The Many Swings of Bryce Harper — And The One Swing of Nick Kurtz. How many clubs should hitters have in the bag?

In the spring of 2013, former Washington Nationals hitting coordinator Rick Schu was collecting iconic swings from DVDs of Ken Burns’s “Baseball” series, a Christmas gift from his wife. He explained to The Washington Post he wanted cutups of some of the best swings of all time, and a dozen years ago, this was one of the more efficient ways to gather them.

And as he watched the grainy, black-and-white videos he was struck by something: did Bryce Harper have the same swing as Babe Ruth?

He arranged clips of Ruth and Harper side by side and noticed that they took a similar stride, landing with the same stiff front side when their back foot left the ground. Their hips, then bats, uncoiled in a blur.

“They’ve got that exact same swing at contact point. Identical,” said Schu, whose observation led to the newspaper publishing a piece titled “A Swing of Beauty” based upon Harper’s “exquisitely ferocious swing” as described by writer Adam Kilgore.

Harper didn’t land on the cover of Sports Illustrated at 16 because he sprayed line drives around the field. He became arguably the most hyped prospect of the 21st century because he hit nukes. That swing led him to become the first overall pick in 2010, to become the NL MVP at age 22 in 2015, and it allowed him to live up to incredible expectations.

A few weeks ago, I asked Harper how his swing has changed from his early pro career. Harper said it’s not so much that his max-power swing, his ‘A’ swing changed, rather, it’s that he now possesses multiple swings.

“I think for me it’s I have more clubs in the bag,” Harper said. “There are times when I do a toe tap, times where I do a leg kick, and times where I do a two-strike approach. So, I have those clubs in my bag, right? Just like a golfer has a seven iron, or a pitching wedge, or a driver. I am one of the ones in the game who changes their swing a lot from one day to another.”

How many swings should a player have?

How much training economy should be used to develop something other than trying to launch a ball in the air to the pull side? How often should someone like Harper be going away from that exquisitely ferocious swing?

Even with his assortment of swings, Harper still hits for plenty of power.

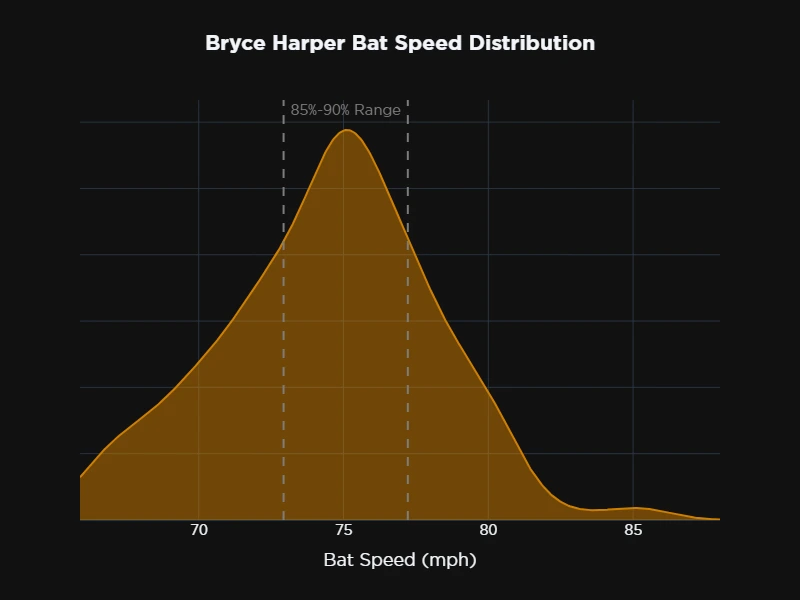

Since bat speed has been tracked, he’s ranked in the 84th percentile or better.

Since his debut, he ranks 7th in the majors in home runs (351) and 9th in wRC+ (142).

The complete body of work is exceptional.

But he also does not always seek to sell out for power, not anymore.

One interesting aspect of this development, or multiple clubs as he calls them, is his two-strike approach.

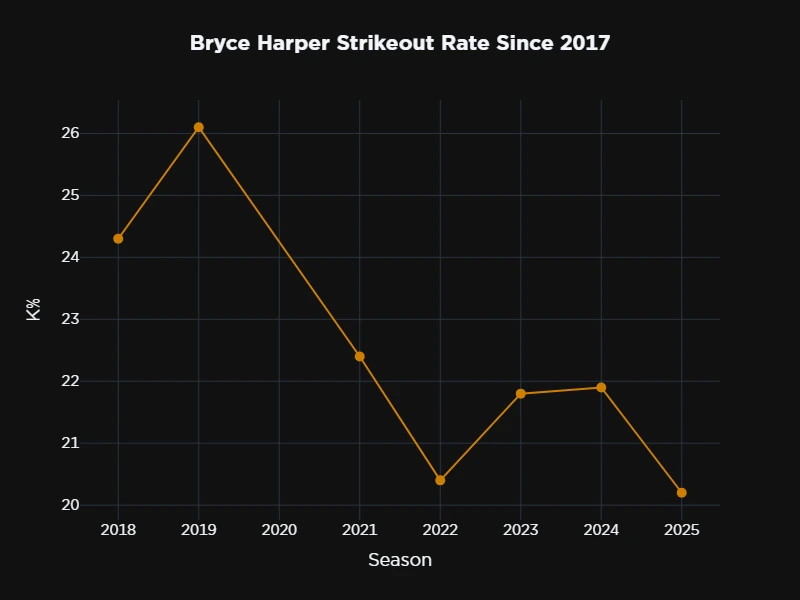

In recent seasons, Harper has tried to reduce his strikeout rate, and he is enjoying his lowest non-COVID season strikeout rate (20%) since 2017.

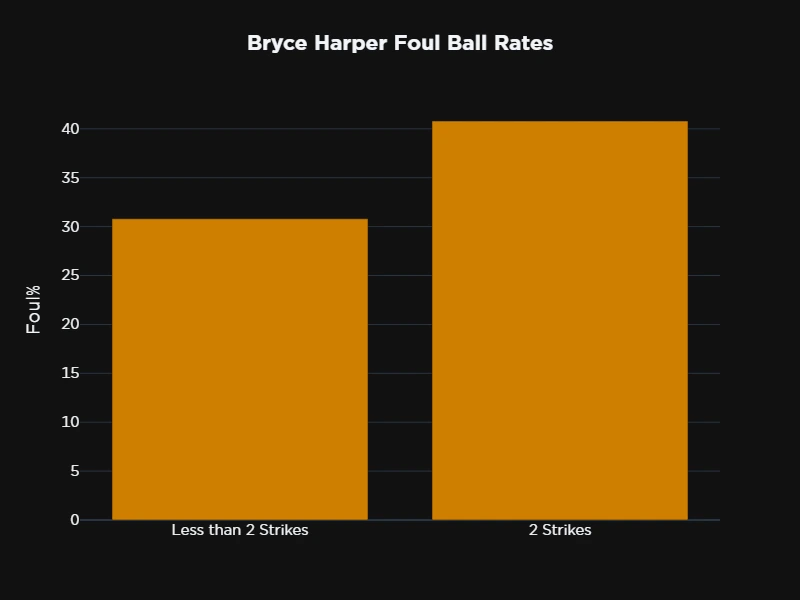

With two strikes this season, Harper’s foul-per-swing rate increases to 40.8% from 30.8% with less than two strikes. That ranked 37th out of 506 batters to have seen 100 pitches this season at the All-Star break.

It also makes his the highest two-strike foul ball rate on record at BaseballSavant.com.

He’s become better at spoiling pitches, and more often uses the whole field as his pulled batted-ball rates have declined.

This season his pull rate is more than seven percentage points lower than its 2015 peak. His hard-hit rate on fly balls over the last two years (40.2% last year, 42.3% this year) are some of the lowest of his career, and well below his career-best rate of 53.4% during his 2021 MVP season, and his 49.4% rate in 2015. It suggests he is trading some power for accuracy in certain counts.

Scott Boras, Harper’s agent, told me last spring he advocated for Harper to change his approach with two strikes.

“I went through this (in the 2022-23) offseason with Cody (Bellinger). He’s hitting .060 or .080 with two-strikes. I said, ‘Cody, this can really increase your average,'” Boras said.

Bellinger hit .141 with two strikes in 2022, improving to .279 in 2023.

“I did this with Harper, too. ‘With two strikes, be contact orientated. You are a great athlete. You have tremendous hand-eye, use your contact skills. ‘ He can run. His hard-hit rate dropped off because now, instead of striking out, he’s making contact and getting on base,” Boras said. “You don’t want guys who swing and miss, you want guys who get on base, but their hard-hit rates drop when they do that. He hasn’t diminished his power.”

But there is a trade off in having different approaches.

To be clear, Harper is still one of the game’s best hitters. No one would argue that. But his top home run season came back in 2015 (42), which was also his best campaign in terms of slugging (.649), pull percentage (45.4%) and wRC+ (192). He’s had more seasons with fewer than 25 homers (7), than exceeding that threshold (6).

Perhaps Harper should employ his driver more often.

While his two-strike wOBA improved from .239 in 2023 to .307 last year, it’s dipped to .267 this season, which is below his career mark (.289).

His overall contact rate is actually below his career average this year after a spike last season.

When, if ever, should hitters go away from their ‘A’ swings? How often should they go away from an intent to do damage?

I posed the question to two vastly different but excellent hitters in the A’s clubhouse this season: Jacob Wilson and Nick Kurtz.

Wilson possesses one of the shortest swings in the majors and has been at or near the top of the hits leaderboard all season thanks to his elite eye-hand skills and exceptionally low strikeout rate. (He went on the IL with a fractured forearm on July 29).

He says his contact skills were honed by competing against his dad, former major league Jack Wilson, in their backyard batting cage when he was a kid.

“My dad would always try to strike me out,” Wilson said. “He was very competitive with me. Just learning how to hit that stuff when I was 10, 12 years old helped me become the hitter I am today.”

Wilson said he has two swings: his regular swing and his two-strike approach.

“There are two clubs in the bag,” Wilson said. “With two strikes, I just stay short to the ball. Try and foul off everyone’s best pitch and stay in the battle.”

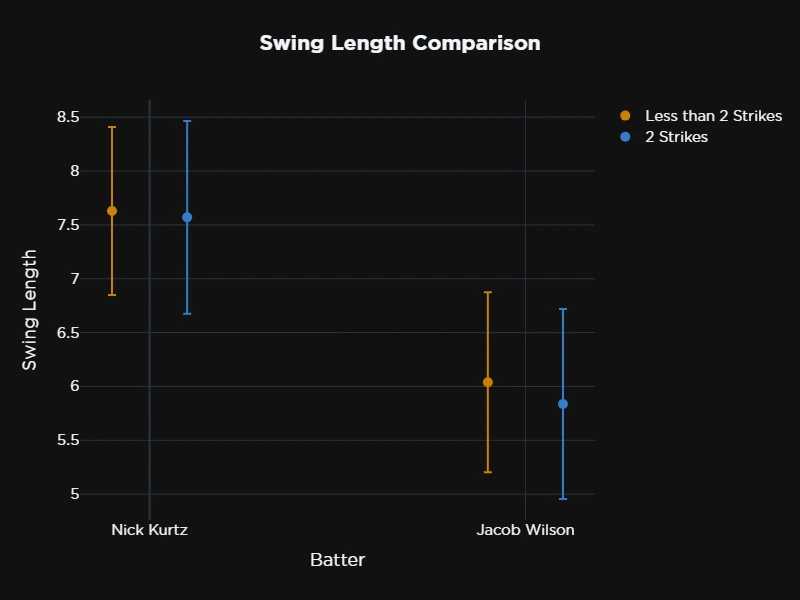

Wilson has one of the shortest swings in the leagues. It’s even shorter with two strikes (5.9 feet) than other counts (6.1 feet).

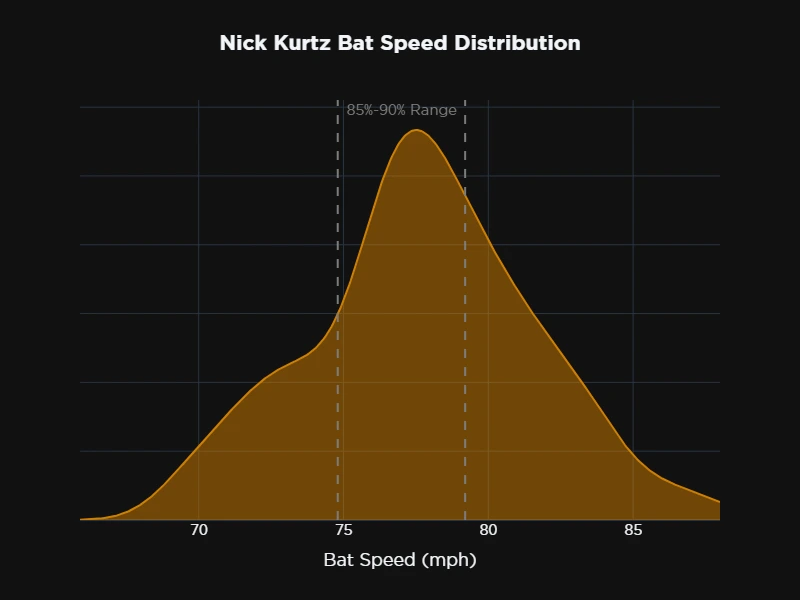

On the opposite end of the raw power spectrum is Kurtz, who became the 20th major leaguer to slug four homers in a game on July 25, and since June 1 leads the majors in wRC+ (223). He’s only played 71 games entering play Saturday and is tied for the MLB lead among first basemen with 23 homers.

Kurtz says he has one club: his driver.

He swings with such force that his batting helmet is often toppling from his head, exposing a mop of wavy hair.

His swing length (7.7 feet) is the same with two strikes as it is when he is ahead in the count (7.7 feet).

"I don't do a lot of changing -- For me, the more I change the more opportunities I have to screw something up. Maybe against some left-handed pitchers I might make an adjustment to stay on the sweeper, something like that, but for the most part when the foot is down and ready to go, I like to be the same all the time."

Nick Kurtz

Kurtz ranks 87th in two-strike wOBA (.269) among the 421 hitters to face at least 100 two-strike pitches this year. Harper ranks 99th this season (.264).

I posed the same question to Driveline Director of Hitting Tanner Stokey. How many clubs should a batter have in his bag?

“If Bryce Harper, early in the count, is taking ‘B’ swings, I think that is a problem,” Stokey said. “I guess it’s a little bit different if it’s in the NLDS and there’s a runner on third base in a tie game in the seventh inning. But then again, early in the count, you have the ability to score two runs on one swing. You should be getting your ‘A’ swing off.”

Two core hitting tenets at Driveline are improving bat speed and bat path.

The greater the bat speed, and the more optimal the bat path, the better the offensive performance.

But that does not mean batters should only train to hit the ball in the air to their pull sides, or what might be defined as their ‘A swing.’

Stokey wants hitters to increase their margin for error. After all, it’s difficult to be perfectly on time with every swing. That means it’s a benefit to have a swing, or swing types, that can adapt in real time and do damage to all parts of the field.

There are benefits to creating different types of ball flight in training, Stokey said.

At Driveline, hitters are often given a variety of batted-ball targets. They are not always focused on hitting the ball to the air to their pull side.

“As much as we talk about bat speed and pulling the ball in the air, you’d be pretty surprised how many times we hit it hard and low to the opposite field,” Stokey said. “Backing up the point of contact, catching the ball deep, and sequencing well enough to be able to maintain posture and get the barrel on plane behind it … Hard and low to the opposite field – it’s going to help them reverse engineer a way to have a good efficient path to when they catch the ball out in front.

“A lot of it comes back to ways to increase your margin for error as a hitter.”

Consider the case of Rockies outfielder Jordan Beck, who worked with Driveline last offseason. He was curious, he said, to “learn about other avenues that I don’t know well, or don’t understand.” What he learned was that his bat path was too steep entering the zone.

“It was like I had a shorter window to get the ball in the air,” Beck said. “We worked on trying to give myself a longer window to get the ball in the air. The best guys will get it in the air deep, or, out in front.”

And that included a variety of ball-flight targets.

The best hitters can be productive even when their swings break down, when they are caught out in front on a changeup, for instance, or protecting with two-strikes against a slider that darts into the shadow zone.

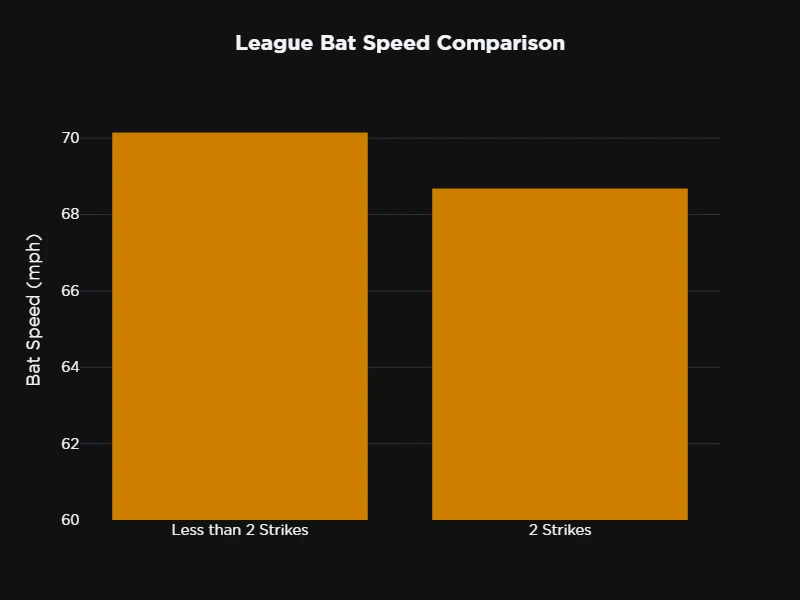

And all swings break down. With two strikes, MLB average bat speed declines 1.5 mph.

Hitters are not always going to get to an ideal contact point with their top bat speed.

Building the “engine” as Stokey calls, improving the underlying ability to produce bat speed, helps all hitters – whether getting to their best swings or not.

And what we have found is hitters at their best are not using 100% max-effort swings in terms of bat speed.

Rather, the best swing outcomes feature good but not maximum bat speed, suggesting some type of trade off.

“What we’ve seen from all the data is hitters’ performance is at their best, in terms of xwOBA, when they are at 90-95% of their bat speed,” Stokey said. “Part of bat speed training is we are trying to raise the ceilings so when you do take a little bit off, you are still moving the bat fast, you can still impact the baseball hard. Nobody is going to be swinging at 100% intensity at all times in the game. It’s just not going to happen. The game is too difficult, and it is not getting easier. As you can see, the league average offensive numbers have plummeted just because pitching has gotten so good and they can adjust so quickly. That’s another reason why hitting is such a beautiful nightmare.”

Kurtz is one of nine batters tied with a recorded bat speed of 88 mph this season. His average bat speed (77 mph) is 92.5% of his max swing. He is in that range.

That suggests he’s getting to his optimal swing often, and when he takes a little off, he still has plenty of power.

Harper’s average swing speed (74.5 mph) is a bit below the 90% level of his maximum bat speed (85.8 mph). He takes fewer max-effort swings than Kurtz.

Perhaps his multiple swings allow him to excel with less maximum effort swipes at pitches, or maybe he’d be a regular 40-homer bat with Kurtz-like swing speed distribution.

Perhaps some hitters need to take a little off, but others need to add a little more power, more intent to do damage.

Consider the case of Mookie Betts whom Stokey worked closely with in 2023. He wasn’t getting to his best swing often enough.

Bat speed training was a focus that offseason leading into the season, and Betts enjoyed a two-mph spike in exit velocity that year, a key to his success.

But with Betts there was also an important mindset change.

“The thing with him was ‘Man, your bat-to-ball skills are so good,'” Stokey said. “A lot of times you see players with very good bat-to-ball skills, they don’t want to swing and miss. So, while Mookie didn’t have poor chase rates he would expand on the edges and swing on balls in the shadow zones and slow himself down for the sake of putting the ball in play. He’d slow himself down and make poor, unproductive contact.”

Even the best hitters in the game might not have quite the right mindset regarding where they belong on the power-contact spectrum.

“One of the things that was really important to his 2023 season was the approach got really simple,” Stokey said.

They focused on crushing pitches inside, where Betts excelled, and getting to his best swing as often as possible. Power over contact.

“‘Do not be afraid to swing and miss. Because as the count gets deeper, your bat-to-ball skills are so good you are not going to get out-stuffed,'” Stokey recalled of the conversation. “‘Get your ‘A swing’ off as often as possible, because you have such an ability to impact the baseball, your ball striking is insane. …Dude, do not slow yourself down to put the ball in play before two strikes.’

“That shift in mindset over the course of a season makes a huge difference in performance. A huge difference in the ability to slug and do damage and that showed during the season.”

In 2023, Betts set a career high in home runs (39), raised his batting average and raised his wRC+ to 165 from 144. He also cut his strikeout rates. He finished second in the NL MVP voting.

Betts was already a great player but getting to his driver more often, using the golfing analogy, took him to an even greater level. One of Betts’ strengths is curiosity. As good as he’s been, he’s always looking to get better.

Hitting is, of course, very individualized.

Giancarlo Stanton should worry less about swinging and missing than Luis Arraez because of the amount of damage he can do when connecting, Stokey said. Some hitters also perhaps benefit from having more clubs in their bag.

But there is no substitute for building a better engine, and getting to an ‘A swing,’ as often as possible.

Comment section