Youth Injury Series: Osgood-Schlatter’s and Sever’s Disease

In previous posts, we have examined growth-plate injuries and their effects on the shoulder and elbow. Similarly, in the lower extremity, overuse injuries also happen at the knee and heel. In the arm, these injuries occur at areas with the majority of bony growth. In the leg, they occur at the apophysis, a secondary area of bony growth where the bone grows outwards and has minimal effect on the length of the bone. The apophysis is also an area of tendon or ligament attachment. As a result, this area experiences shearing forces from the pull of these tissues which, over time, can become irritated. This inflammatory response is known as apophysitis. Apophysitis at the knee is called Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease; at the heel, Sever’s Disease. With both, early detection and proper management is essential to limiting the effects it can have on athletes’ playing time.

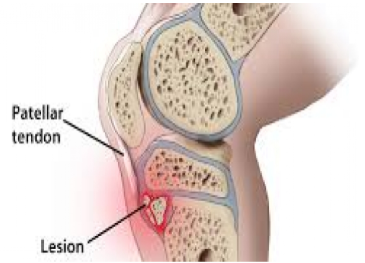

Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease is the more common of the two in the lower extremities. and has been reported to occur in 13-17% of youth athletes. In females, symptoms most often appear between the ages of 8 and 13. In males, they can appear generally between the ages of 10 and 15. At the knee, the patellar tendon, or the end of the quadriceps muscle, attaches beneath the patella onto the bony prominence of the front of the tibia, known as the tibial tuberosity. When the quadriceps contracts, traction forces are placed on the tuberosity. At certain times in the maturation process, the tibial tuberosity is weaker and unable to withstand these forces as efficiently as with older athletes. As a result, small fractures can occur and be deposited further down the tuberosity—where they solidify. Eventually, this area enlarges and can become very painful and sensitive.

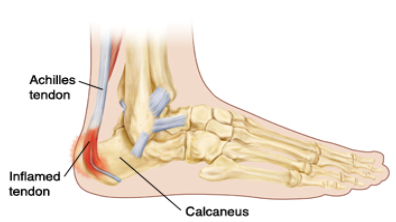

Sever’s Disease, which takes place at the achilles attachment of the heel, has been reported to occur in 2% to 16% of athletes. Generally, Sever’s most often occurs between the ages of 9 and 12. The mechanism is similar to Osgood-Schlatter’s, in which the traction forces of the achilles become too stressful for the calcaneus, the bone where the achilles attaches. As a result, small fractures occur that lead to a bony enlargement of the back of the heel. This area can also become painful and sensitive.

Both conditions share similar causes and predisposing factors. Weakness and poor stability in the lower extremities are major contributing factors: not just around the knee or ankle, but also the hips, glutes, and trunk musculature. In addition, poor flexibility in the ankle, hamstring, and quadriceps, may also add to the amount of stress placed on the knee and heel. It has also been reported that athletes with a higher body-mass index (BMI) may also be at risk for developing this type of injury due to the increased stresses placed on tendons and ligaments. Finally, correlations have been drawn to poor foot positioning—namely a pronated, or flat arch shape—predisposing youth athletes to injuries to the lower extremities. Generally, this foot position puts more stresses on the ankles, knee, and hips, increasing the demands of the muscles that attach to these areas.

If left unchecked for a long enough period of time, these conditions can become so painful that rest from sport may be necessary. Many studies recommend athletes taking anywhere from 4 to 6 weeks—or in severe cases, 3 to 5 months—off from their sport to allow symptoms to subside. During this time, doctors will likely recommend physical therapy to improve flexibility, lower body strength, balance, and overall motor control. Orthotics may also be recommended for athletes with flat foot structure to help improve body mechanics when returning to their sport. Eventually, as symptoms diminish, the doctor or physical therapist will guide a gradual return-to-play schedule for athletes to ensure they do not get start their sport again too quickly.

While not completely preventable, the likelihood of developing Osgood-Schlatter’s or Sever’s disease can be significantly decreased with proper management of youth athletes. Limiting overexposure to training or sport participation is one of the most important things to do. While there is no set limit as to how much youth athletes should play, various studies have recommended that an individual’s workload, whether time spent playing or intensity of training, should not be increased by more than 10% each week. Furthermore, often preceding an injury, an athlete will demonstrate signs of fatigue or decreased playing performance. Coaches or parents should be responsible for recognizing when athletes may be demonstrating these signs and modify their workload accordingly. For coaches, it is also important to recognize that youth athletes mature at different rates. As a result, the same amount of training or activity may be no problem for some, but may be beyond what other players can tolerate. Again, constant monitoring of each athlete is key to limiting the likelihood of injury.

Apophyseal injuries in the lower extremities remain one of the most prevalent injuries in the youth athletes across all sports. Overtraining, poor strength, and decreased flexibility remain among the biggest contributors. Proper workload management, along with a supervised strength and conditioning program, can play a vital role in significantly reducing the risk of youth athletes having to miss significant time from the sports they love.

This article was written by our in-house physical therapist Terry Phillips

References:

Arnold, Amanda, et al. “Overuse Physeal Injuries in Youth Athletes.” Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, vol. 9, no. 2, 6 Feb. 2017, pp. 139–147., doi:10.1177/1941738117690847.

Launay, F. “Sports-Related Overuse Injuries in Children.” Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, vol. 101, no. 1, 2015, doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.030.

Longo, Umile Giuseppe, et al. “Apophyseal Injuries in Children’s and Youth Sports.” British Medical Bulletin, vol. 120, no. 1, 2016, pp. 139–159., doi:10.1093/bmb/ldw041.

Nakase, Junsuke, et al. “Precise Risk Factors for Osgood–Schlatter Disease.” SpringerLink, Springer, Dordrecht, 2 July 2015, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00402-015-2270-2.

Smith, James M. “Sever Disease.” Advances in Pediatrics., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 17 June 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441928/.

Comment section