How power ages (It might surprise you)

Conventional wisdom posits that power improves with age. It suggests slugging prowess is a rare skill that ages well, becoming better with time.

The thinking goes something like this: When a professional player reaches his late 20s, he will mature, acquire his “man strength” as some describe it, and his power capacity will peak.

I was curious to test this notion. Is it true?

And, moreover, how do the underlying skills that support power change with time? With the help of our own Jack Lambert, we explored.

What we found might surprise you. And what we can learn from it from a developmental perspective is fascinating.

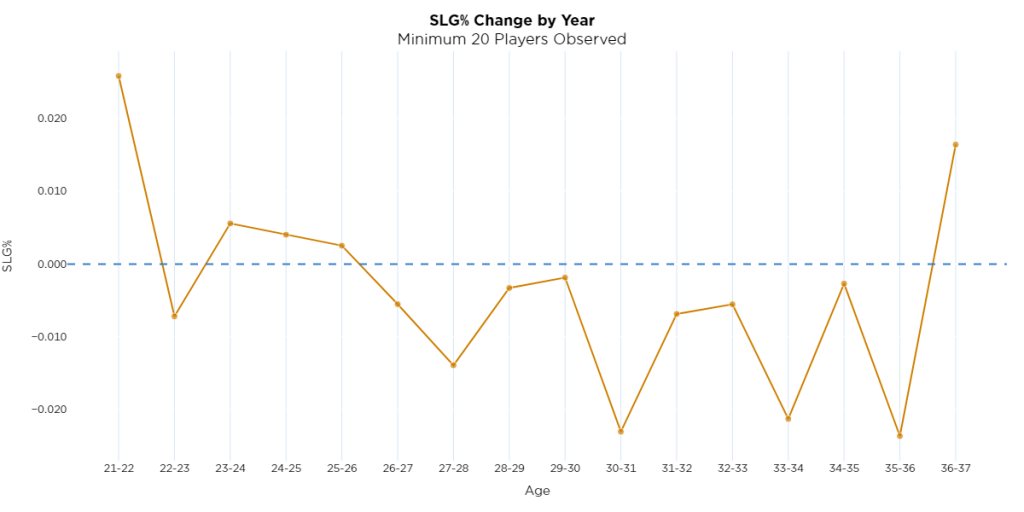

Let’s begin with the most traditional way to measure power ability: slugging percentage.

It turns out that slugging doesn’t improve with time.

We evaluated all player seasons during the Statcast era (2015-present) that included at least 1,000 pitches seen in a season and studied year-over-year changes among those qualifying seasons. By the time a player reaches 26, slugging declines by about 10 points a year. That’s supposed to be smack-dab in a player’s prime in the traditional way of thinking about a player’s career arc.

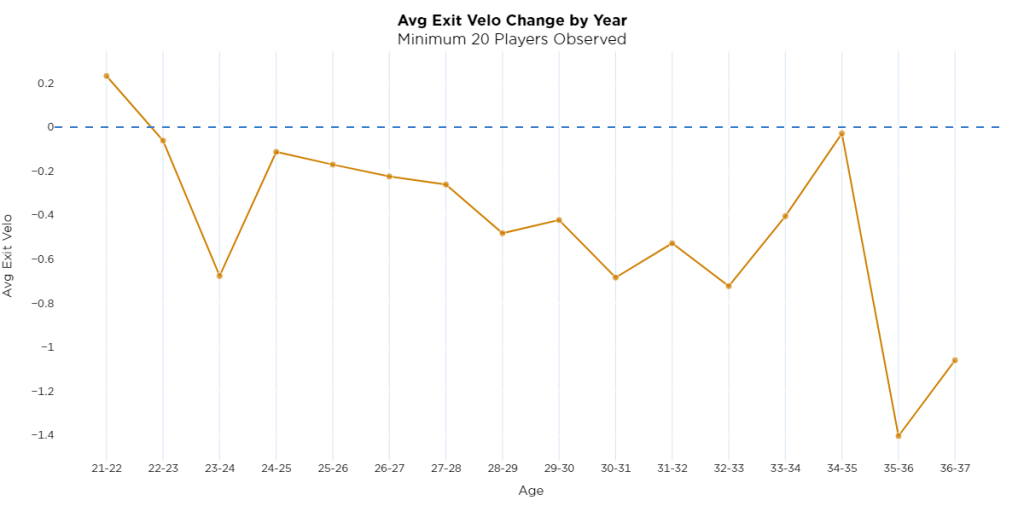

We also studied the underlying skills that generate power, and it turns out most of them do not age gracefully, either, with one notable exception.

Consider exit velocity. It declines immediately:

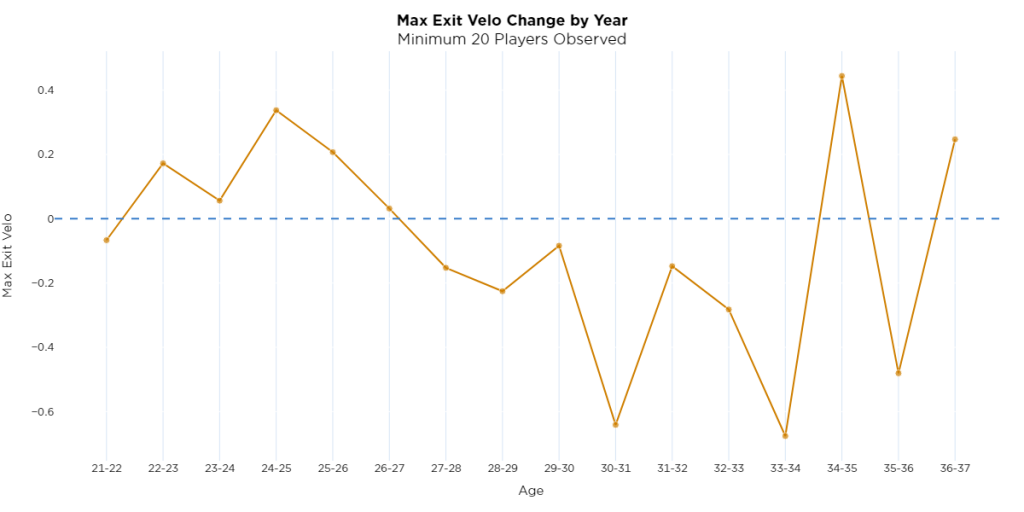

Max exit velocity is a little different. It ticks up to a peak near a player’s age 26 season and then begins to decline, with decline accelerating at age 31.

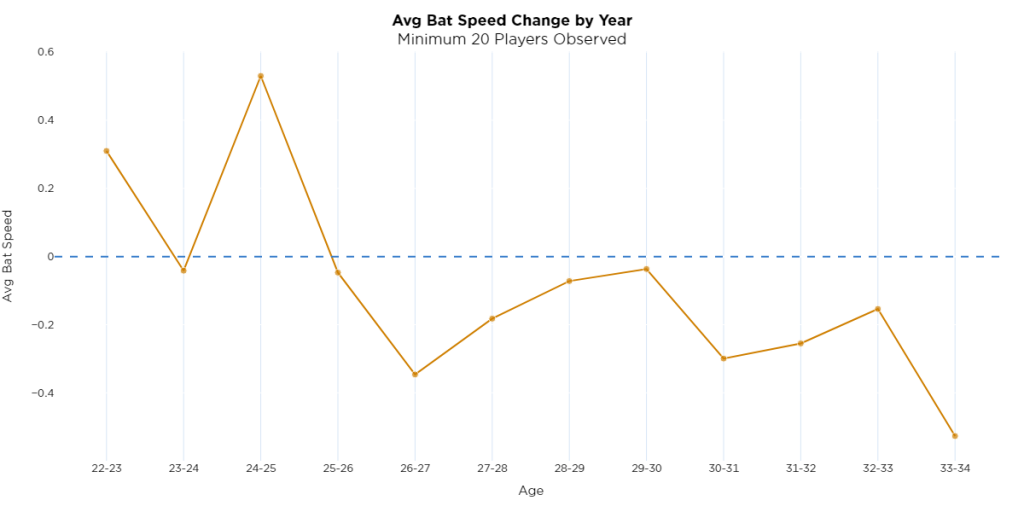

Bat speed? It also peaks early in a career, at age 25, and then begins a slow, tapered decline through a player’s 20s. Like with many skills, the decline steepens in a player’s 30s.

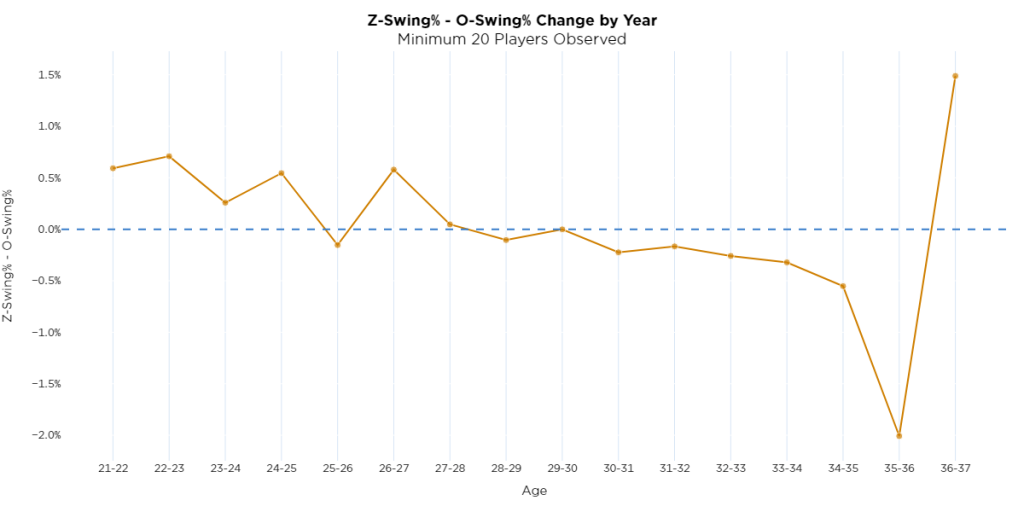

What about swing decisions? Surely those must improve with maturity, experience? Not exactly. They remain relatively stable with slight growth during a player’s mid 20s followed by a gentle decline until a player’s mid 30s.

Position players are not becoming stronger in their late 20s, as conventional wisdom suggests. Bat speed and exit velocity are not immune to aging like so many other movement- and speed-based skills in the sport (like pitching velocity).

When players arrive in the major leagues, many of their underlying skills are nearly as good as they will ever be – at least since we’ve had the ability to measure them in the Statcast era.

Driveline director of hitting Tanner Stokey noted that those skills’ aging curves might have been different years ago – perhaps more players did grow into strength and bat speed – but it is a different game in the modern era.

“You just assume players are the most physically gifted they’ve been – they have all the resources in the weight room, the nutrition side, the sleep, recovery side, right? It’s very different than it was back in the day,” Stokey noted. “That stuff is pretty optimized compared to where it was 20, 30, 40 years ago.

“That might’ve been true back in the day (power developing later) but we obviously don’t have the technology to get that data from back in the day.”

Knowing that underlying power – bat speed, exit velocity – decays with time, how does this change how we should think about hitting for power, and how to train it? And how does that explain players who do enjoy upticks in power later in their careers?

Let’s consider the case of Kyle Schwarber.

The Phillies’ slugger enjoyed his best season at age 32, building upon what was already an impressive resume. He belted a career-best 56 home runs along with a 152 wRC+, the top mark of his career.

He’s always been a curious player, wanting to challenge himself to get better.

For instance, back in 2016 when he missed almost the entirety of his second season after tearing his ACL early in April, he began a regimen of just watching pitches from a Hack Attack pitching machine later during his rehab – hundreds upon hundreds of them. He watched pitches of various speeds and shapes and would call out whether he estimated them to be a ball or strike. A Chicago Cubs official graded his decisions.

He was trying to maintain his batting eye even when he couldn’t swing.

He returned for the World Series when he hit .412 with two RBIs in five games to help the Cubs end their curse. That 2016 swing-decision cram session was designed to try and allow him to make an impact in the postseason. But Schwarber has always looked to improve.

“I have to evolve and be better. I cannot always be the same,” Schwarber told me earlier this season. “You have to get better at some point or the game is going to catch up with you. You have to be a really good self-evaluator. You always have to get better at something.”

He’s an example of a player defying the age curve.

Schwarber has always crushed baseballs with well above-average exit velocities. He’s an outlier in that he enjoyed the best average EV of his career this season (94.4 mph). He’s also posted the second-best max EV reading of his career, and his bat speed is only slightly down from its recorded peak.

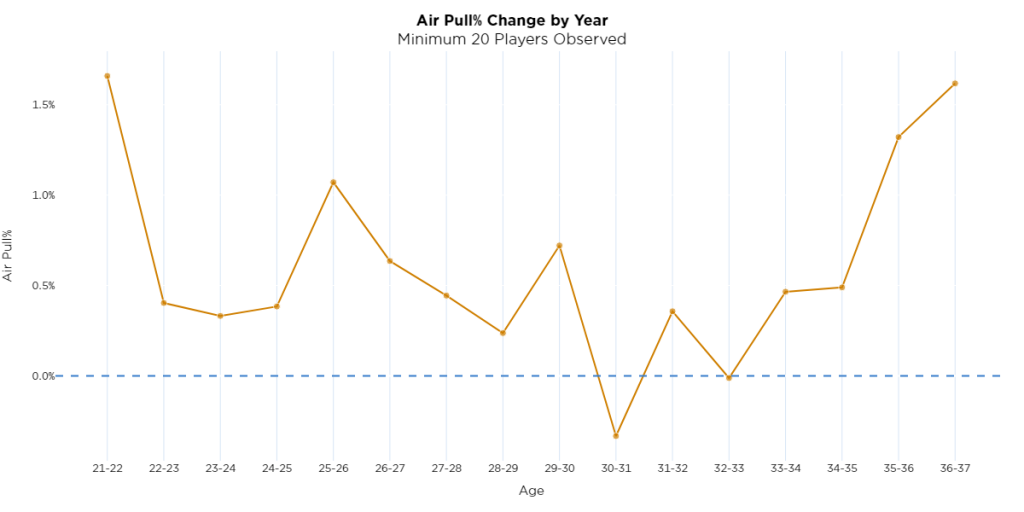

But he’s been able to get much better later in his career in one skill that does age well: pull-air percentage.

The question becomes whether more younger players access pull power earlier in careers via more training focus, with help from tech breakthroughs like the Trajekt pitching machine which creates more game-like reps.

Could Schwarber have become the 45-plus home run hitter he’s been in recent years earlier in his career? What if he was training with Trajekt in 2016? Or is there no substitute for game experience?

I asked Driveline assistant hitting director Andrew Aydt if hitters earlier in their careers can pull forward the pull-air spike we see later in careers.

“I think it can definitely be accelerated,” Aydt said. “That’s definitely something that we worked on with hitters is to be able to learn to pull the ball in the air and more consistently and correctly and know when to take your shots in certain situations and counts.”

Every hitter who takes a swing at Driveline almost always has a target they are tasked with trying to hit. And that target is often in the air, to the pull side.

Training has changed a lot in recent years and will have a great impact on development trends.

“When you’re growing up, most times you do not really ever have any coaches telling you to pull the ball in the air,” Aydt said. “It’s always, you know, ‘Hit line drives up the middle’.”

Few players came to realize the benefits of a pull-air approach on their own pre-Statcast like J.D. Martinez did, which led him to a major swing change and remarkable 2014 breakout. Martinez told me this back in 2017: “You still talk to coaches ‘Oh, you want a line drive right up the middle? Right off the back of the [L-screen in batting practice]?’ OK, well that’s a fucking single.”

It’s different now.

While many players were perhaps not sure what to do with Statcast data when it debuted in 2015, everyone is now aware of where batted-ball flight is optimized.

There were 5,532 pulled fly balls in the 2015 season compared to 9,198 this season, a 66% increase. Average launch angle has improved from 11 degrees in 2015 to 13 degrees this season.

So perhaps the pull-air aging curve will look different a decade from now.

If that is true it would seem to place older players at an even greater disadvantage, and further stress that cohort of players.

But we also don’t want to assume that skills must remain static, that a player cannot empower himself through different training approaches to better stave off Father Time.

Older players can improve bat speed and exit velocities – it can be especially impactful if such players are new to such training regimens.

Consider the cases of Mookie Betts and Nolan Arenado, both of whom trained at Driveline.

In late August of 2021, Arenado singled against the Reds and had a few moments to chat with Joey Votto at first base. Arenado was curious how the Reds’ then 37-year-old first baseman had a late-career resurgence. Not only did Votto slug 36 homers that year after years of power decline but Arenado noticed his exit velocities had spiked, too.

“I was like, ‘Dude, what’s going on? You’re hitting the ball ridiculously hard,'” Arenado told me in 2022. “He was hitting 117-mph bullets last year, and he was 37.”

Votto told him his secret, his fountain of youth: bat-speed training.

Arenado traveled to Driveline after the season and posted a 149 wRC+ and 7.2 fWAR in the following campaign, his age 31 season – the best marks of his career.

Recently, Arenado had a motion capture at Driveline’s Arizona complex and intends to train with us again this offseason.

Stokey worked closely with Betts in 2023 when Betts enjoyed a two-mph spike in exit velocity that year, averaging a career-best 92.4 mph at age 30. It was key to his success as he launched a career-best 39 homers and produced a 165 wRC+.

Betts’ resurgence this season began with a renewed focus on bat speed training in mid-August.

They prove a player can improve bat-speed and underlying power skills in their 30s.

Stokey said bat speed training ideally begins earlier in careers but that it’s “important for all ages.”

That leads us to an interesting question: what would power aging curves look like if every player employed bat-speed training their entire careers? After all, the future is going to include such regimens becoming increasingly commonplace.

“My best guess is the starting point is going to be higher,” said Stokey of bat speed. “The baseline is going to be higher, and (bat speed) probably won’t fall off as drastically. Maybe the point of when it falls off moves back from like 29 to 31, to like 32, 33, 34. … It’s going to start to taper off in a similar fashion, but it might get pushed back a couple years until it really falls off a cliff.”

That’s likely what the future will look like.

Youth will always be an advantage but if hitters can flatten the aging curves, and push back dramatic fall off, that has major implications for how players can fare in arbitration and free agency.

It’s possible that the next decade of data will create evolving aging curves but what we do now is that players who are not increasing bat speed, that are not focused optimizing batted-ball flight, are more likely to be left behind.

Comment section