An examination of Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s World Series Usage: Risky or perfectly safe and rational?

As FOX returned to its World Series Game 7 coverage of the bottom of the ninth inning back in November, the camera was focused on the new pitcher on the mound – Yoshinobu Yamamoto – making his final warm-up pitches. It was a remarkable sight.

Play-by-play voice Joe Davis shared with the audience that the only other pitchers to have appeared in a World Series Game 6 and Game 7 were Grover Cleveland Alexander in 1926 and Randy Johnson in 2001.

Said John Smoltz as Yamamoto readied to make his first offering to Alejandro Kirk with one out, and runners on first and second with the score tied:

“This is unbelievable. I know it’s all hands on deck but man oh man, here we go.”

It wasn’t easy.

Yamamoto hit Kirk with his second pitch, a 96-mph fastball, to load the bases. In the following at bat, Daulton Varsho stung a ground ball toward Dodgers second baseman Miguel Rojas, who stumbled upon fielding the ball. Rojas somehow stayed on his feet and threw home for a force out. The following batter, Ernie Clement drove a fly ball to the left-center warning track where Andy Pages made a remarkable catch, Randy Moss-ing his teammate Kike Hernandez. It was one of the most remarkable half innings in MLB history.

Yamamoto settled down and pitched a scoreless 10th and 11th innings to close the game and lift the Dodgers to back-to-back World Series titles. The effort marked his third win of the series – just the 14th pitcher in MLB history to do so – earning him World Series MVP and baseball immortality.

Johnson is the only other 21st century pitcher to win three games in a single World Series.

Yamamoto threw 130 total pitches over those two days, and 235 total pitches in the series – the seventh most pitches in a World Series on record.

This all came after Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said earlier in the day Yamamoto would not be available. Roberts reversed course with everything on the line.

“I’m kind of crazy for sending him back out there,” Roberts said. “But I just felt he was the best option.”

But was it crazy?

Could the Dodgers have known he would be effective in the most pivotal moment of the season?

Could they have reasonable expectations he would not be at extreme injury risk?

What can data insights from our PULSE technology tell us about such workload management? How can it guide coaches and players?

Driveline’s Max Engelbrekt, pro pitcher and Driveline researcher Josh Hejka, and this author were curious to study Yamamoto’s World Series workload. Was he pushed too far? Could he have been pushed further? What are the limits?

We investigated these questions for our second installment of an occasional series exploring pitching workloads.

Our first piece in the series was a hypothetical exercise exploring what it would take to build a Nolan Ryan-like, season-long workload.

This is a different case: that of an extreme short-sample workload spike that occurred in the real world.

If you have not read the Ryan piece, let us begin with a key metric that will guide us: acute-chronic workload ratio (ACWR). This workload guardrail will give us insight to understanding what Yamamoto did, and what he was capable of without taking on extreme risk.

It is a metric that compares an athlete’s training load over a brief period (acute), a week for a pitcher, to their workload over a longer period (chronic): the previous 28 days for a pitcher in our methodology. The concept of ACWR began outside of baseball, and research extends to a number of sports, too. Most athletic disciplines share a common finding: an athlete should increase their acute workload to build capacity, but not too quickly.

While there’s no single metric number that can safely prevent or predict injury, studies have found there is greater risk for a pitcher to sustain an upper-body injury when their ACWR is greater than 1.3, or a 30% increase in short-term work over their longer-term average.

To be extra safe in our simulations, we do not want our acute workload to exceed chronic by more than 20%.

To quantify pitching workload, we employ a measure called “workload units,” informed by PULSE, to give us an understanding of the stress of all throws a pitcher makes.

Different throws have different values. There is more stress and energy involved in making an in-game game pitch versus light throwing the day before a bullpen. That is straight-forward logic. But all throws add up. They all have value. PULSE allows us to measure the exact forces of all throws to tally and monitor a pitcher’s total workload. This goes well beyond pitch count data.

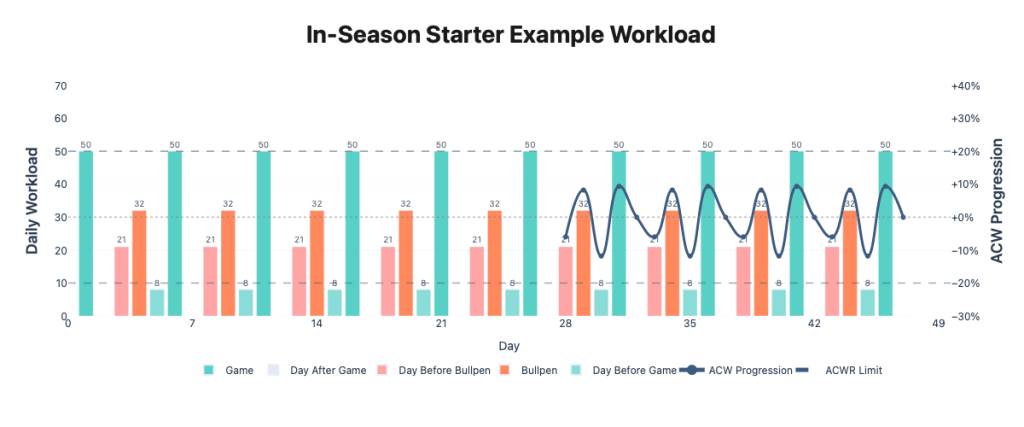

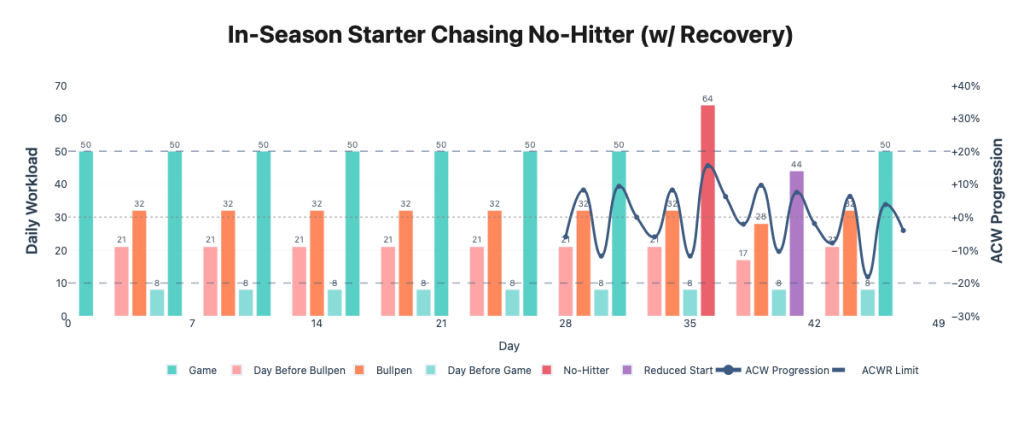

For example, the following is what a typical in-season workload looks like in terms of workload units and ACWR for a starter:

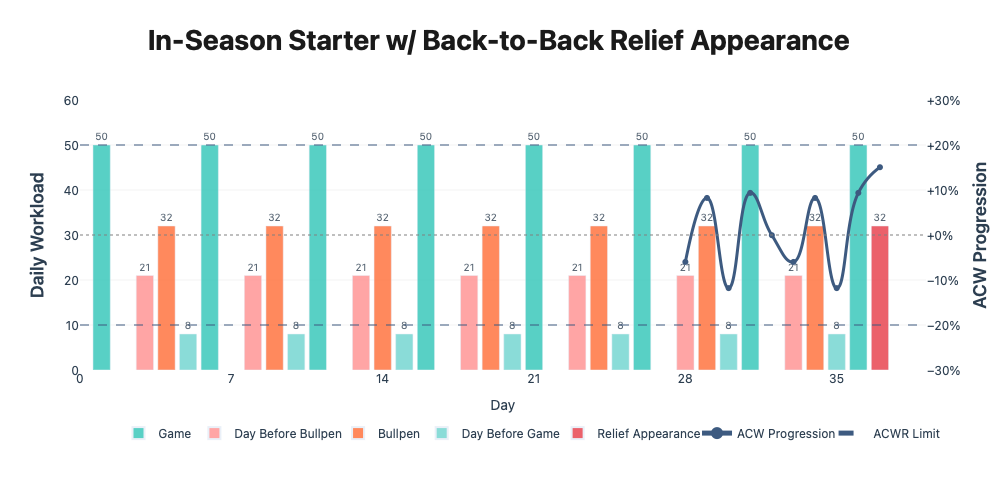

In Game 7, Yamamoto threw 34 pitches, which is just shy of 30 workload units. That is roughly in line with adding in-season bullpen day to what is normally an off day from throwing.

To be clear, we are not analyzing actual PULSE workload from Yamamoto. What follows are simulations based upon workload assumptions.

By Hejka’s calculations, this is what Yamamoto’s Game 7 looked like in terms of workload:

It turns out adding an extra, one-time 32-workload unit effort during what would normally be a down day does not pose much risk.

If Yamamoto did that once during a regular season, and then kept his normal routine, he would not have spiked his ACWR above our redline of 20% as we can see in the chart above.

In other words, what Yamamoto did in Game 7 was not inherently dangerous. He had built up the capacity for such additional, emergency work.

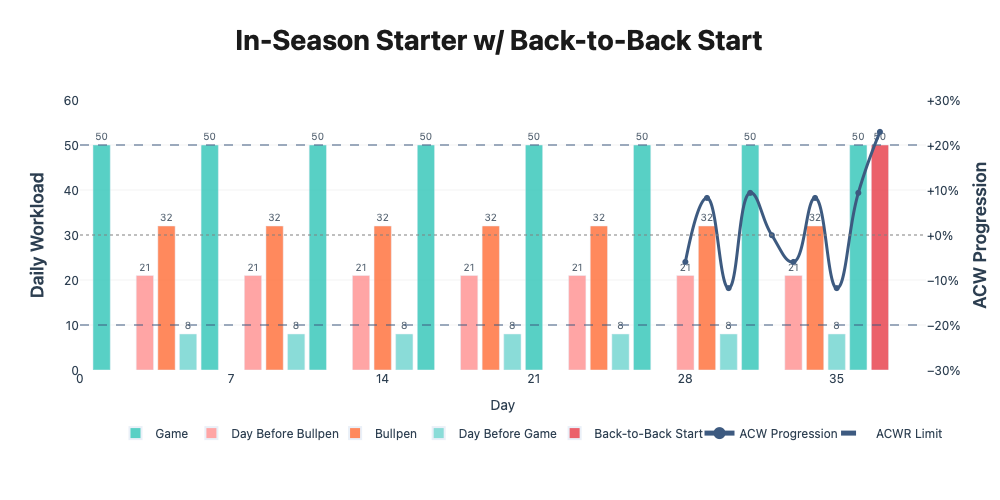

To cross a redline, to spike his ACWR by more than 20%, he would have had to reach 50 workload units in Game 7. In other words, he would have to throw full game-day workloads, 100-plus pitches, on back-to-back days.

How far would Roberts have pushed Yamamoto on Game 7? We will never know as the game ended in 11 innings.

Roberts said he was not going to be tied by a pitch count in Game 7 regarding Yamamoto, rather, the eye test.

“I think that there’s a mind component. There’s the delivery, which is a flawless delivery, and there’s just an unwavering will,” said Roberts to reporters afterward of his decision letting Yamamoto pitch. “You know, all that combined. And there’s certain players that want moments, and there’s certain players that want it for the right reasons. But Yoshi is a guy that I just completely implicitly trust, and he’s made me a pretty dang good manager.”

We will never know how long Roberts would have stuck it out with Yamamoto, but it would have been fascinating to see him return to the mound for a 12th, or a 13th, 14th or even a 15th inning.

The workload data says Roberts could have kept pushing Yamamoto if he needed to.

So did Yamamoto’s real-time stuff.

Remarkably, Yamamoto did not lose any throwing velocity. In fact, he threw with his greatest average fastball velocity of the postseason in Game 7 (96.7 mph).

He allowed one hit, one walk, and struck out one over 2 2/3 scoreless innings .

Even Yamamoto was surprised by how well he performed, perhaps speaking to the power of using ACWR as a guide.

Said Yamamoto to reporters afterward via his interpreter. “When I started in the bullpen before I went in, to be honest, I was not really sure if I could pitch up there to my best ability … But as I started getting warmed up, because I started making a little bit of an adjustment, and then I started thinking I can go in and do my job.”

So long as it’s just a one-time, or rare spike in usage, Hejka does not believe it places the pitcher at extreme risk.

“If he started Game 5 and then came in relief in Game 6 and 7, it’s like, OK, that seems (extreme). But even then, it’s hard. It’s hard to cross that line in a single series,” Hejka said.

Another way to think about this concept would be a pitch count spike in season.

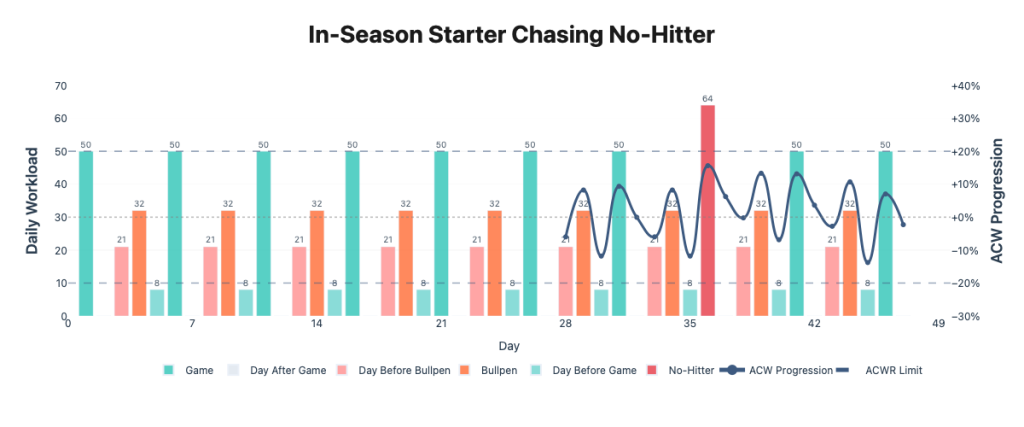

What would it mean for his ACWR if Yamamoto was, say, chasing a no-hitter in August, and Roberts let him reach a Nolan Ryan-like workload of 64 units, or, 155 pitches?

If a starter slightly curtails his workload within his following outing – moving from 14 workload units above expectation in the no-hit bid to six units below in his next start in our simulation – he remains in a healthy ACWR position.

Again, the data suggests a pitcher who has built up their chronic workload capacity can withstand such a spike.

Engelbrekt noted Yamamoto’s World Series case is different than trying to build a Ryan-like workload.

Engelbrekt said while both cases require “a properly managed workload” guided by ACWR, the one-time case of Yamamoto is not as “crazy” as an attempt to build a Ryan-like workload.

Still, each such case requires risk tolerance in straying away from conventional practices.

Coaches and players have varying degrees of risk related to workload, Engelbrekt said. There was perhaps less risk for Yamamoto in venturing into the unknown as Engelbrekt noted “he basically has a lifetime contract.” Yamamoto has generational, guaranteed wealth with his $325-million deal.

But perhaps a takeaway from Yamamoto’s World Series performance is that managers can push their best arms when necessary. They don’t always have to be so conservative. Pitchers can be built for such a moment. They can be prepared by being over prepared and see benefits like improved quality of stuff.

Managers should perhaps be more willing to allow pitchers to take on even greater workload in the postseason and when chasing history in the regular season – those no-hitters bids. The data says it’s reasonable safe, and that would be the far more entertaining option.

The Pirates probably didn’t to pull Paul Skenes when the then rookie had no-hitter through seven innings, having tossed 99 pitches, in 2024. Skenes is a pitcher intent on building workload to Ryan-like levels.

Engelbrekt and Hejka note the Yamamoto case is similar to when there is handwringing over a college ace posting a big pitch count number in an NCAA tournament game.

“Coaches sometimes have a guy rip 150 pitches in a College World Series game,” Hejka said, “doing that once or twice in the Regionals and World Series, it’s less of a risk than doing it every week for 162 games.”

Perhaps the lesson is this: when a manager needs to break glass in case of emergency, like in Game 7 of the World Series, they ought not to be afraid of crossing red lines.

They should know – confidence buoyed by ACWR data – a pitcher like Yamamoto is built to withstand such a one-time ask; he’s built himself to be capable of a legendary performance.

Comment section