Youth baseball is searching in the dark regarding workloads. What can be done to illuminate a path toward reducing injuries?

Everyone knows the problem: too many young arms are getting hurt.

Everyone knows too little is being done to address it.

But the injury scourge persists as youth baseball is generally searching in the dark for answers.

Even if a well-meaning parent or coach wants to be responsible, it is difficult to know what the throwing guidelines should be.

Deven Morgan, Driveline’s Director of Youth Baseball, presented on the youth pitching epidemic at the ABCA convention in Columbus, Ohio last month. Morgan is passionate about reducing the injury crisis and creating smarter guidelines and throwing programs.

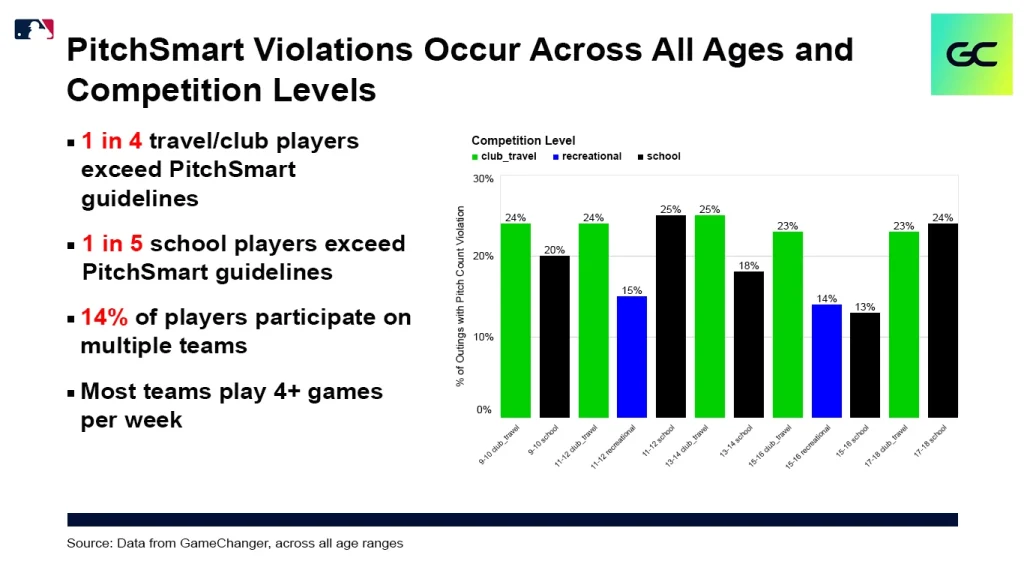

He shared with me how one in four pitchers on a travel team exceed Pitch Smart guidelines, and one in five players on junior and high school teams exceed the guidelines. That’s according to data from Game Changer across all age platforms.

Moreover, 14% of players play on multiple teams, and those players are generally the best athletes, meaning they are candidates to pitch for multiple teams. That can be problematic when those teams are simultaneously in season. Teams can play four or more games a week in season.

We know there are too many injuries, and we know why injuries happen, or at least what leads to a sizable portion of them: fatigue.

Fatigue leads to kinematic changes, which leads to kinetic changes, which leads to performance changes, which can lead to more kinematic changes, and the domino effect eventually leads to injury.

We know there’s been a major increase in injuries among youth pitchers. MLB’s injury report published last December documented how the share of Tommy John surgeries performed on high school and youth arms by the Andrews Institute is averaging about 50% of all procedures performed there since 2015.

“That’s a pretty shocking number and definitely indicates that we have some stuff to figure out,” Morgan said. “Because on no planet should that be happening,”

The culprit often cited is the emphasis on increasing throwing velocity and overworked young arms.

There’s no doubt that more energy and more force are needed to create more velocity. But the stuff and velocity benchmarks needed to compete at the college level or pro level are only increasing. There are great financial incentives for pitchers to reach those levels. It’s difficult to see how one would disincentive trying to improve skill level.

But what’s frustrating is we know overuse is a rampant problem, and that it leads to injury, and the baseball industry just is not doing enough about it.

And one big reason why not enough is being done is youth baseball is flying blind.

The industry needs more data.

Pitch Smart is a start, a noble effort. But it’s hardly perfect, starting with a lack of comprehensive reporting.

“You had some organizations were like, yeah, we’ll send that stuff out to our coaches, but we’re not going to actually deploy a system or track it,” Morgan said.

The recommendations are largely estimates, guesses, not backed by statistical rigor, because, again, the data does not exist.

Even at Driveline, our sample of youth athletes who have multiple years of training with PULSE – including Noah Coury, who we recently featured – is a small sample relative to the scale of youth baseball.

“We’ve got some kids, I just don’t know that we have enough,” Morgan said. “And if we don’t have that data, then nobody has it.”

That’s a big problem. It’s one Morgan is interested in helping solve, along with other potential partners, like MLB, with a Pitch Smart 2.0.

Like with anything, progress begins with measurement. For instance, if we want to gain or lose weight, we begin by stepping on a scale to monitor progress. We need more information to study.

And that’s where new systems combined with PULSE data can begin to reduce the injury plague.

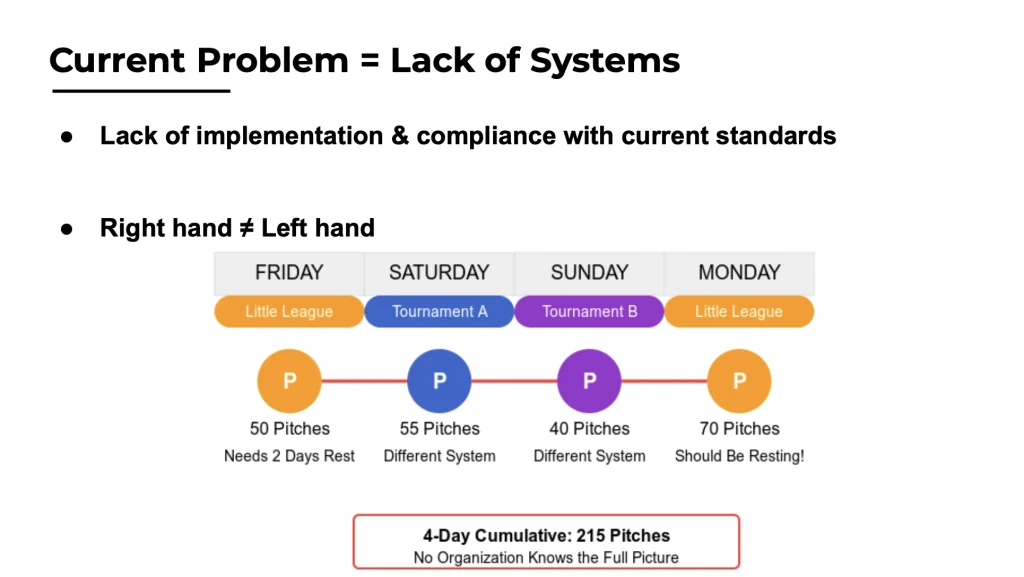

One big issue today is a lack of systems.

Let’s consider a hypothetical situation involving a youth pitcher who plays for both a Little League and travel team.

On a spring Friday, our little leaguer throws 50 pitches in a game. He should have followed that with two days’ rest, according to workload recommendations. Instead, he and his parents traveled to a weekend tournament and pitched back-to-back days, totaling 95 pitches on Saturday and Sunday. His travel coach was either unaware he had thrown Friday, or he was too interested in winning.

“Increasingly, there are coaches who may ascribe some amount of their sense of self to their youth baseball team’s competitive ability,” Morgan said. “And that’s a (expletive) nightmare.”

He returns home to play another little league game on Monday and throws another 70 pitches.

Over four days, our overworked little leaguer totaled 215 pitches in four days. That should never happen, but it happens routinely across the U.S. as no organization has the whole picture even if they want to comply with standards.

Even if this hypothetical travel coach was aware his player had pitched; he had no access to a database showing how much work he had done. Data does not do any good if it doesn’t have an accessible home. There is no uniform standard tool. It is a fragmented ecosystem.

Compliance is difficult in part because we don’t have systems in place to allow different organizations, different coaches, and parents to be able to talk to each other about their players – to be able to have the full picture of data on a player.

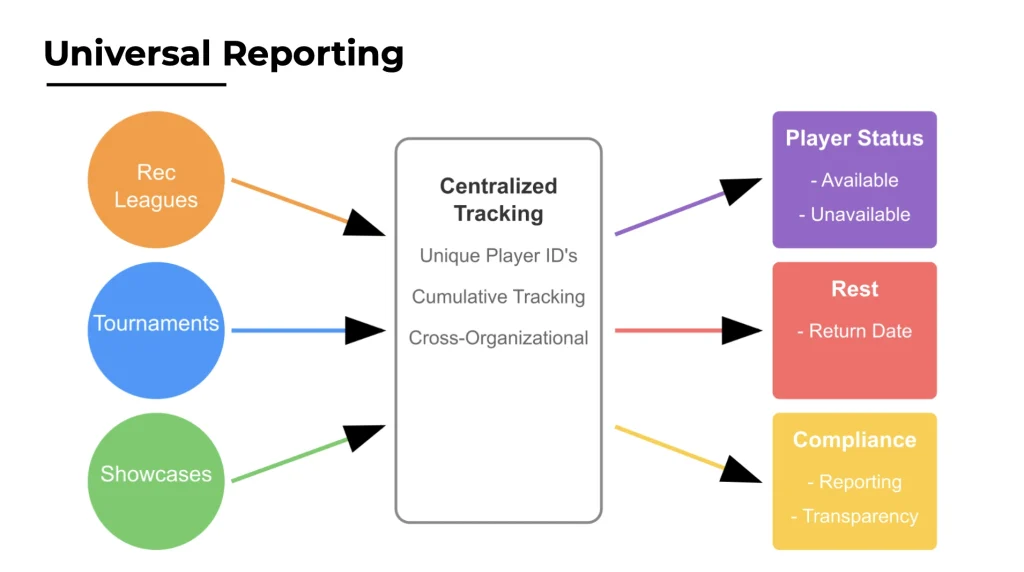

Morgan has a vision for a system.

“For the participating organizations, if a kid pitches on Thursday in a rec game, their availability for the weekend… would be informed by what’s happened previously,” he said, “Instead of what we have now, which is the right hand and left hand simply don’t talk to each other.”

Exacerbating the youth injury problem is there is a shortage of kids who can pitch – or, rather, that coaches trust to pitch. We often hear about how there is a pitching shortage at the pro level but Morgan says the shortage is even more pronounced at the youth and amateur levels, with coaches not developing enough arms, only trusting a few athletes per team, which can lead to a vicious cycle of overuse.

“If you’ve got a team of 12 kids on a youth baseball team, odds are three of those 12 are getting wrecked,” Morgan said, “because, again, the problem with the whole environment is that nobody has enough pitching. So, the kids that can pitch, and can pitch competitively, end up getting overused because of what is largely a (developmental) skill issue.

“Pitching is hard, and the game depends on it.”

But if there were universal reporting standards and rules, it would force coaches to develop more pitchers.

(Morgan notes a mandatory practice ramp up before games would also be beneficial in helping develop more pitching options. Coaches often need more time.)

So, step one is giving all parties access to the same information.

Step Two creates uniform standards.

“What we’re trying to push forward for universal pitch counts, universal reporting,” said Morgan of various age and competition levels.

Research conducted by Dr. Peter Kriz highlighted the U.S. States have wildly different pitch count rules for high-school-aged players.

“He put out a spreadsheet that lists all 50 States and all of their different pitch count standards,” Morgan said, “And it’s a disaster. It’s a complete disaster.”

What youth baseball needs is both universal reporting and universal standards housed on a centralized hub that can easily be pulled up on a smartphone.

“It’s got to be based on an app, right? So, it’s something that’s a little bit different than just like printing out a PDF and hanging it on a wall,” Morgan said.

There should be some flexibility, too, Morgan said.

There should be a standard for, say, the Little League pitcher who might only play baseball in the spring, who might not have the interest or wherewithal to employ a device like PULSE.

And there should be different workload guidance for an athlete more involved in baseball, playing on more teams, more serious about skill building.

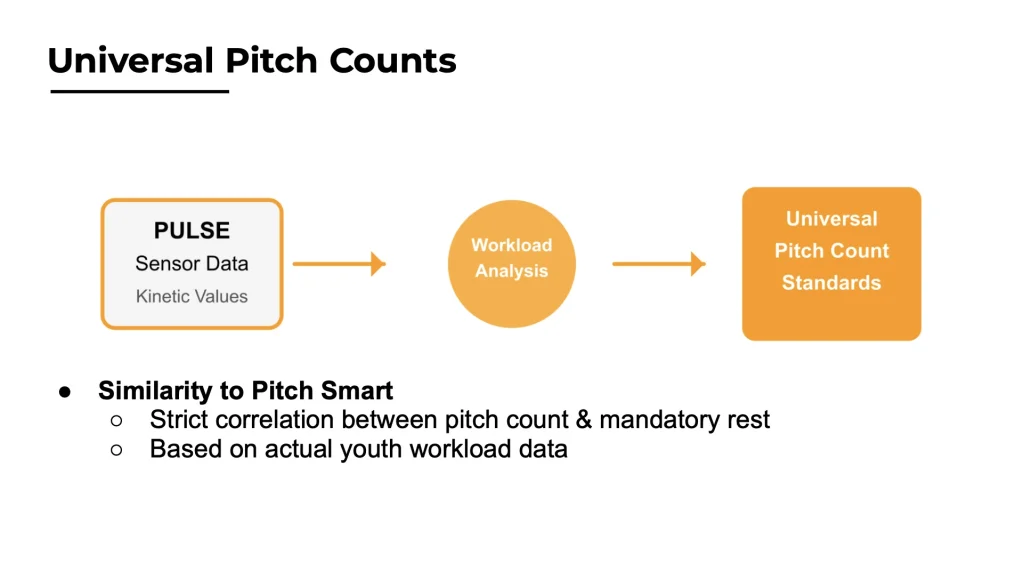

But without more data, we cannot know what those standards should be, and that’s where PULSE comes in.

For a long time, the best measure of pitching workload in baseball was pitch counts.

But that hardly captures the whole workload of a pitcher. The industry had no idea of the strain and stress accumulation of all throws until PULSE came along.

But with the wearable technology, for the first time, the force of every throw a pitcher makes can be measured and recorded.

We can even simulate the workloads of pitchers who are unable or unwilling to use the wearable tech.

PULSE also allows us to measure the force of each throw, resulting in a metric called workload units. There is more intensity tied to a game-day pitch than during catch play, or a bullpen session – and now we can quantify the difference. We can then add up the stress of an entire day’s work, to better understand the total stress of pitching and how to manage workloads.

While we have a good idea of the stress on professional pitchers, we have less knowledge on workload guidance for youth pitchers.

Again, we need more information.

Driveline is studying the data from the youth pitchers we do have, which is incredibly beneficial. But by broadening the sample, PULSE could help set more accurate guidance for youth and amateur arms of all ages. With that data would come great insights.

“I think the first layer of universal pitch counts is that you have to have a PULSE-driven standard where you’re actually using the workload data,” Morgan said. “And from there, data-based recommendations that correlate volume of throwing with the prescribed amount of rest for that specific workload can be made.”

But until that starts youth baseball is flying blind.

“We’re not quite sure what the data is going to show,” Morgan said.

Morgan cited a possible guideline scenario in which an 11-year-old pitcher could only be permitted to have frequent game usage if having gone through prolonged period of carefully building up his workload, and that there was a commitment to monitoring workload number to ensure it remained in an acceptable place.

But we cannot build a smarter pitch count for youth arms until we have more data. The good news is the industry understands the problem, and the technology (PULSE) exists to help quantify and thereby set guidelines. The tools are there. The interest is there. PULSE gives us a way; the industry just needs the will.

Comment section