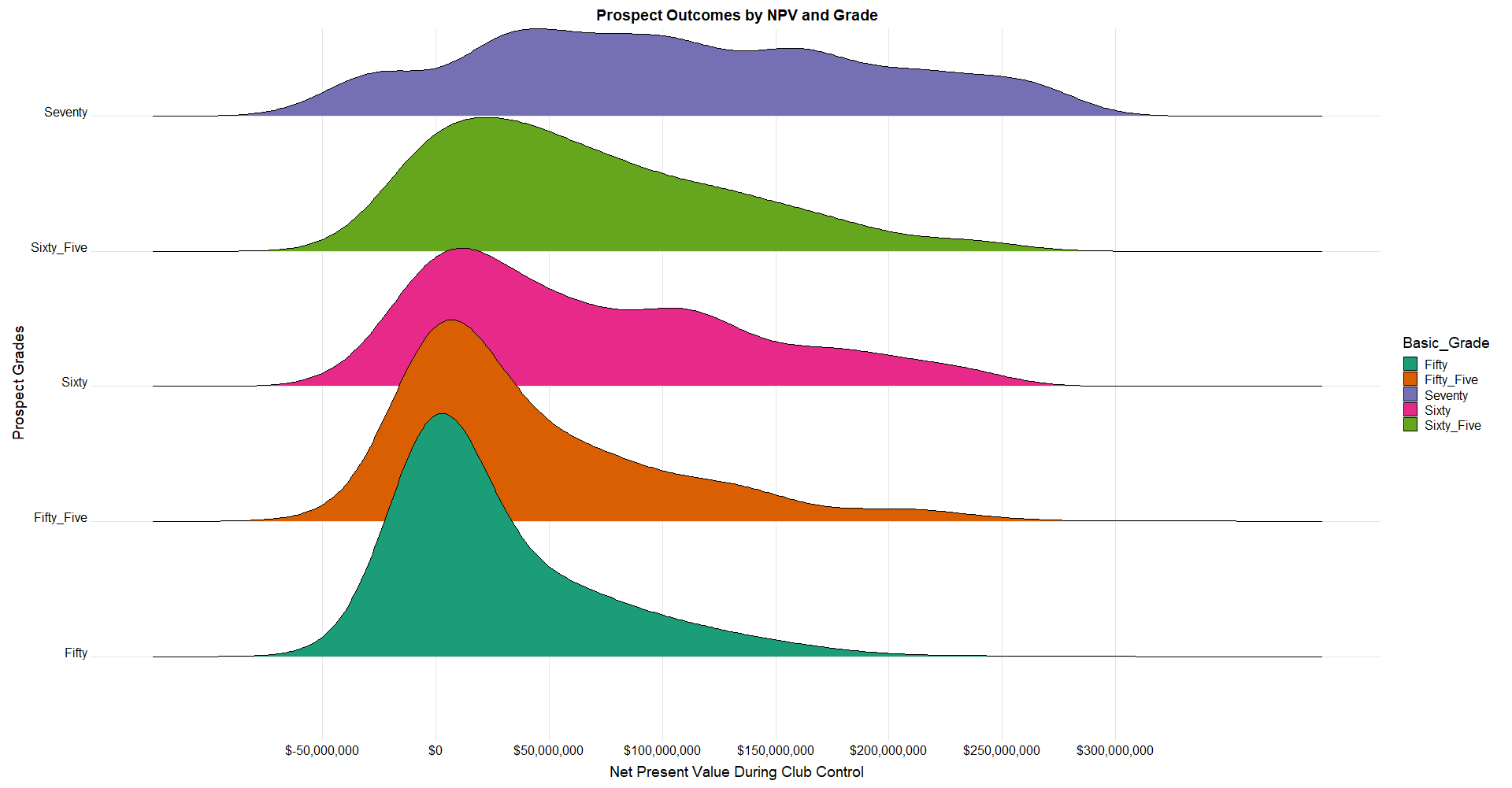

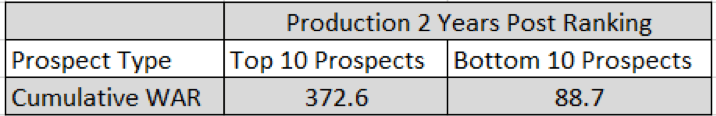

(This compares the production of Top 10 prospects vs. Bottom 10 prospects by WAR within 2 years after being ranked)

To avoid this pitfall, it’s better to rely on more precise measures of surplus WAR that use only actual production/wages and historical $/WAR to bring surplus wins back into present day context. (Historical estimates of $/WAR pre-2006 are simply calculated from how much WAR free agents usually produce in a given season [~30%] and how big their share is in terms of the overall salary of the league [~75%.])

Once we calculate the yearly surplus value of a top 100 player before he reaches six years service time, we discount those values by 9.3% raised to each year after the coinciding rankings come out. We then translate those values into present-day dollars and sum the yearly totals by player in order to find the total discounted surplus value per player during his years of club control.

Fitting Prospects Grades to Rankings

Equipped with these newly calculated NPV metrics by prospect ranking, we next turned to Fangraphs scouting board to convert the rankings of each individual player listed on BA’s Top 100 into prospect grades. This will allow us to compare prospects based on their actual projected value, rather than a ranking system that treats the 99th and 100th best prospects differently despite both of them having the same future value.

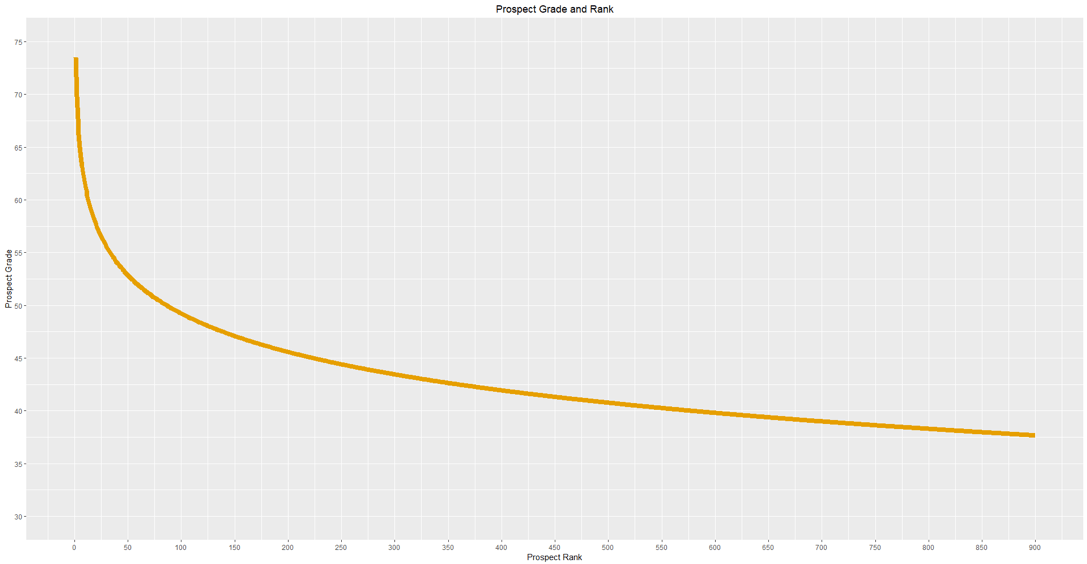

On Fangraphs “The Board,” three different sets of prospect lists sorted by both grade and ranking are available to run a simple regression to obtain predicted prospect grades based on prospect rank. With over 2,000 players graded and ranked within that time period, we generated an estimated prospect grade ranging from 35 to 70 for players ranking 900th or higher on a prospect leaderboard. The grade-to-ranking results are in line with what Edwards recently reported within his analysis and are provided below.

**Strikingly, if ~900 prospects across all 30 teams are graded 35 or higher, that means >75% of minor league baseball players have no expected production in the big leagues. Thus, being able to develop organizational depth into substantive value could help teams to realize large returns, something we will address in future blog posts.**

Results

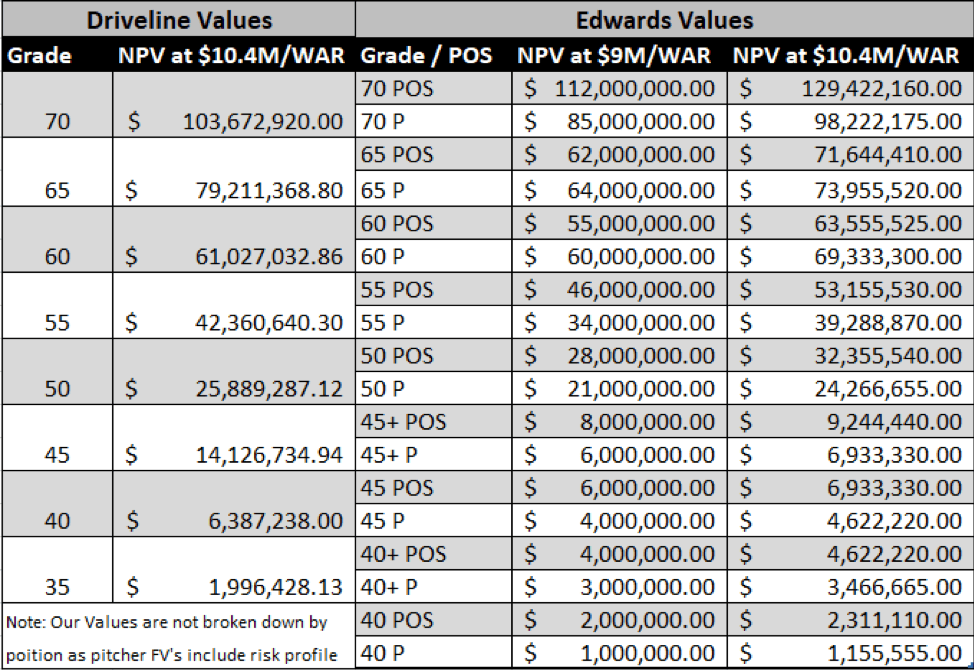

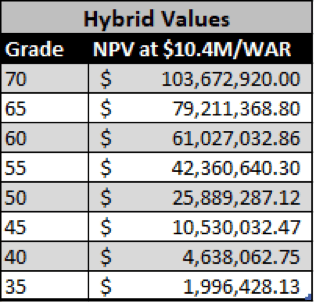

Now that we have surplus values and estimated prospect grades for each prospect listed in BA’s Top 100 from 1995 to 2009, we ran a model to smooth out our surplus values by prospect grade. Once we fit these results onto a year’s worth of prospects graded above a 35, we then binned the values by prospect grade and received the values below. For comparison purposes, we added Edwards’s estimates both at $9M/WAR (what is published on Fangraphs) and at $10.4M/WAR.

In comparing the numbers a bit more closely, we observe that figures from both models are fairly similar at the top half of the table and then diverge significantly for 45 grade prospects and below. Finding similar results between models for prospects graded 50 and above is validating and a testament to Edwards’s intuition and strong assumptions.

However, in most financial models of farm systems, the returns come from having a high hit rate among top prospects and getting value from players outside the top rankings, those ranked 45 and below. Having an accurate model for the top-end of the prospect world is good, but we need to ensure an accurate evaluation of non-elite prospects as well.

Entering the Trade Market, Validating Our Results

To test our model’s results for sub-45 prospects, we evaluated MLB trades to see if teams were exchanging wins for prospects at prices we would expect given our model’s valuations.

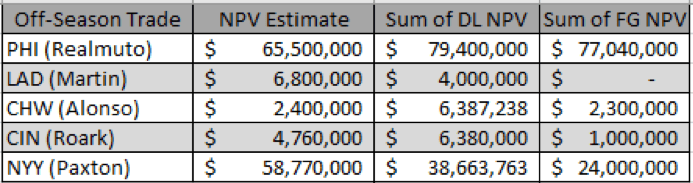

To avoid skewing our results by including shaky forecasts of players with more than two years of service time and more than two years on their current contract, we first looked at a handful of simple trades that occurred during this off-season. In the left-hand column you see our estimated value of NPV for the big leaguer acquired (based on a $10.4M/WAR estimate and Steamer predictions) alongside our estimates for value of prospects exchanged in the deal (Sum of DL NPV) and Edwards’s estimates for the value of prospects exchanged in the deal (bumped up to a $10.4M/WAR estimate).

**Note that Alfaro had five years of club control remaining and was most recently graded a 45. We simply multiplied his respective 45-grade value by .8 to obtain to obtain his NPV. Also, Realmuto’s Steamer projections do not include framing, which means his NPV is likely underestimated in the chart above.**

Given the small sample size and the relative noise surrounding how the market dictates player values, it’s tough to take much away from the table. Initially, it looks like our estimates might come in a little bit high on players such as Alonso and Roark while Edwards’s values seem to come in too low on Martin and Roark.

In general, these initial findings make sense, as the appropriate values for prospects ranked 45 and below seem to drop off precipitously and our model lacks prior information on the actual success of these said players to adjust for this. (The 100th ranked prospect is typically a 50.) It is therefore reasonable to believe that our model is just overly optimistic for 45-grade prospects.

On the flipside, Edwards uses some clever methods to project surplus value in prospects outside BA’s Top 100, but these methods fail to account for players who drop out of BA’s Top 100, still make the big leagues, and end up being productive. Thus, his numbers might slightly deflate the proportion of WAR that 45-grade prospects and lower might actually deserve.

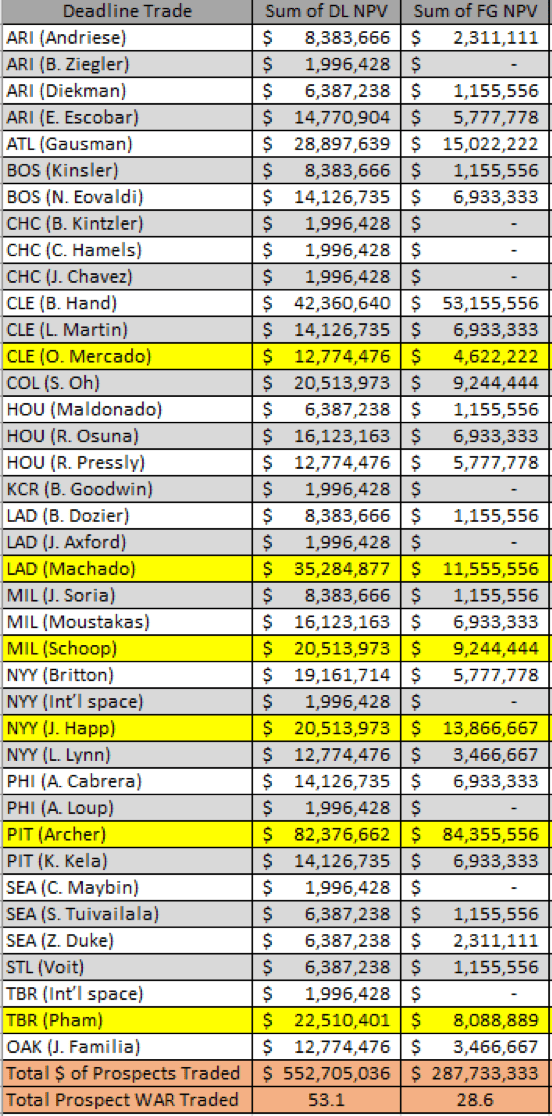

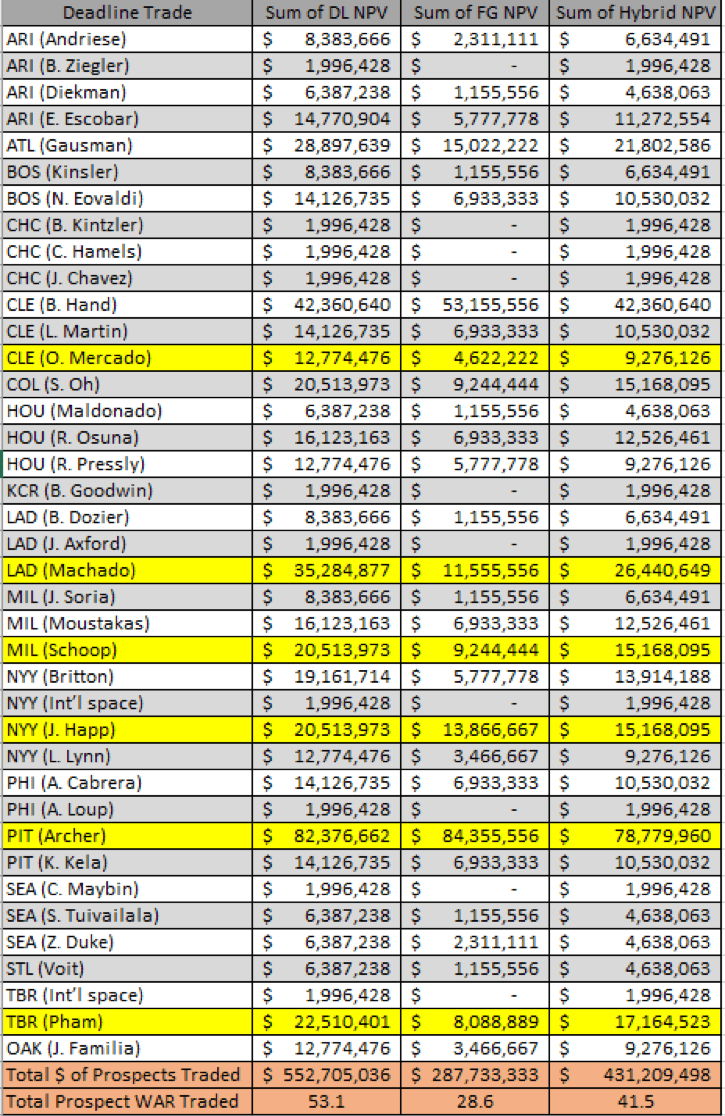

Regardless, to confirm this hypothesis we need more trades. So, we pulled the major transactions at the last trade deadline and performed a similar analysis to what was provided above. Rather than attempt to pinpoint a specific NPV value that a team acquired through MLB talent (likely impossible given the hyper-specific context in which each player was acquired), we instead decide to highlight the more interesting trades.

Initially, a $275M discrepancy may not look promising, but our models are diverging as expected. For example, our numbers seem to overshoot the players traded for Schoop, Happ, and Britton, whereas Edwards’s numbers seem to undershoot the likes of Machado, Pham, and the majority of relievers who had bundles of 40s and 35s packaged for them.

A Closer Look at Two Trades in Particular

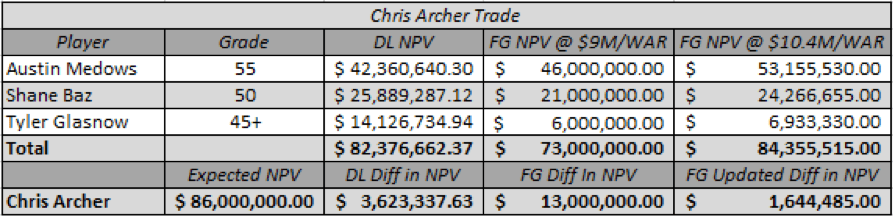

Two other trades worth mentioning are the Chris Archer deal, which Edwards highlighted within his main article as a validation of his figures, and the Oscar Mercado deal, which is a bit peculiar but provides unique insight into how teams value prospects themselves.

In the case of the Archer deal, both models provided almost identical values once we accounted for the necessary boost in $/WAR for Edwards’s figures. This gives us strong confidence that our higher-profile prospect valuations are both fairly accurate and consistent.

Exchanging Prospects for a Prospect

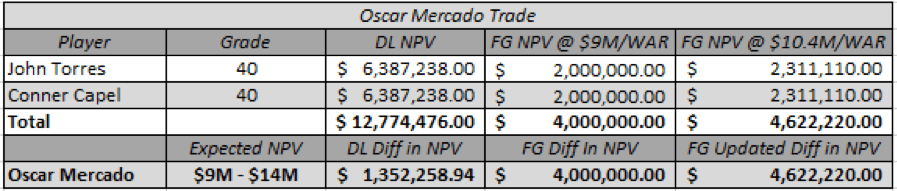

The Mercado deal is perhaps both models’ most telling test because we’re dealing with a rare prospect-for-prospect trade in extenuating circumstances.

It was seen as puzzling when announced, but with Mercado being Rule 5 eligible and already on the Cardinals 40-man when 40-man spots for outfielders in St. Louis were virtually all accounted for, it was likely that the Cardinals were forced to move Mercado in order to salvage any value out of the situation.

Given this context, we’d imagine that no team would be willing to pay full price for Mercado knowing very well that St. Louis has no leverage—they’re going to lose Mercado to the waiver wire regardless. However, we also know that almost every team who projects to have an opening on their 40-man in December should be interested in acquiring Mercado given the low price point. As a result, we’d expect interested teams to drive up the price so that STL would receive and accept an offer that comes in just below Mercado’s estimated surplus value.

To test this assumption using our model, we compare the net value of a 45-grade prospect at ~$14M in exchange for two 40-grade prospects valued at ~$6.4M each. In doing so, we find that the prospect package St. Louis received from Cleveland comes in about $1.35M below Mercado’s estimated surplus value, which is about what we’d expect given the context above.

Using Edwards’s model, we estimate that a 45+ position player prospect is worth about $9.2M and that a 40-grade position player is worth about $2.3M. When you do the math, Edwards’s model favors Cleveland’s side of the deal by ~$4.6M, likely too large of a discrepancy to accurately depict how both teams valued the players exchanged.

Meeting in the Middle

Given what the trade tables tell us, the best way to model how teams actually value prospects their lower-tier prospects is to hedge in between both models for prospects graded 45 and lower. By averaging our respective 40- and 45-grade values, we hopefully clean up our overly aggressive rankings on 45-grade prospects and boost Edwards’s underreporting of 40-grade prospects and lower.

In looking at the newly added column, which incorporates our combined prospect values, we see more palatable numbers across the board, with maybe one or two exceptions sprinkled in. In revisiting the Mercado trade with our new numbers, we end up ~$1.25M off the mark this time, which is reasonable and well within an estimated margin for error given the limitations of the data that we are working with.

With added confidence in these new figures, we present the newly adjusted prospect valuation numbers below.

Where to Go From Here

Looking ahead, these new prospect valuations will be the foundation for many of the articles we intend to write on player development.

With a better understanding of the value realized by organizations when prospects improve their status from one grade to the next, we gain insight into how much is at stake when a player’s career trajectory can rise or fall based on the environment and programming he is subjected to.

We’ll take this information to evaluate player development departments, analyze appropriate programming risk, and address suboptimal behavior exhibited by professional organizations as they look to gain the most value by enhancing player development. In the long run, we feel that this analysis will provide coaches, players, and fans with better insight into how much value teams are leaving on the table.

Written by Research Analyst Dan Aucoin

Comment section