How high school pitcher Noah Coury added 20 mph, and used PULSE to build his workload

Noah Coury represents both a classic Driveline success story, while also being an example of what is next in data-driven development.

Now a senior at Hazen High (Wa.), the right-hander pitcher began training at Driveline’s Seattle-based facility four years ago. He arrived as a rail-thin 135 pounder who could max out in the low 70s with his fastball.

“The first thing they said to me was, ‘Wow, you need to eat some more food,’” Coury said, “and they still tell me that.”

Progress often begins with a strength improvement plan whether training a major leaguer like Trevor Rogers or a high school athlete.

Today the 6-foot-4 Coury weighs in at 187 pounds. That strength gain in part fueled a remarkable velocity increase with Coury adding 20 mph to his fastball from when he first walked in the doors of our facility.

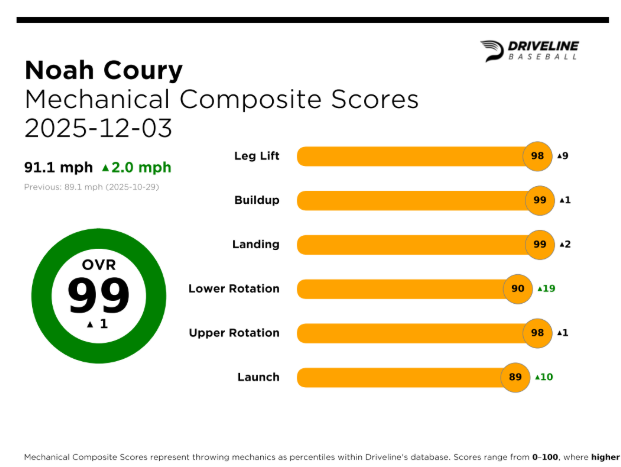

While Coury is a good athlete whose mechanics did not require an overhaul, there were refinements made to help him reach the 99th percentile in his overall mechanics score.

The plyo ball drills were an immense help in improving efficiency, he said. A few other of Coury’s favorite practices include the janitor drill to build better lower-body sequencing, and the walking windup to help him move faster down the mound. Increasing his speed down the mound was key, along with greater mass, for building velocity.

“With both of those (drills) if you get really pushy with your toe and your quad, then you’re going to, one, lose velocity and, two, you’re going to be off balance,” Coury explained. “Those were really big issues for me early on when I was like 14. Those two drills really helped me.”

For the last year, Coury has worked with Driveline’s Noah Ferguson as his primary trainer.

Ferguson said Coury has shown rare dedication and detail in training and arm care, and now their focus is largely on refinement and building his workload.

“I think one of the biggest things that we’re still kind of working on is his lead-leg block,” Ferguson said. “He moves down the mound so fast, and he rotates so fast, that for somebody that’s 180 to 190 pounds, especially as he was coming up, his lead leg just could not support all the force that he was putting into it. So, I think slowly working on some lead-leg block stuff has been a big focus and making sure that we are able to send energy up the chain a little bit more efficiently.

“But that’s really the only big mechanical deficiency that I’ve seen with Noah since I’ve been working with him. And the biggest thing for me is just keeping him out of his head and making sure that he just stays athletic. He’s such an athletic kid. … Just making sure that we’re not getting too focused on the way our body’s moving internally.”

While Coury has gained throwing velocity like many who have trained Driveline, he is also something of a trailblazer. He is one of the first prep athletes to be dedicated to PULSE usage and monitoring over multiple years.

He began using our PULSE technology nearly four years ago when he began training at Driveline when he was at the 14U level.

PULSE is incredibly valuable at the professional level, but it’s arguably even more important at the amateur level. The prep level is also dealing with elevated injury rates, but it’s where there are fewer resources available and less data to study.

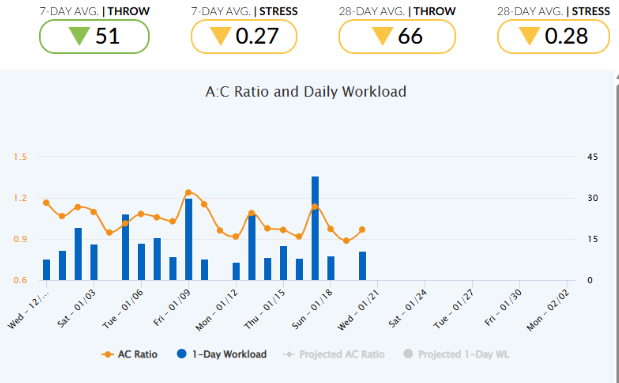

PULSE takes the guess work out of workload while giving an athlete guardrails to work within.

PULSE allows us to measure the force of each throw, resulting in a metric called workload units. For instance, there is more intensity tied to a game-day pitch than during catch play, or a bullpen session – and now we can quantify the difference.

PULSE also accounts for all the throws within a day, compiling them so we can measure the stress of an entire day’s worth of work. We use that monitoring to keep an athlete in a safe, age-appropriate workload range whether he is building up to begin a season, or in the middle of competing in one. We can now better understand the total stress of pitching and how to better build up pitchers and keep them healthy.

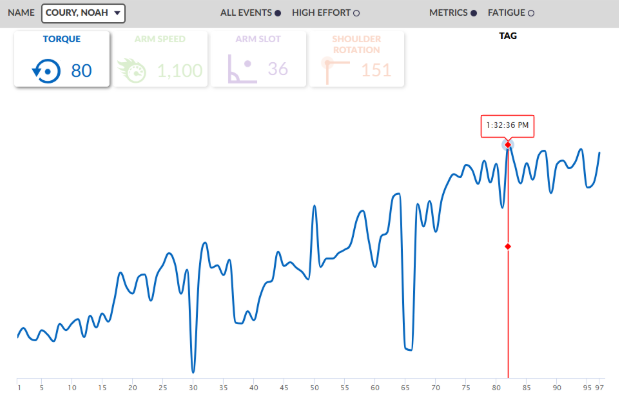

Coury also found PULSE to be an incredibly powerful tool during the last year when he began working his way back from a fluky injury.

About a year ago, Coury unleashed a pull-down throw at Driveline, which culminated with a front flip, an acrobatic way to decelerate. But when he planted his right arm on the ground to brace himself, he hyperextended and injured his right elbow.

PULSE was key tool before the injury as he added 20 mph in three years, and even more important as he built himself up following injury

“I think the biggest thing that’s beneficial to me is kind of wearing it on the recovery days,” Coury said. “That’s a big thing where I can monitor how much I’m throwing on recovery days, because if I’m only throwing like 50%, 60% (effort), I can easily go and make 100 throws at that effort, and I wouldn’t notice, which would be a high workload.

“I just try and stick as closely to the recommended workload as possible.”

PULSE gives Coury the confidence to know when he should throw, how much, and at what intensity.

“I would tell (younger guys) to make sure you stick to the workload because elbow injuries suck. They’re not fun,” Coury said. “And an extremely easy way to get them is doing more than you are supposed to, especially on those recovery days when your body is supposed to be actively recovering.”

Ferguson has seen the power of PULSE in working with Coury and other athletes.

“The biggest thing right now with him is our recovery days because his mechanics are so good, it’s really easy for him to get up above that threshold that we want him working at,” Ferguson explained. “PULSE gives us a really effortless way to monitor that workload on a day-to-day basis, especially on those lower-intent days.

“He knows on what days, what ranges he needs to be in.”

Ferguson notes PULSE can measure the stress of every type of throw, including those not made on the mound during recovery days.

Like many high school athletes, Coury pitches and plays a position on the field, usually first base.

PULSE allows for all his throwing work to be measured, not just pitching-related training.

“On those recovery days, when I don’t want him throwing out of his wind up, or his stretch position but we’re trying to keep him athletic, PULSE allows us to monitor the workload,” Ferguson said. “We can get a gauge on that and be like, ‘OK, he is doing some shortstop throws, or he’s doing some catcher throws. How does that impact his workload today compared to normal throwing?’ Monitoring that acute-to-chronic ratio and making sure we are staying in a good spot especially for a guy coming off elbow problems … building that workload slowly.”

Recently, Coury returned to the mound for a motion capture and his first high-intensity throwing since he was injured. He was elated to see 90.4 mph light up on the velocity board after one of his first four-seam offerings.

“It honestly wasn’t even the number that made me excited,” Coury said, “It was honestly just being off the mound again. That was my first time being off the mound in a full year, like at 100% and. … I more so wanted to make sure that I felt good after that mocap, and I didn’t feel like my arm was in pain, that kind of stuff. And I felt great after.

“I’ll retest in two weeks and hopefully I can put up like 94 (mph) or something like that and that would be awesome.”

That would certainly open some eyes among college coaches. Coury’s goal is to pitch at Division I level.

He has not had as much game action as he would have liked due to his fluke injury, but he enters his senior year with his best days ahead of him as a pitcher. Coury is a classic Driveline development success story, with plenty of chapters yet to be written.

Comment section